Merchants of Venice: Daily Life and Urban Movement, ca. 1740

Introduction

Motivation

Large-scale historical narratives often privilege major events, institutions, and prominent actors, while the everyday lives of ordinary people remain difficult to observe. Yet it is precisely these daily routines—opening a shop, crossing a bridge, visiting a tavern or a church—that constitute the lived fabric of a city. Understanding this Alltag, the texture of everyday life, is essential for grasping how historical cities functioned in practice.

In cities like Venice, urban life was shaped by spatial constraints, proximity, and repeated movements through a dense network of streets and canals. Archival sources such as tax registers capture static snapshots of ownership and location, but they provide little insight into how people actually moved through space or structured their days. As a result, patterns of routine mobility, local interaction, and spatial habit remain largely implicit.

Recent work in digital humanities and agent-based modeling has shown that simulations can help explore such questions by shifting attention from static records to dynamic processes. By modeling how individuals might have used urban space on a daily basis, these approaches offer a way to investigate historical plausibility and emergent spatial patterns that are otherwise difficult to infer directly from documents.

Research Aim and Contribution

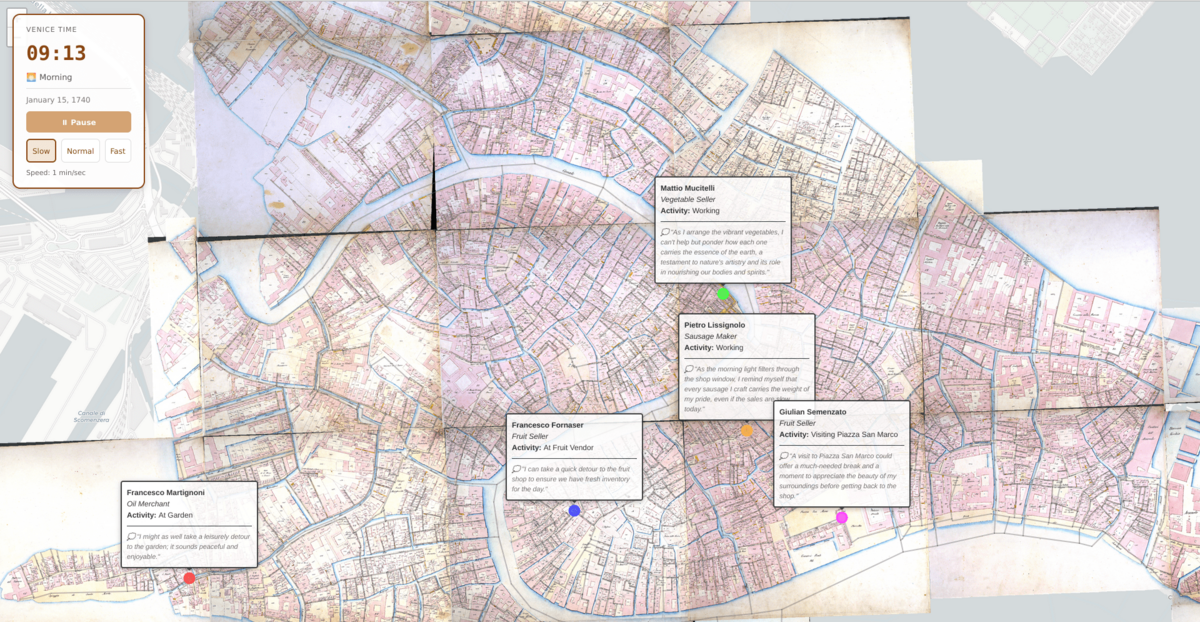

This project explores how the everyday life of Venetian merchants around 1740 can be plausibly modeled using an agent-based simulation grounded in historical data. Rather than reconstructing specific historical individuals, the aim is to investigate how daily routines, spatial constraints, and local opportunities shape patterns of movement and activity within the city.

To this end, we combine archival data from the 1740 Catastici with a historical street network and an agent-based simulation framework. Merchants are modeled as autonomous agents who follow time-based routines, navigate the urban network, and occasionally engage in spontaneous actions. Generative AI is used in a constrained manner to enrich sparse data by producing short internal thoughts and selecting among predefined options for detours, without granting agents unrestricted autonomy.

The main contribution of this project is methodological. It demonstrates how archival sources, spatial modeling, and generative tools can be integrated into a coherent simulation that foregrounds everyday urban life. The project does not claim historical accuracy at the individual level, but instead offers an exploratory framework for thinking about plausibility, routine, and movement in a historical city.

Project Timeline and Milestones

This project is structured in two main parts: Data (Sampling and Generation) and Agent (Behavior) part. Work on both tracks runs in parallel. As the data generation improves, its outputs are continuously integrated into the agents' routines and behaviors. The process is iterative: refine the data, update the behavior, and progressively converge toward a coherent simulation of daily life

| Category | Task | Start | End |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling & Generation | Analyze dataset | Nov 11 | Nov 17 |

| Sampling & Generation | Build merchant dataset | Nov 17 | Nov 24 |

| Sampling & Generation | Persona & routine draft | Nov 17 | Nov 24 |

| Sampling & Generation | Data sampling | Nov 17 | Nov 24 |

| Sampling & Generation | Persona/routine refinement | Nov 24 | Dec 1 |

| Other | Wiki writing | Dec 8 | Dec 15 |

| Other | Polishing and testing | Dec 8 | Dec 15 |

| Category | Task | Start | End |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior | Build agent architecture | Nov 11 | Nov 20 |

| Behavior | Integrate time-synced logic | Nov 14 | Nov 24 |

| Behavior | Integrate persona/routine prompt | Nov 24 | Dec 8 |

| Behavior | Agent thought display | Nov 24 | Dec 1 |

| Behavior | Multi agent | Dec 1 | Dec 8 |

Deviations from timeline

While the initial plan defined a clear separation between data preparation and agent behavior, the project required more extensive data analysis than originally anticipated. Cleaning, filtering, and interpreting the Catastici proved to be more complex, particularly when resolving ambiguities in identities and functions.

In addition, spontaneous agent detours were introduced during development. This required the creation of a dedicated POI dataset, extending the original scope but significantly improving the realism of agents’ daily movements.

Milestones

| Milestone | Date |

|---|---|

| First working prototype, 1 agent which moves based on routine | 23.11 |

| Agent thinks | 01.12 |

| Spontaneous actions | 04.12 |

| Multi-agent system | 11.12 |

| Final deadline | 17.12 |

Final deliverables: 17.12 GitHub + Wiki

Final presentation: 18.12

Deliverables

- Jupyter notebook with data exploration and analysis to make informed data processing decision.

- Python scripts for data processing and dataset creation of the following: merchants personas and point of interests.

- Next.js web application that renders Venice’s navigable network and animates agents over time, providing an accessible interface for testing and presentation

- FastAPI backend that provides LLM-backed endpoints for generating “thoughts” and constrained detour decisions.

Data & Assumptions

Data Sources

Street network (1808)

To represent Venice as a navigable environment, we rely on the 1808 Venetian street network. While our agents are situated around 1740, we assume that the city’s urban fabric remained sufficiently stable between 1740 and 1808 for this network to serve as a reasonable proxy. The raw network contains gaps and inconsistencies introduced during the original acquisition process.

A previous FDH group ([1]) addressed these issues and produced an improved version of the network through a combination of automated and manual corrections. They also integrated traghetti crossings, which allow pedestrians to traverse the Grand Canal at key points and are essential for everyday mobility. We use this enhanced network, which includes both walkable paths and traghetti routes, as the spatial foundation for movement in the simulation.

Catastici (1740)

Our primary archival source is the 1740 tax register (Catastici). The register records a large number of parcels and tenants, but only a subset is useful for modeling merchant activity. In particular, we exclude shops without a specified shop type, since generic labels such as “Bottega” provide no information about occupation and add noise to the sample.

From the original 31,741 rows, we identify 23,899 unique tenants. Among them, 3,040 normalized names occur more than once, indicating multiple associated parcels (for example, several houses, or a house combined with one or more shops). Within this group, 968 tenant names have at least one shop associated with a meaningful shop type. This subset forms the basis of our merchant sample; however, because tenant names are not unique identifiers, a single name may correspond to multiple historical individuals. As a result, the final number of simulated merchants after identity disambiguation is not constrained by the number of unique names and may be higher.

A key challenge in the Catastici is homonymy: individuals who share the same given name and surname are not distinguishable by a unique identifier. As a result, multiple distinct people can be merged into a single entity if they share a name. For example, “Antonio Rossi” appears across 23 parcels associated with several distinct functions (surgeon, barber, tailor, as well as multiple houses), which is implausible as a single life. This motivates a later identity-resolution step in the data pipeline (described in the Methods section).

During the data exploration, we also found an external reference to an Antonio Rossi, identified as a Venetian surgeon [2]. This is a compiled volume of scholarly pamphlets, where the skeleton in his study is mentioned, published in 1732. While this does not resolve our homonymy issue, it confirms that at least one historical Antonio Rossi did practice surgery in Venice, and that we have a trace of it.

Assumptions

This project aims for plausibility rather than reconstruction. The simulation therefore relies on explicit modeling assumptions that define what the agents can and cannot do, and what kinds of claims the system supports.

Urban continuity (1740–1808): We assume the overall structure of Venice’s walkable network remained stable enough for the 1808 network to approximate mobility constraints in 1740.

Network accessibility: All agents can traverse all edges of the network. Traghetti crossings are treated as traversable routes, and no restrictions are modeled (e.g., pricing, social access, or congestion).

Uniform movement model: Movement is approximated using a constant walking speed (1.4 m/s, approximately 5 km/h) to estimate travel times.

Discrete time model: The simulation advances in discrete time steps. Agents’ routines and decisions are updated according to this shared simulation clock.

Identity scope: Because the Catastici do not provide unique identifiers, “agents” represent plausible historical individuals constructed from the register, rather than verifiable persons. Identity disambiguation is treated as a data-processing problem addressed in the pipeline.

Sampling Scope

The simulation focuses on individuals whose occupation can be inferred from the Catastici. Throughout this report, we use the term "merchant" in a broad sense to designate anyone operating a bottega (shop) with an explicit shop type—this includes not only traders and sellers, but also artisans, service providers, and craftspeople such as bakers (forner), barbers (barbier), tailors (sartor), surgeons, and many others.

This inclusive definition reflects a methodological constraint: the Catastici records building functions and shop types, but does not explicitly document occupations or professions. The only systematic way to infer daily economic activity is through the presence of a shop with a specified type. Consequently, we exclude generic or uninformative labels (e.g., "Bottega" without further qualification), as they provide no basis for modeling occupation-based routines.

Data Exploration

We built the simulation datasets by cleaning and transforming the raw Catastici, guided by an exploratory analysis. The patterns identified in this process serve two roles: they confirm that the filtered register reflects meaningful economic activity, and they inform modeling choices such as occupation-conditioned personas and a POI-based detour mechanism.

Owners and tenants

The Catastici distinguishes between owners (proprietari) and tenants (conduttori), which makes it possible to observe how property ownership relates to everyday economic activity. A notable pattern is the prominence of religious and charitable institutions among the most frequent owners. However, the parcels they own are not exclusively religious in function: institutional owners frequently appear as landlords of houses (casa), shops (bottega), and mixed-use properties. This suggests that ecclesiastical and confraternal actors were structurally embedded in Venice’s urban rental economy rather than being confined to strictly religious property.

To illustrate this, Figure 1 lists the most common owners in our filtered dataset. While the ranking reflects the specific subset used for our analysis, it highlights the institutional concentration of ownership and motivates treating “ownership” and “economic activity” as distinct layers: daily life is primarily modeled through tenants and shop functions, while ownership provides contextual evidence about the broader urban economy.

Shop types

To ground agent personas and routines in historically attested economic activity, we first examined the distribution of shop types recorded in the Catastici (Figure 2). The most frequent categories correspond to everyday consumption and services—food provisioning, clothing, and personal trades—which suggests that much of merchant activity was structured around regular, local demand rather than rare or exceptional events. This supports modeling merchants with stable daily routines centered on a small number of anchor locations (home and shop), with repeated short-range movements.

At the same time, the presence of jewellery among the most common shop types indicates that valuable and portable goods were not marginal in Venice’s urban economy. While the register does not reveal transaction volumes or social clientele, this reinforces the idea that Venice combined everyday provisioning with forms of trade linked to credit, resale, and the circulation of wealth.

Point of Interest

The following maps present the spatial distribution of key points of interest in Venice around 1740, focusing on economic activity, sociability, and institutions. Rather than showing all functions at once, each map isolates a specific aspect of urban life in order to make underlying spatial patterns visible.

Economic buildings

As shown on the map, Venice in 1740 was an economic city shaped by water.

Most points of interest are located directly along canals, especially the Canal Grande and its secondary branches. This shows that movement and access by boat were more important than movement through streets.

The Rialto area clearly appears as the main economic center of the city, with a high concentration of shops, storage spaces, and financial activity. At the same time, the outer areas of the city are not empty: commercial activity is less dense but still present throughout Venice.

This means that economic life was spread across the city. Everyday goods and services were available close to where people lived, and inhabitants did not always need to travel to Rialto for basic purchases.

Social buildings

This map shows that places of leisure and sociability follow different spatial patterns.

Taverns and inns are mostly located in central and well-connected areas, especially along major canals and near the Rialto. These places benefit from movement, trade, and a steady flow of people, including merchants and travelers.

Casinos, on the other hand, appear more often in peripheral or less central areas. This suggests that they were more secluded and less visible, fitting their semi-private character and their role as exclusive social spaces rather than everyday meeting places.

Theaters and larger lodging places are few and located in specific, strategic locations, showing that these activities required visibility and access to a wider public.

Administrative buildings

Churches and confraternities are spread across the whole city. Almost every area has nearby religious or charitable institutions, showing how deeply they were embedded in everyday life. These places structured neighborhoods and daily rhythms.

Hospices are fewer and more unevenly distributed, reflecting their specific charitable function rather than everyday use. Post offices are rare and centralized.

Taken together, these maps show Venice as a dense and highly mixed city, where everyday economic and social activities were spread across the urban fabric, while certain functions remained more concentrated. Trade and work were closely tied to canals, sociability followed both central routes and local neighborhoods, and institutions such as churches and confraternities structured daily life at a local scale. This spatial organization supports modeling Venetian inhabitants as locally embedded agents, whose routines unfold within a city shaped by water, proximity, and repeated interactions.

Note on usage in the simulation: The maps above describe the functional landscape of the Catastici-derived POI layer, but the current simulation does not operationalize the full typology. In practice, we curate a subset of “interesting” POI categories for spontaneous detours (e.g., hospitality, religious institutions, selected civic functions) and we include specialized shop types when available. Many other recorded functions are therefore visible in the descriptive analysis but are not currently used as destinations or constraints in the agent model. This gap is addressed explicitly in Future Works.

Methods

Data Pipeline

The data pipeline translates the raw Catastici register into structured datasets that can be consumed by the agent-based simulation. It consists of two parallel branches: one focused on constructing historically plausible merchant identities and routines, and one focused on extracting points of interest used for spontaneous actions. Figure 3 summarizes this pipeline and situates each processing step described below.

Identity Resolution

After cleaning and filtering the dataset (Figure 3, upper branch, build_merchant_dataset.py), we still face homonymy, as described in the Data & Assumptions section.

To cluster shops with their corresponding houses, and to disentangle different individuals who share the same name, we use a graph-based thresholding approach. Each node represents a single Catastici entry. We add edges between nodes that share the same tenant name, then assign weights using a custom scoring function. After constructing the graph, we apply connected-components thresholding to retain only the clusters whose internal similarity exceeds a defined score.

The scoring function incorporates several factors:

- Parish

- Sestiere

- Geographical distance between parcels

- Parcel type (house vs shop)

- Shop subtype when applicable

Applied to the case of Antonio Rossi, this method yields three distinct clusters: one associated with a barber activity, one with a surgeon’s shop, and one grouping the tailor shops, effectively separating homonymous merchants into plausible historical identities.

Following identity resolution (Figure 3), we aggregate the resulting clusters into a merchant dataset containing all simulated agents (1024 entries). This number exceeds the count of unique tenant names with informative shop types (968) because the identity-resolution process splits homonymous names into multiple plausible individuals when supported by spatial and functional evidence.

Persona and Routine Generation

As shown in Figure 3, the cleaned merchant dataset is then passed to a generative step that enriches each merchant with a short persona and a time-based daily routine. In generate_personas.py, we make API calls to GPT-4o to generate personality traits and a daily routine based on the merchant's name, inferred occupation, and home and shop locations.

Addressing LLM Bias Through Archetype Sampling

Initial experiments revealed a significant limitation: without explicit guidance, GPT-4o consistently generated merchants with near-identical personalities—typically devout, meticulous, and business-focused. This homogeneity indicates a limited range of personality expression in the generated thoughts. Although the archival sources do not document individual dispositions, it is reasonable to expect diversity among historical actors; the observed convergence therefore reflects the language model’s internal priors rather than evidence derived from the data.

To address this, we developed a two-stage approach:

- Archetype Generation: We first used GPT-4o to generate 15 distinct personality archetypes grounded in 18th-century Venetian social structures (e.g., "Deeply pious and devout," "Shrewd and calculating," "Carefree and lazy," "Status-seeking")

- Archetype-Guided Generation: Each persona generation randomly selects one archetype and explicitly instructs the model to "follow this exactly," ensuring personality diversity while maintaining historical plausibility

This design choice transforms the LLM from generating personalities freely to interpreting and elaborating on predefined archetypes—a form of constrained generation that produces both variety and consistency. The system uses a high temperature (0.9) to encourage creative elaboration within each archetype's constraints.

Output Structure

The process results in personas.json, containing for each merchant:

- Name and occupation (e.g., "Agostin Cigaggia - Cheesemonger")

- Personality traits (1-2 sentence profile following the assigned archetype)

- Home and shop locations (WGS84 lat/lng coordinates converted from UTM Zone 33N)

- Daily routine blocks with time ranges (HH:MM format) and activity labels

The routine generation follows strict constraints: activities must span 05:00-22:00, use 30-60 minute granularity, and employ exactly five activity types (HOME, SHOP, FREE_TIME, TRAVEL_TO_SHOP, TRAVEL_HOME). Consecutive activities of the same type are automatically merged to prevent fragmentation. The semantics of these labels are defined by the simulation model and described in the Agent-Based Simulation section.

Points of Interest Dataset Construction

In parallel to merchant processing (Figure 3, lower branch), we construct a POI dataset from the Catastici to support agents’ spontaneous actions. Because the full register contains many parcel types that are not useful as destinations, we apply a two-stage filter.

First, we exclude non-destination top-level functions (e.g., CASA and INVIAMENTO) and remove generic shop entries without a specialized shop type. Second, we retain (i) any entry with a specialized shop label (PP_Bottega_STD), and (ii) entries whose mid-level function tokens (PP_Function_MID) match a curated whitelist of “interesting” categories used by the simulation (e.g., OSTERIA, LOCANDA, CHIESA, SCUOLA, GIARDINO, CORTE, ORTO, TEATRO, CASINO, FONDACO, BANCO, POSTA, OSPIZIO, FORNO, PISTORIA).

Each POI includes:

- Unique identifier

- Coordinates (lat/lng)

- Type (period-appropriate Italian terms)

- Human-readable label (e.g., "Santa Maria della Salute")

The POI dataset includes 3536 points of interest distributed across the city of Venice. At runtime, agents query only a local subset of POIs (described in the Spontaneous actions section) to keep decision contexts small and reachable.

In addition to Catastici-derived POIs, we manually added a small number of well-known Venetian landmarks (e.g., Rialto Bridge, Piazza San Marco, the Arsenal) that are not reliably encoded as visitable destinations in the register but play a central role in the city’s spatial and symbolic life. These landmarks were handpicked and inserted directly into the POI dataset to support realistic detours and orientation behavior. They are explicitly marked as landmarks and treated separately from Catastici-based POIs in the simulation.

Agent-Based Simulation

This section describes the computational methods used to operationalize the processed historical data into an agent-based simulation.

Architecture Overview

The simulation is split between a Next.js frontend that runs the deterministic simulation loop (state updates, movement, pathfinding) and a FastAPI backend that provides LLM-backed endpoints for thought generation and constrained detour choices. Figure 4 summarizes these responsibilities and the runtime data flow between components.

Frontend

Agents are initialized from the curated dataset personas.json (produced by the data pipeline) and use the POI dataset for detour decisions. The frontend uses a React-based architecture with TypeScript that manages agent state (position, path, routine, mode), movement simulation along paths, routine scheduling based on time of day, detour feasibility checking and execution, and rendering and animation of agents over the Venice network. The system determines the current activity based on simulation time, handling edge cases like midnight-spanning routines (e.g., routines that start at 23:00 and end at 02:00). Agents automatically transition between activities and compute new paths when their routine changes.

Backend

The simulation uses a FastAPI backend that serves as the LLM interface for agent decision-making, using OpenAI GPT-4o-mini for an effective balance between speed and output quality. The backend provides two capabilities: generating first-person inner thoughts for agents based on their current context, and making constrained decisions about which spontaneous activity to pursue based on agent personality and a small set of reachable options.

Time Model and Simulation Speed

The simulation operates on a compressed time scale to allow observation of full daily routines within reasonable real-world durations.

Simulation Time:

- The simulation tracks a virtual clock representing time in 1740 Venice (hours and minutes)

- This clock can be started, paused, and reset by the user

- All agent routines, detour timing, and dwell durations are expressed in simulation minutes

Time Compression:

- Real-world seconds are multiplied by a configurable time speed factor

- Default: 1 real-world second = 5 simulation minutes

- This means a full 24-hour Venetian day unfolds in approximately 4.8 real-world minutes

- The time speed can be adjusted to allow faster observation or more detailed inspection

Movement Synchronization:

- Agent movement along paths is synchronized with simulation time

- Walking speed (1.4 m/s) is scaled by the time factor to maintain realistic spatial relationships

- All agents advance through their paths simultaneously with each simulation tick

This time compression allows users to observe multiple routine cycles, detour decisions, and daily patterns within a single viewing session, while maintaining internal consistency in agent behavior and spatial constraints.

Agent Capabilities

Routine Model

Agents follow time-based routine blocks generated in personas.json. The simulation interprets these blocks through a small set of routine labels that map to stationary or travel behaviors:

- HOME - Agent stays at home

- SHOP - Agent works at their shop

- TRAVEL_TO_SHOP - Agent commutes to shop

- TRAVEL_HOME - Agent commutes home

- FREE_TIME - Agent is free to detour or stay at current location

These labels provide a simple interface between generated routine blocks (pipeline output) and deterministic movement/decision logic (simulation runtime).

Pathfinding

Network Structure: The navigation network is built from a 1808 Venice GeoJSON dataset containing historical street and canal routes.

- Nodes represent coordinates (lat/lng pairs)

- Edges connect consecutive coordinates along streets and canals

- Traghetti (gondola ferry routes) are integrated into the network as traversable edges

Pathfinding Algorithm: The system uses Breadth-First Search (BFS) for pathfinding:

- Unweighted graph traversal (all edges treated equally)

- Guarantees shortest path in terms of number of nodes

- Efficient for the dense urban network of Venice

All edges are treated as equal-cost, and travel time is estimated using the uniform walking speed defined in the Assumptions section.

Thought Generation

Agents generate short first-person inner thoughts that reflect their personality and current situation. When a thought is needed, the frontend requests it through the backend. The backend receives:

- Agent name and personality

- Current activity and location

- Time of day

- Optional context (e.g., detour information)

The system prompt instructs the LLM to:

- Think in first person as the character

- Stay concise (1-2 sentences)

- Avoid proposing explicit actions or plans

- Focus on internal reflection and authentic period voice

Example Thoughts: Agostin Cigaggia (Cheesemonger) at his shop in the morning:

"The morning barge should arrive soon with fresh ricotta—I must check the aging wheels before the midday rush begins."

During a detour to a tavern:

"A brief respite at the osteria will do no harm; I can hear word of the terraferma harvest while sampling their wine."

At a church during free time:

"I take a quiet moment to register where I am and the time of day."

Autonomous Detours

Agents can override their routines autonomously, creating a more dynamic and realistic simulation where they make spontaneous decisions based on their personality and available time. Detours rely on the POI dataset produced by the data pipeline. Importantly, agents do not consider all POIs in the city at once—they only see a small set of nearby, reachable options to keep decisions plausible and the LLM context manageable.

Context-Aware POI Fetching: The system fetches POIs within a 15-minute walking radius of the agent's current position using a distance-limited graph traversal. This ensures:

- The LLM context remains manageable (typically 1-4 options)

- Detour options are realistically reachable

- Agents only see locations they could visit within their time constraints

Detour Decision Logic:

Timing Constraints:

- Periodic checks: Only evaluated every 15 simulation minutes to reduce API calls

- Cooldown period: 60-minute cooldown between detours per agent

- Daily cap: Maximum 2 detours per day per agent

- Minimum slack: Requires at least 45 minutes of available time before next obligation

- Safety buffer: An additional 5-minute buffer is added to ensure timely arrival at next obligation

- Activity restrictions: Agents cannot detour while traveling (TRAVEL_TO_SHOP, TRAVEL_HOME), only during stationary routines (HOME, SHOP, FREE_TIME)

Feasibility Calculation:

For each potential POI, the system calculates:

totalTimeNeeded = travelToPoiMinutes + dwellMinutes + returnToTargetMinutes

detourIsFeasible = (totalTimeNeeded + 5) <= availableSlackTime

Only POIs that fit within the available slack time (with a 5-minute safety buffer) are presented as options.

POI Type Diversity with Randomization: To provide interesting and varied choices across multiple agents, the system:

- Categorizes nearby POIs into four groups (Hospitality, Religious, Outdoor, Landmarks)

- Randomly selects up to 2 POIs from each available category (instead of always picking the same closest ones)

- Includes a fallback random selection if no categorized options exist

- Presents up to 4 diverse options plus a "none" option

Dwell Time Estimation: Different POI types have different estimated dwell times based on realistic visit durations:

- Taverns/Social venues: 20-35 minutes

- Churches/Religious buildings: 10-20 minutes

- Gardens/Courtyards: 15-30 minutes

- Landmarks: 20-40 minutes

- Default: 15-25 minutes

The actual dwell time is randomized within these ranges and capped at 70% of available slack time to ensure proper time management. Dwell time is calculated from arrival at the POI, not from departure, ensuring agents spend the full intended time at each location.

LLM Decision Process: When a detour opportunity arises, the backend sends the LLM:

- Agent personality and name

- Current time of day (in 24-hour format)

- Main goal with deadline (e.g., "Be back at your shop by 13:30")

- Available time before next obligation (in minutes)

- List of up to 4 reachable POI options (plus "none")

The LLM responds with structured JSON containing:

choice_id: The selected option identifier or "none"thought: Optional first-person rationale for the decision

The system validates that the LLM only chooses from the provided options and handles parsing failures gracefully by defaulting to "none". Agents transition through three modes during detours (ROUTINE → DETOURING → AT_DETOUR → ROUTINE), and the system provides enhanced activity descriptions using POI metadata, displaying full landmark names or translating Italian POI types to English.

Multi-Agent Orchestration

The simulation supports multiple autonomous agents operating concurrently in the same Venice environment. Each agent runs independently with its own state, personality, routines, and decision-making, while all agents share the same simulation clock and physical environment.

Scaling Challenge

Running multiple autonomous agents simultaneously created performance challenges:

- Initial approach: GPT-4 for all thoughts

- Too slow for real-time simulation with multiple agents

- Multiple agents requesting thoughts simultaneously caused UI freezing

- Solution: Switched to GPT-4o-mini

- 2-3x faster response times (~1 second per thought)

- Reduced cost per call

- Enabled smooth multi-agent simulation with parallel requests

The system supports multiple simultaneous agents (tested with up to 5, configurable via start-dev.sh) without performance degradation.

Concurrent Agent Management

The system manages multiple agents with:

- Independent state: Each agent maintains separate position, path, routine, and detour state tracked in maps keyed by agent ID

- Shared resources: All agents use the same network graph and POI dataset

- Synchronous time: All agents update simultaneously with each simulation clock tick

- Asynchronous decisions: Detour decisions and thought generation happen independently per agent without blocking other agents

- Request deduplication: Per-agent locking prevents duplicate API calls if a decision is still pending

- Collision-free movement: Agents do not interact or collide with each other

Results

This section reports what is observable when running the interactive simulation over multiple trials (dozens of runs). It focuses on trajectory patterns, the practical effect of detours, and how multi-agent simultaneity reads at the city scale, without claiming individual-level historical validation.

Routine anchors and neighborhood-scale mobility

Across runs, agents display strongly localized daily mobility structured around home and shop anchors. This is grounded in the data: about 55% of merchants live at the same location as their shop, and many of the remaining cases are separated by short walking distances. Consequently, most trajectories consist of short commutes and repeated local circulation rather than city-wide traversal.

This locality is not primarily explained by the identity disambiguation step. The merchant sample starts from 968 unique tenant names with informative shop types and increases to 1024 simulated merchant identities after clustering, so the adjustment affects a minority of cases and does not account for the overall prevalence of co-located home/work anchors. The historical street network shapes circulation by channeling agents through specific routes, bridges, and traghetti crossings, producing repeated paths over time.

Detours as bounded variation

Spontaneous actions introduce variation as short, deadline-compatible deviations rather than free roaming. In practice, detour options are generated from the agent's current position (typically near home or near shop), which keeps most detours local. Exceptions mainly occur for a small number of explicitly included landmarks.

Console traces make this visible: for each agent, a small set of nearby options is proposed, feasibility is checked (travel + dwell + return), and the option list includes "none," allowing the agent to continue directly to its obligation. The LLM-based decision incorporates the agent's personality archetype (e.g., pious vs. leisure-seeking), which influences whether and where agents choose to detour. Agents with different personality profiles exhibit distinct patterns in their willingness to deviate from routine and in their preference for certain POI types. At the aggregate level, routines remain dominant, but movement becomes less mechanically repetitive.

Distributed simultaneity in multi-agent runs

With multiple agents (tested up to five), the dominant effect is simultaneity rather than clustering or interaction. Agents remain embedded in their own neighborhoods, yet their synchronized evolution produces a city-wide sense of parallel daily rhythms. The resulting "lived city" impression comes from distributed concurrency across Venice, not from repeated co-presence at shared destinations.

Interpretability through thoughts

Short first-person thoughts add interpretive cues to otherwise similar-looking movements. They help distinguish routine travel from discretionary stops and make detours easier to read as situated actions. In repeated runs, thoughts sometimes drift toward overly poetic or reflective phrasing; this affects narrative tone without changing movement logic.

Pipeline Outputs

Beyond agent behavior, the project produces several structured outputs: a cleaned merchant dataset, a resolved set of plausible merchant identities, a city-wide POI dataset, and generated personas with daily routines. Together, these outputs form a pipeline that transforms static archival records into entities that can be simulated dynamically.

Overall, the system produces localized movement, routine-driven behavior, and limited variability within a historically grounded urban environment, making everyday urban life observable as a process rather than a static record.

Conclusion

Quality assessment

Evaluating the quality of a historical simulation based on fragmented archival data and generative models requires clearly defining what can and cannot be validated. This project does not aim to reconstruct the exact behavior of historical individuals, but rather to explore the feasibility of producing a coherent and plausible model of everyday urban life that remains consistent with known spatial and social constraints of Venice around 1740.

Quality is assessed across five dimensions:

Data Plausibility: Given the absence of unique identifiers in the Catastici, complete historical validation is impossible. Data plausibility was evaluated iteratively during data cleaning and filtering. While no systematic per-entity validation was performed, repeated manual inspection of intermediate outputs and selected individual records provided confidence that the resulting datasets are broadly coherent and suitable for simulation.

Model Coherence: The simulation was assessed for model coherence and technical robustness. Agents follow predefined routines, move exclusively along the historical network, and respect temporal constraints. Randomness is intentionally limited to well-defined components such as detours and thought generation. Performance limitations, mainly linked to LLM usage, are explicitly acknowledged and documented.

Behavioral Credibility: Behavioral credibility is assessed through qualitative observation of exploratory simulation runs. Rather than performing a formal behavioral validation, we inspected movement patterns and selected agent trajectories to identify potential anomalies. While this does not constitute a systematic evaluation, the observed behaviors did not exhibit clear contradictions with known spatial or temporal constraints of Venetian daily life.

LLM Output Characteristics: A consistent stylistic pattern emerges in the LLM-generated thoughts across multiple simulation runs. Agents tend to express themselves as notably pious, meticulous, and morally reflective, with language that is often more verbose and poetic than strictly necessary for the simulated context. References to religious observance, diligence in work, and moral self-assessment appear frequently, even during routine or mundane activities. This stylistic bias reflects the generative model's internal associations with the early modern period rather than information explicitly encoded in the data or prompts. While these thoughts do not affect agent behavior, their tone shapes the qualitative experience of the simulation and highlights how implicit historical priors embedded in the language model surface in narrative outputs.

Transparency and Reproducibility: All data transformations, assumptions, and modeling choices are documented, and the full pipeline is accessible through notebooks and source code.

Limitations

- Data: missing occupations — The 1740 register does not record people's professions. For this reason, we restrict our sample to individuals whose occupation can be inferred from explicit shop types. This biases the sample toward economically active tenants whose daily practices center on a legible workplace, and excludes individuals whose activity is not encoded as a specialized shop type in the register (e.g., landlords, nobles, or workers without dedicated premises). The resulting agents therefore represent a specific subset of 1740 Venice: people whose everyday routines were structured around operating a place of business recorded in the tax register.

- Computing costs — The simulation requires API calls for thought generation and detour decisions, which can become expensive when scaling to many agents or extended runs.

- Language — The data, such as the parcel's function, occupations, are mostly in old Venetian. This made it more difficult to explore it.

- Random sampling — When generating the personas and creating the agents, we sample randomly in the register. However, this will not necessarily lead to a correct proportion of the population.

Future Works

With a solid foundation in place, several extensions could significantly enrich the simulation:

- Weekly-based routines — Generate routines that span an entire week. Merchants could follow different patterns depending on the day (deliveries, market days, religious observance, etc.).

- Broader agent types — Introduce non-merchant populations derived from POIs and institutions, such as priests, porters, gondoliers, postmen, teachers, and others.

- Operationalizing functional POI layers — While the Catastici encode a rich functional landscape (economic, social, administrative, religious), the current simulation uses only a curated subset of POI types for spontaneous detours. Future work could expand this set and explicitly map functional categories to behavioral roles: economic buildings could generate supply-oriented movements (deliveries, sourcing), social buildings could structure leisure and evening activity, and administrative or religious institutions could introduce periodic obligations (church attendance, confraternity visits). This would make the descriptive layers presented in the Data Analysis section actionable within the agent model.

- Sampling based on population details — Sample agents according to an estimated population distribution rather than uniformly at random.

- Historical grounding — Incorporate structured historical knowledge and compare baseline LLM behavior with a RAG system enriched with Venetian sources (guild structures, regulations, work rhythms, etc.).

- Context-dependent movement — Vary walking speed according to activity or urgency; for example, allow agents to move faster when late. Also integrate traghetti costs into the path-finding algorithm.

- Agent interaction — Implement direct interactions between agents, enabling social behavior, information exchange, or simple economic actions.

- LLM memory — Equip agents with a persistent memory layer so decisions accumulate context over time, making behavior more coherent and historically grounded.

References

- 1740 Catastici

- Traghetti in Venice - FDH Project

- Raccolta d'opuscoli scientifici e filologici, Tomo I (1732) - Antonio Rossi reference

Github Repository

Credits

Course: Foundation of Digital Humanities (DH-405), EPFL

Professor: Frédéric Kaplan

Supervisor: Alexander Rusnak

Authors: Camille Lannoye, Sophia Kovalenko