Traghetti in Venice: Difference between revisions

| (32 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

The city of Venice is widely known for its network of canals and its iconic ferries, know as traghetti. While nowadays they mainly serve as a tourist attraction, the traghetti have played a vital role in the daily life of Venetians since the early days of the city, by enabling the movement of both goods and people <ref>ZANELLI, « Gondole et traghetti », p. 60-61.</ref>. By looking at ownership data from a Venetian census of 1740, this study will seek to explore who owned and how the Venetian traghetti were operated during this period. | The city of Venice is widely known for its network of canals and its iconic ferries, know as traghetti. While nowadays they mainly serve as a tourist attraction, the traghetti have played a vital role in the daily life of Venetians since the early days of the city, by enabling the movement of both goods and people <ref>ZANELLI, « Gondole et traghetti », p. 60-61.</ref>. By looking at ownership data from a Venetian census of 1740, this study will seek to explore who owned and how the Venetian traghetti were operated during this period. | ||

This research will focus on three main aspects. First, we will investigate the ownership of the traghetti and try to identify the prominent entities that controlled them. We will then try to understand the motivations behind this ownership, by looking at other business ventures of the entity, its | This research will focus on three main aspects. First, we will investigate the ownership of the traghetti and try to identify the prominent entities that controlled them. We will then try to understand the motivations behind this ownership, by looking at other business ventures of the entity, its layout in the city or other historical motives not necessarily found in the data. | ||

Secondly, we will conduct a spatial analysis in order to explore the distribution of traghetti across Venice. Using the geographical data, we will try to understand the placement of the ferries throughout the city and what kind economic or societal factors determined their position. | Secondly, we will conduct a spatial analysis in order to explore the distribution of traghetti across Venice. Using the geographical data, we will try to understand the placement of the ferries throughout the city and what kind economic or societal factors determined their position. | ||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

* Python scripts production plots and maps for the entity analysis (entity_analysis folder) | * Python scripts production plots and maps for the entity analysis (entity_analysis folder) | ||

* Jupyter Notebooks for matching Catastici and Sommarioni dataset and the results (catastici-to-sommarioni folder) | * Jupyter Notebooks for matching Catastici and Sommarioni dataset and the results (catastici-to-sommarioni folder) | ||

* | * Jupyter Notebooks for mobility analysis(mobility-analysis folder) | ||

==Project Timeline & Milestones== | ==Project Timeline & Milestones== | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

===Milestones=== | ===Milestones=== | ||

Milestone 1 (17.11): Understand what traghetti are and have an idea of what their role is in the city. Provide early visualizations tools for further analysis. Define our research question. | |||

Milestone 2 (01.12): Properly establish the methodology and the tools for the analysis. Finish extracting data and align the datasets. | |||

Milestone 3 (18.12): Finish analysis of the project and write the wiki. The code is clean, annotated and ready to be shared. | |||

==Methodology== | ==Methodology== | ||

| Line 68: | Line 73: | ||

===Data Extraction=== | ===Data Extraction=== | ||

For Catastici dataset, text_data and geojson are exactly the same, except for the geometry column. The difference in geometry column is likely that they adopted difference coordinate systems, and we prefer to use the geojson one for coordinates. Here are the fields we used in the Catastici dataset | For Catastici dataset, ''text_data'' and ''geojson'' are exactly the same, except for the geometry column. The difference in geometry column is likely that they adopted difference coordinate systems, and we prefer to use the ''geojson'' one for coordinates. Here are the fields we used in the Catastici dataset | ||

* function: function of the parcel | * function: function of the parcel | ||

* owner_family_name: owner last name (blank if owner is not an person) | * owner_family_name: owner last name (blank if owner is not an person) | ||

* owner_code: code of owner type | * owner_code: code of owner type | ||

* owner_entity_group: owner entity group | * owner_entity_group: owner entity group standardization (blank if owner is not an entity) | ||

* owner_family_group: owner family group | * owner_family_group: owner family group standardization (blank if owner is not an person) | ||

In order to work on traghetti, we need a way to extract each one from the data set. For this purpose we searched the keywords "traghetto/i" and "gondola/e" in the | In order to work on traghetti, we need a way to extract each one from the data set. For this purpose we searched the keywords "traghetto/i" and "gondola/e" in the ''function'' column of the dataset using regex. Whilst exploring the data during the Entity Analysis, we discovered that the keyword "Libertà" also refers to the traghetti and included it in our regex. This choice will be motivated in the Discussion section. | ||

For Sommarioni dataset, text_data and geojson have different lengths and columns. We prefer geojson file because it has the footprint around the parcel. We will use | For Sommarioni dataset, ''text_data'' and ''geojson'' have different lengths and columns. We prefer the ''geojson'' file because it has the footprint around the parcel. We will use ''parcel_number'' to merge sommarioni into catastici and use ''parcel_type'' field for the type of the parcel, like "building", "courtyard", "sottoportico", "street", "water". | ||

===Entity Analysis=== | ===Entity Analysis=== | ||

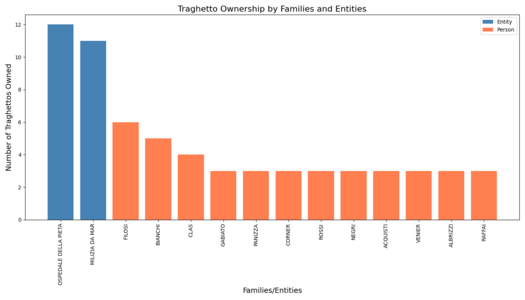

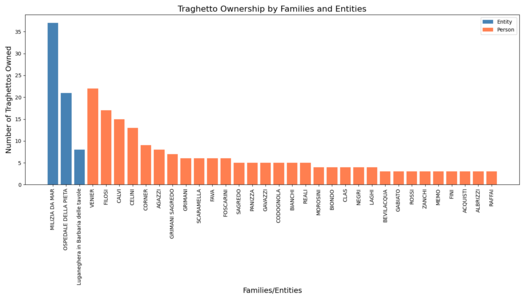

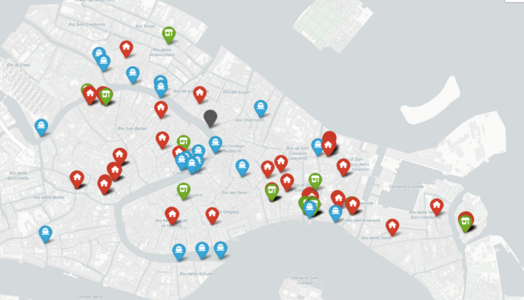

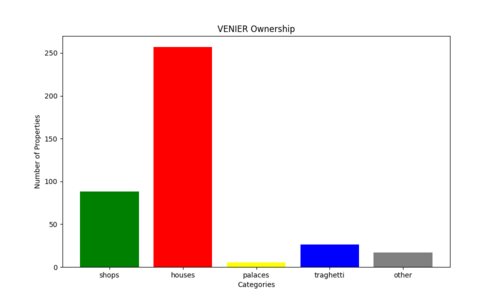

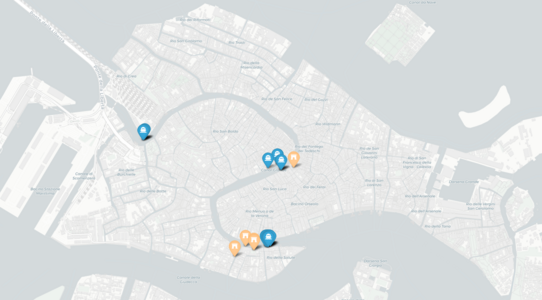

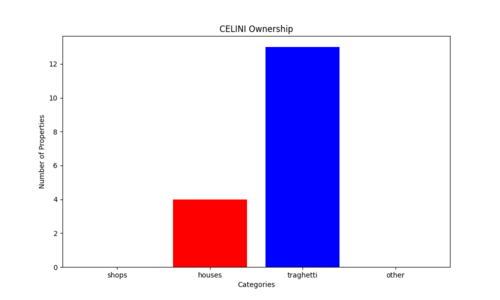

To understand who owns the traghetti, we wanted to delve into several such entities. For this process, we started by extracting all traghetto owners from the data set and made and histogram of traghetto ownership by Entity | To understand who owns the traghetti, we wanted to delve into several such entities. For this process, we started by extracting all traghetto owners from the data set and made and histogram of traghetto ownership by Entity or Family. This gives us an idea of the most important families and entities in the traghetto business. Based on the results, we chose several specific entities that were interesting, for which we did a more in-depth analysis. For these entities, aside from searching them in historical articles, we plotted a histogram of everything that they owned with the following categories: shops, houses, traghetti and other. This already gives us an idea of the kind of entity we are studying, by discussing the number of properties owned, or the percentage of traghetti owned by these entities. We finally plotted these properties in the Venice map, to try and find any patterns for the placement of the traghetti. | ||

===Catastici and Sommarioni merging=== | ===Catastici and Sommarioni merging=== | ||

Here we are going to see what the traghetto in Catastici dataset (1740) change into in Sommarioni dataset (1808). | Here we are going to see what the traghetto in Catastici dataset (1740) change into in Sommarioni dataset (1808). | ||

There are fields indicating the usage of the parcel in both Catastici dataset and Sommarioni dataset, | There are fields indicating the usage of the parcel in both Catastici dataset and Sommarioni dataset, ''function'' and ''parcel_type'', respectively. From the data, we can check how the functions of the parcel change. For example, a traghetti in 1740 in a parcel may still stay as a traghetti, or change into a garden. By merging and aligning the Catastici and Sommarioni dataset, we can see this evolution process. | ||

There are two possible approaches for our dataset merging, id matching and coordinates matching. | There are two possible approaches for our dataset merging, id matching and coordinates matching. | ||

| Line 94: | Line 97: | ||

1. id matching | 1. id matching | ||

We can align the entries in the Catastici dataset with those in the Sommarioni dataset by matching the | We can align the entries in the Catastici dataset with those in the Sommarioni dataset by matching the ''id_napo'' field from the Catastici dataset to the ''parcel_number'' field in the Sommarioni dataset. We were trying to see if we can figure out if the ferries in Catastici dataset became something else in Sommarioni dataset, or which entries in Catastici dataset became ferries in Sommarioni dataset. The id matching could result in exact matching between entries in Catastici dataset and Sommarioni dataset. | ||

2. coordinates matching | 2. coordinates matching | ||

Another way to matching Catastici and Sommarioni dataset, is to match by coordinates. In Catastici dataset, we have the coordinates of the | Another way to matching Catastici and Sommarioni dataset, is to match by coordinates. In Catastici dataset, we have the coordinates of the traghetti, which are individual point coordinates, like Point (12.34334 45.43827). In Sommarioni dataset, we have the footprint around the parcel, demonstrated as a polygon, like POLYGON ((12.3344614 45.4340889, 12.3344839 45.4340411, 12.3344957 45.434044, 12.3344726 45.4340918, 12.3344614 45.4340889)). | ||

From the data, we can check if a traghetti in Castici dataset lies in the footprint of a parcel in Sommarioni dataset, by checking if the point is within the polygon. Thanks to geopandas, it's easy to conduct the check. | From the data, we can check if a traghetti in Castici dataset lies in the footprint of a parcel in Sommarioni dataset, by checking if the point is within the polygon. Thanks to geopandas, it's easy to conduct the check. | ||

| Line 104: | Line 107: | ||

===Origin-Destination Human Mobility Network=== | ===Origin-Destination Human Mobility Network=== | ||

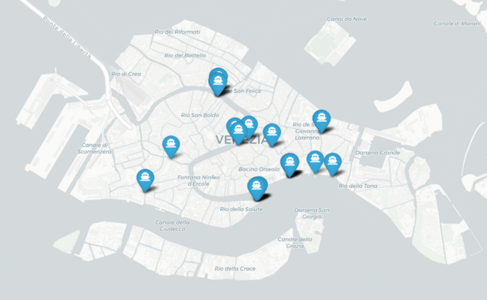

To explore the transport routes and potential usage of ''traghetti'' in Venice during 1740, we | To explore the transport routes and the potential usage of ''traghetti'' in Venice during 1740, we began by analyzing the spatial distribution of land use. The ''catastici 1740'' dataset provides information about property functions, which we classified into meaningful categories to identify residential, commercial, and transport-related areas. | ||

Data Classification | ==== Data Classification ==== | ||

We systematically categorized properties based on keywords extracted from the '''function column'''. This classification forms the foundation for understanding Venice's land use patterns and identifying the locations of homes, workplaces, and ''traghetti'' stations, essential for simulating human mobility. | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align: left; width: 100%;" | {| class="wikitable" style="text-align: left; width: 100%;" | ||

| Line 125: | Line 124: | ||

| Religious/Institutional || chiesa, religious, institution, magazzino, storage || Churches, religious sites, and institutional storage buildings. | | Religious/Institutional || chiesa, religious, institution, magazzino, storage || Churches, religious sites, and institutional storage buildings. | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Traghetto/Squero || | | Traghetto/Squero || traghetto, liberta, squero, gondola || Locations related to ferry crossings (''traghetti'') and boatyards. | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Unknown/Other || - || Entries that do not match any of the defined categories. | | Unknown/Other || - || Entries that do not match any of the defined categories. | ||

|} | |} | ||

The inclusion of the '''Mixed Use''' category reflects the tendency of Venetian residents to combine living and working spaces. Meanwhile, the '''Traghetti/Squero''' category highlights the importance of ferries and boatyards in Venice's unique transport system. | |||

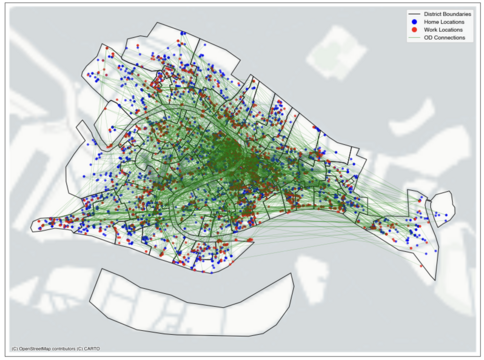

==== Agent Definition ==== | |||

To simulate human mobility, we defined individuals (agents) as those who rented more than one spaces for both '''residential''' and '''commercial purposes'''. Agents were identified through the following steps: | |||

Agent Definition | |||

# Extracted names from both the '''owner''' and '''tenant''' columns in the dataset. | # Extracted names from both the '''owner''' and '''tenant''' columns in the dataset. | ||

# | # Used the '''owner column''' as a fallback when the tenant column was null. | ||

# Defined agents as individuals who rented or owned '''two or more properties'''. | # Defined agents as individuals who rented or owned '''two or more properties'''. | ||

Home-Workplace Extraction | ==== Home-Workplace Extraction ==== | ||

For each identified agent, we extracted one '''home''' and one '''workplace''' | For each identified agent, we extracted one '''home''' and one '''workplace'''. In cases where individuals rented or owned '''multiple properties''', we randomly selected one property with residential class as their home and one property with commercial class as their workplace. | ||

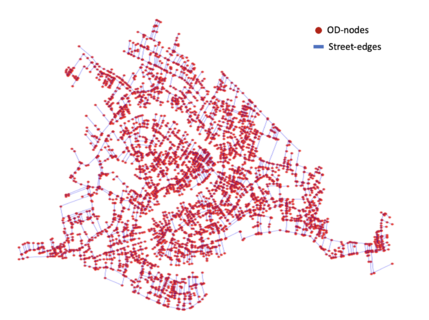

===Network Geometry Engineering=== | ===Network Geometry Engineering=== | ||

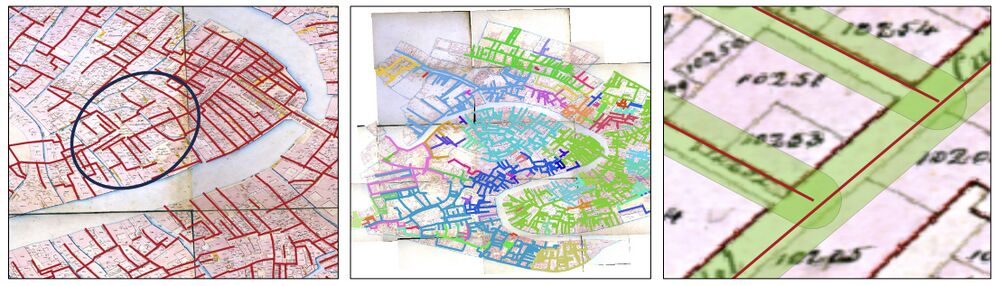

To | To simulate how agents traveled between home and work locations, we utilized the '''Sommarioni 1808 road network''' provided by the Venice Time Machine. Although this dataset does not precisely align with the '''Catastici 1740 dataset''', the absence of road network data from 1740 necessitated its use. A comparison with the [https://cartography.veniceprojectcenter.org/#|'''Lodovico Ughi map (1729)'''] revealed that the road networks were largely consistent, validating its suitability for this analysis. | ||

==== Challenges in Initial Network Data ==== | |||

* | The raw road network data presented significant challenges, including: | ||

* | * Disconnected edges resulting in fragmented paths. | ||

* Multiple unconnected components, preventing comprehensive route analysis. | |||

These issues posed a limitation for network-based simulations, as agents would be unable to traverse between their designated home and work locations effectively. | |||

<gallery widths=1000 heights=290> | <gallery widths=1000 heights=290> | ||

File:Road-cleaning-procedure.jpg|Geometry Engineering Process | File:Road-cleaning-procedure.jpg|'''Geometry Engineering Process''': Unconnected segments (Left); Disconnected components (Center); Buffer tolerance used to auto-link segments (Right). | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

==== Geometry Engineering Techniques ==== | |||

To address these issues and ensure a usable road network, we applied a series of '''geometry engineering techniques''': | |||

# Buffering and Snapping Tools**: We used tools available in the '''QGIS GRASS extension''' to connect nearby, but geometrically disjointed, segments. | |||

# Manual Editing**: Where automated methods failed, we manually edited network geometries to resolve inconsistencies and ensure logical connectivity. | |||

# Validation**: After each step, we validated the network for errors and redundancies, ensuring no excessive or artificial connections were introduced. | |||

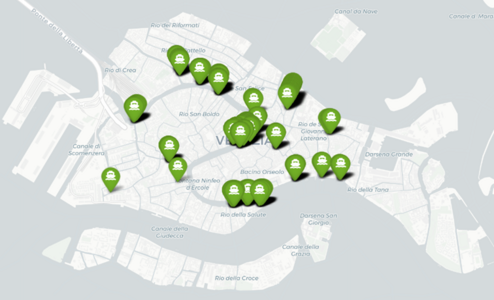

==== Traghetti Routes Integration ==== | |||

For the '''traghetti''' routes, we manually digitized the primary ferry pathways using historical maps as a reference. Recognizing the strategic importance of these routes in Venice's transport system, we assumed that all '''traghetti''' stations were interconnected, enabling seamless movement between any two ferry-serviced locations. | |||

==== Final Output ==== | |||

Through this process, we successfully transformed the road and traghetti networks into a '''fully connected graph'''. This allowed agents to travel between any two points in Venice, whether via roads or ferry routes, enabling robust simulations of human mobility and transportation patterns. | |||

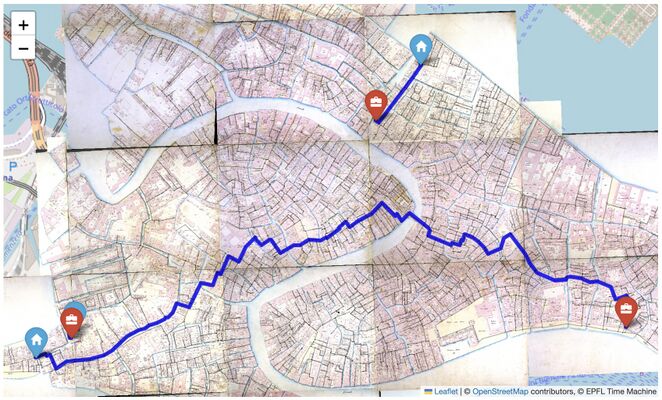

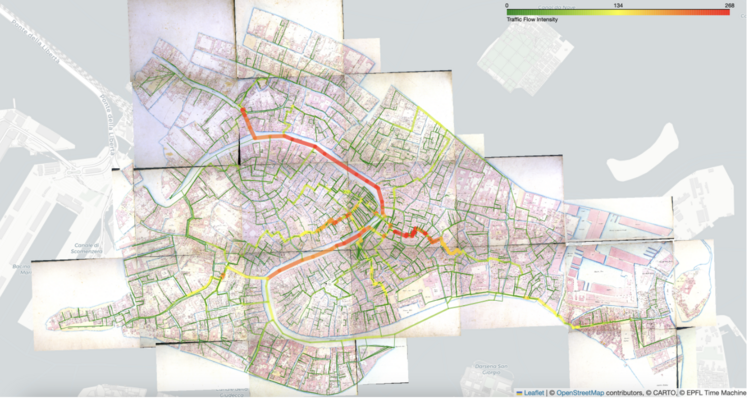

=== Transport Routes Modeling in Venice, 1740 === | === Transport Routes Modeling in Venice, 1740 === | ||

| Line 196: | Line 193: | ||

File:traghetti_ownership_liberta.png|Histogram of ''traghetto'' and ''liberta'' ownership | File:traghetti_ownership_liberta.png|Histogram of ''traghetto'' and ''liberta'' ownership | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

Finally, we found in a Venitian dictionnary written in 1856 that the word ''libertà'' is directly related to the traghetto business and means the “licence” to exploit a Traghetto | Finally, we found in a Venitian dictionnary written in 1856 that the word ''libertà'' is directly related to the traghetto business and means the “licence” to exploit a Traghetto <ref> "Chiamasi tra i nostri Gondolieri il Diritto di tenere una gondola e averne esercizio ad uno de Traghetti della Citta, diritto che si puô esercitare da sè od affittare ad altri o alinerare", DI GIUSEPPE, ''Dizionario del Dialetto Veneziano'', p.369.</ref>. | ||

Thus, based on this evidence, we can affirm that the keyword ''libertà'' is referring to traghetti and we will include them in our analysis. We hypothesize that the difference between ''libertà'' and ''libertà di traghetto'' in our dataset is based on the | Thus, based on this evidence, we can affirm that the keyword ''libertà'' is referring to traghetti and we will include them in our analysis. We hypothesize that the difference between ''libertà'' and ''libertà di traghetto'' in our dataset is based on the fact that it was made by several people, and since all libertà refer to traghetti, some did not write it in full, but only libertà. | ||

===Entity analysis=== | ===Entity analysis=== | ||

| Line 216: | Line 213: | ||

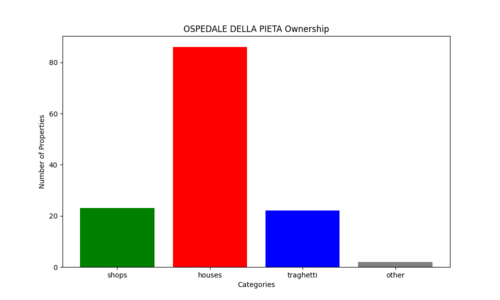

The ''Ospedale della Pietà'' is one of the four ''Ospedali Grandi'', charitable institutions forming the base of the Venitian welfare system. The Ospedale della Pietà was focused on housing abandoned children. These entities were also known throughout Europe as musical institutions, each child they housed receiving basic musical training, and the best performing in the Ospedali's renowned ''cori'' <ref>CURCIO, « Venice's ''Ospedali Grandi'': Music and Cultre in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries », p. 1-2, 8-9.</ref>. It is thus surprising to find this institution this high in the traghetto business, especially when the other ''Ospedali'' do not own any traghetti. | The ''Ospedale della Pietà'' is one of the four ''Ospedali Grandi'', charitable institutions forming the base of the Venitian welfare system. The Ospedale della Pietà was focused on housing abandoned children. These entities were also known throughout Europe as musical institutions, each child they housed receiving basic musical training, and the best performing in the Ospedali's renowned ''cori'' <ref>CURCIO, « Venice's ''Ospedali Grandi'': Music and Cultre in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries », p. 1-2, 8-9.</ref>. It is thus surprising to find this institution this high in the traghetto business, especially when the other ''Ospedali'' do not own any traghetti. | ||

If we look at the Ospedale’s properties, we find that they specialise in housing. Knowing the purpose of the institution this is not surprising, as either to make money to subsidise their charitable work or to pay the famous music teachers, | If we look at the Ospedale’s properties, we find that they specialise in housing. Knowing the purpose of the institution this is not surprising, as either to make money to subsidise their charitable work or to pay the famous music teachers, they would need money, and rent from housing can provide it. What is interesting is that traghetti make up 15% of all properties owned by the institution and almost 50% of non-housing. The traghetti are thus a good portion of the investment from the Ospedale. | ||

<gallery widths=550 heights=300> | <gallery widths=550 heights=300> | ||

File:OSPEDALE DELLA PIETA.png|Types of properties owned by the Ospedale della Pieta | File:OSPEDALE DELLA PIETA.png|Types of properties owned by the Ospedale della Pieta | ||

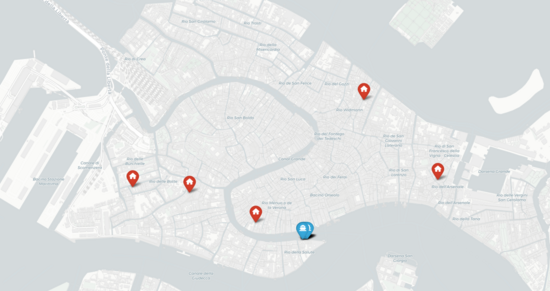

File:Ospedale ownership.png|Map of the properties owned by the Ospedale della Pieta | |||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

Finally, we tried to understand why Ospedale would own traghetti. We made the hypothesis that the placement of the traghetti would be either around their main building, to both give employment to the orphans they would welcome and to allow people to come to their building, or near their shops and houses to facilitate movement between their properties. | Finally, we tried to understand why Ospedale would own traghetti. We made the hypothesis that the placement of the traghetti would be either around their main building, to both give employment to the orphans they would welcome and to allow people to come to their building, or near their shops and houses to facilitate movement between their properties. | ||

Instead, we see the distribution above. We see a high density of ownership around the Ospedale building, while many traghetti and general properties are scattered across the city. Unfortunately, it is hard to provide a satisfactory explanation of this data. Most of the proprieties could come from inheritance, where a childless family would give their properties to a charitable institution, but that does not explain the amount of traghetti owned by the Ospedale. Moreover, no article or book that we have found touches on this specific subject, leaving the only clues to be found probably in the archives of the Ospedale itself. | |||

Instead, we | |||

====Venier==== | ====Venier==== | ||

| Line 232: | Line 227: | ||

<gallery widths=550 heights=300> | <gallery widths=550 heights=300> | ||

File:VENIER.png|Types of properties owned by the Venier family | File:VENIER.png|Types of properties owned by the Venier family | ||

File:Venier palace and traghetto.png|Map of the properties owned by Venier family | |||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

Like the case of the Ospedale, the Venier family owns mostly houses and apartments. Being one of the richest families in Venice this result is not surprising. What is notable is the number of traghetti owned by the family compared to the other noble families, like the Pisani or Grimaldi families (families that had Venitian doges around 1740) <ref>Ibid.</ref>. This discrepancy might be understood by looking at the locations of the Venier’s traghetti. | Like the case of the Ospedale, the Venier family owns mostly houses and apartments. Being one of the richest families in Venice this result is not surprising. What is notable is the number of traghetti owned by the family compared to the other noble families, like the Pisani or Grimaldi families (families that had Venitian doges around 1740) <ref>Ibid.</ref>. This discrepancy might be understood by looking at the locations of the Venier’s traghetti. | ||

This map displays the position of the traghetti and palaces belonging to the Venier family. Unlike the Ospedale map, we can observe that the traghetti are in specific clusters, and mostly near the family’s palaces in the Rialto and in the south of the city. One can then hypothesize that the traghetti owned by the Venier family would serve to connect their palaces in the south to the important centres of the city. | This map displays the position of the traghetti and palaces belonging to the Venier family. Unlike the Ospedale map, we can observe that the traghetti are in specific clusters, and mostly near the family’s palaces in the Rialto and in the south of the city. One can then hypothesize that the traghetti owned by the Venier family would serve to connect their palaces in the south to the important centres of the city. | ||

| Line 245: | Line 238: | ||

<gallery widths=550 heights=300> | <gallery widths=550 heights=300> | ||

File:CELINI.png|Types of properties owned by the Celini family | File:CELINI.png|Types of properties owned by the Celini family | ||

File:Celini traghetto.png|Map of the properties owned by Celini family | |||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

Indeed, the Celini family only owns traghetti and a few houses. It would seem to be a family with a history of working and managing traghetti. | Indeed, the Celini family only owns traghetti and a few houses. It would seem to be a family with a history of working and managing traghetti. | ||

By looking at their ownership | By looking at their ownership map, we can see that all their traghetti are at one end of the grand canal, right in front of the Basilica Santa Maria della Salute. We can then hypothesize that this is a family that has inherited the traghetto business for a long time, and the licence they had was in that specific place, which is an important place to cross the canal. | ||

===Catastici and Sommarioni merging=== | ===Catastici and Sommarioni merging=== | ||

As is shown in Methodology part, we are going to use id matching and coordinates matching to see what the traghetto in Catastici dataset(1740) change into in Sommarioni dataset(1808). | As is shown in Methodology part, we are going to use id matching and coordinates matching to see what the traghetto in Catastici dataset (1740) change into in Sommarioni dataset (1808). | ||

1. id matching | 1. id matching | ||

We conducted id matching first because it's more exact than coordinates matching, However, the entries related to "traghetti" and " | We conducted id matching first because it's more exact than coordinates matching, However, the entries related to "traghetti" and "libertà" in Catastici dataset all have null ''id_napo'' fields. In this way, we cannot match those entries related to "traghetti" and "liberta" in Catastici dataset with the ones in Sommarioni dataset. In other words, id matching is not applicable on the current datasets. | ||

2. coordinates matching | 2. coordinates matching | ||

We found it not feasible to continue the matching with the exact ids, i.e. | We found it not feasible to continue the matching with the exact ids, i.e. ''id_napo'' and ''parcel_number''. Then we turn to check the coordinates of the ferries in the Catastici dataset, and see where these coordinates fall in Sommarioni dataset. We can tell if a coordinates falls into a parcel in Sommarioni dataset by checking if the coordinate falls within the footprint (a polygon) in Sommarioni dataset. | ||

After checking the functions for these matched traghetto, we find 37 traghetto fall into 37 parcels in Sommarioni dataset, respectively. Among these 37 parcels, 30 are courtyards and 7 are buildings. | After checking the functions for these matched traghetto, we find that 37 traghetto fall into 37 parcels in Sommarioni dataset, respectively. Among these 37 parcels, 30 are courtyards and 7 are buildings. | ||

Looking into the owner family names, we find that the VENIER, CODOGNOLA, FOSCARINI, SAGREDO and ROSSI, all [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venetian_nobility noble families in Venice], own 17 out of these 30 traghetto. | Looking into the owner family names, we find that the VENIER, CODOGNOLA, FOSCARINI, SAGREDO and ROSSI, all [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venetian_nobility noble families in Venice], own 17 out of these 30 traghetto. | ||

| Line 318: | Line 309: | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

For those who rent more than 1 properties, the places with class | For those who rent more than 1 properties, the places with class House/Properties were labelled as home locations, while other classes were considered as work locations. | ||

To visualize the spatial distribution of human mobility in 1740 Venice, we constructed the Origin-Destination (OD) network based on agents’ home and workplace locations. The O-D pairs analysis reveals significant spatial patterns in the home-work connections of agents in 1740 Venice. | To visualize the spatial distribution of human mobility in 1740 Venice, we constructed the Origin-Destination (OD) network based on agents’ home and workplace locations. The O-D pairs analysis reveals significant spatial patterns in the home-work connections of agents in 1740 Venice. | ||

| Line 368: | Line 359: | ||

==Conclusion== | ==Conclusion== | ||

This research enabled us to learn more about the relationship between the famous traghetti and the city of Venice during the XVIIIe century. We showed which families were important in the traghetto business. By looking at some of them in more detail, we discovered several patterns for the traghetto ownership, as they can serve to facilitate movement between one’s properties for example, while in some cases no real pattern emerges, and we would need to search the institution’s archives to understand its ownership. We also tried to understand how the traghetto business changed over the decades, by looking at the Sommarioni dataset. Unfortunately, we were no able to find any data, leading us to the hypothesis that, with the change of administration lead by Napoleon’s conquest of the city, the taxation method changed from the rent perceived in 1740 to the clear parcel delimitation provided by the Napoleonic cadastre. | This research enabled us to learn more about the relationship between the famous traghetti and the city of Venice during the XVIIIe century. We showed which families were important in the traghetto business. By looking at some of them in more detail, we discovered several patterns for the traghetto ownership, as they can serve to facilitate movement between one’s properties for example, while in some cases no real pattern emerges, and we would need to search the institution’s archives to understand its ownership. We also tried to understand how the traghetto business changed over the decades, by looking at the Sommarioni dataset. Unfortunately, we were no able to find any data, leading us to the hypothesis that, with the change of administration lead by Napoleon’s conquest of the city, the taxation method changed from the rent perceived in 1740 to the clear parcel delimitation provided by the Napoleonic cadastre. | ||

While our approach was highly data driven, we could also approach this question in a more historical way. Unfortunately, there are not a lot of publicly available sources for this subject, meaning that one should go to the archives of the city and of these different families and institutions to pursue the research. Another way to expand our understanding of traghetti, would be to compare with how they work nowadays. Unfortunately, information about these businesses is not available online, so one would need to go on the terrain to obtain this information. Finally it would also have been interesting to delve more into the tenants (which are the people actually working in the traghetti), though not much can be extracted from our dataset. Indeed, in order to understand their motivations and conditions we would need more historical documents from that era. | |||

However, by combining the street network data and tenant information, we successfully reconstructed agent-based home and work locations, offering a rare glimpse into the mobility patterns of 18th-century Venice. Even today, obtaining such agent-level mobility data is challenging due to strict data privacy regulations. The Catastici 1740 dataset provided a unique opportunity to analyze historical mobility, highlighting the fundamental role of traghetti as critical connectors within the Venetian transport network. | |||

This research not only demonstrates the applicability of modern data-driven methods to historical datasets but also underscores the potential of combining spatial analysis with historical records to answer questions about urban life in the past. | |||

In the future, this approach could be expanded further by integrating additional archival data, familial archives, to refine our understanding of ownership patterns and tenant operations. Moreover, comparing historical findings with the current usage and management of traghetti could provide valuable insights into the continuity and evolution of Venice’s transport system over centuries. | |||

==Appendix== | ==Appendix== | ||

[https://github.com/dhlab-class/fdh-2024-student-projects-ching-chi-andre-renyi Github page] | [https://github.com/dhlab-class/fdh-2024-student-projects-ching-chi-andre-renyi Github page] | ||

[https://trip1ech.github.io/Venice_Mobility_1740/ Interactive WebApp Demo] | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Latest revision as of 22:56, 18 December 2024

Introduction and Motivation

The city of Venice is widely known for its network of canals and its iconic ferries, know as traghetti. While nowadays they mainly serve as a tourist attraction, the traghetti have played a vital role in the daily life of Venetians since the early days of the city, by enabling the movement of both goods and people [1]. By looking at ownership data from a Venetian census of 1740, this study will seek to explore who owned and how the Venetian traghetti were operated during this period.

This research will focus on three main aspects. First, we will investigate the ownership of the traghetti and try to identify the prominent entities that controlled them. We will then try to understand the motivations behind this ownership, by looking at other business ventures of the entity, its layout in the city or other historical motives not necessarily found in the data.

Secondly, we will conduct a spatial analysis in order to explore the distribution of traghetti across Venice. Using the geographical data, we will try to understand the placement of the ferries throughout the city and what kind economic or societal factors determined their position. Finally, by using another historical record (the Venetian cadastre of 1808), we will try to analyse how the ownership and placement of the traghetti evolved trough the 68 years separating the two datasets.

Deliverables

- Python scripts production plots and maps for the entity analysis (entity_analysis folder)

- Jupyter Notebooks for matching Catastici and Sommarioni dataset and the results (catastici-to-sommarioni folder)

- Jupyter Notebooks for mobility analysis(mobility-analysis folder)

Project Timeline & Milestones

| Week | Task | Status |

|---|---|---|

| 14.10 - 20.10 | - Define research question | ✓ |

| Autumn Vacation | -------------------------- | ✓ |

| 28.10 - 03.11 | - Find and read litterature | ✓ |

| 04.11 - 10.11 | - Read litterature

- Extract owner data and provide early visualisations |

✓ |

| 11.11 - 17.11 | - Midterm presentations

- Visualisation tool for historical maps |

✓ |

| 18.11 - 24.11 | - Catastici and Sommarioni alignment

- Entity owned distribution - Traghetti Rental Prices Analysis |

✓ |

| 25.11 - 01.12 | - Catastici and Sommarioni analysis (ownership change, ...)

- Adapt previous analysis to new 'libertà' keyword - Spatial analysis of traghetti - Start writing the wiki |

✓ |

| 02.12 - 08.12 |

- Analyse tenents - Specific families/entities analysis - Compare results to present day data (if available) - Continue writing wiki |

✓ |

| 09.12 - 15.12 | - Finish writing the wiki | ✓ |

| 16.12 - 22.12 | - Spare week | ✓ |

Milestones

Milestone 1 (17.11): Understand what traghetti are and have an idea of what their role is in the city. Provide early visualizations tools for further analysis. Define our research question.

Milestone 2 (01.12): Properly establish the methodology and the tools for the analysis. Finish extracting data and align the datasets.

Milestone 3 (18.12): Finish analysis of the project and write the wiki. The code is clean, annotated and ready to be shared.

Methodology

Data Extraction

For Catastici dataset, text_data and geojson are exactly the same, except for the geometry column. The difference in geometry column is likely that they adopted difference coordinate systems, and we prefer to use the geojson one for coordinates. Here are the fields we used in the Catastici dataset

- function: function of the parcel

- owner_family_name: owner last name (blank if owner is not an person)

- owner_code: code of owner type

- owner_entity_group: owner entity group standardization (blank if owner is not an entity)

- owner_family_group: owner family group standardization (blank if owner is not an person)

In order to work on traghetti, we need a way to extract each one from the data set. For this purpose we searched the keywords "traghetto/i" and "gondola/e" in the function column of the dataset using regex. Whilst exploring the data during the Entity Analysis, we discovered that the keyword "Libertà" also refers to the traghetti and included it in our regex. This choice will be motivated in the Discussion section.

For Sommarioni dataset, text_data and geojson have different lengths and columns. We prefer the geojson file because it has the footprint around the parcel. We will use parcel_number to merge sommarioni into catastici and use parcel_type field for the type of the parcel, like "building", "courtyard", "sottoportico", "street", "water".

Entity Analysis

To understand who owns the traghetti, we wanted to delve into several such entities. For this process, we started by extracting all traghetto owners from the data set and made and histogram of traghetto ownership by Entity or Family. This gives us an idea of the most important families and entities in the traghetto business. Based on the results, we chose several specific entities that were interesting, for which we did a more in-depth analysis. For these entities, aside from searching them in historical articles, we plotted a histogram of everything that they owned with the following categories: shops, houses, traghetti and other. This already gives us an idea of the kind of entity we are studying, by discussing the number of properties owned, or the percentage of traghetti owned by these entities. We finally plotted these properties in the Venice map, to try and find any patterns for the placement of the traghetti.

Catastici and Sommarioni merging

Here we are going to see what the traghetto in Catastici dataset (1740) change into in Sommarioni dataset (1808). There are fields indicating the usage of the parcel in both Catastici dataset and Sommarioni dataset, function and parcel_type, respectively. From the data, we can check how the functions of the parcel change. For example, a traghetti in 1740 in a parcel may still stay as a traghetti, or change into a garden. By merging and aligning the Catastici and Sommarioni dataset, we can see this evolution process.

There are two possible approaches for our dataset merging, id matching and coordinates matching.

1. id matching

We can align the entries in the Catastici dataset with those in the Sommarioni dataset by matching the id_napo field from the Catastici dataset to the parcel_number field in the Sommarioni dataset. We were trying to see if we can figure out if the ferries in Catastici dataset became something else in Sommarioni dataset, or which entries in Catastici dataset became ferries in Sommarioni dataset. The id matching could result in exact matching between entries in Catastici dataset and Sommarioni dataset.

2. coordinates matching

Another way to matching Catastici and Sommarioni dataset, is to match by coordinates. In Catastici dataset, we have the coordinates of the traghetti, which are individual point coordinates, like Point (12.34334 45.43827). In Sommarioni dataset, we have the footprint around the parcel, demonstrated as a polygon, like POLYGON ((12.3344614 45.4340889, 12.3344839 45.4340411, 12.3344957 45.434044, 12.3344726 45.4340918, 12.3344614 45.4340889)).

From the data, we can check if a traghetti in Castici dataset lies in the footprint of a parcel in Sommarioni dataset, by checking if the point is within the polygon. Thanks to geopandas, it's easy to conduct the check.

Origin-Destination Human Mobility Network

To explore the transport routes and the potential usage of traghetti in Venice during 1740, we began by analyzing the spatial distribution of land use. The catastici 1740 dataset provides information about property functions, which we classified into meaningful categories to identify residential, commercial, and transport-related areas.

Data Classification

We systematically categorized properties based on keywords extracted from the function column. This classification forms the foundation for understanding Venice's land use patterns and identifying the locations of homes, workplaces, and traghetti stations, essential for simulating human mobility.

| **Category** | **Keywords** | **Description** |

|---|---|---|

| Residential | casa, appartamento, casetta | Properties serving as houses, apartments, or residences. |

| Commercial/Retail | bottega, magazen | Shops, warehouses, and commercial buildings. |

| Mixed Use (Residential + Commerce) | casa e bottega | Properties used for both residential and commercial purposes. |

| Religious/Institutional | chiesa, religious, institution, magazzino, storage | Churches, religious sites, and institutional storage buildings. |

| Traghetto/Squero | traghetto, liberta, squero, gondola | Locations related to ferry crossings (traghetti) and boatyards. |

| Unknown/Other | - | Entries that do not match any of the defined categories. |

The inclusion of the Mixed Use category reflects the tendency of Venetian residents to combine living and working spaces. Meanwhile, the Traghetti/Squero category highlights the importance of ferries and boatyards in Venice's unique transport system.

Agent Definition

To simulate human mobility, we defined individuals (agents) as those who rented more than one spaces for both residential and commercial purposes. Agents were identified through the following steps:

- Extracted names from both the owner and tenant columns in the dataset.

- Used the owner column as a fallback when the tenant column was null.

- Defined agents as individuals who rented or owned two or more properties.

Home-Workplace Extraction

For each identified agent, we extracted one home and one workplace. In cases where individuals rented or owned multiple properties, we randomly selected one property with residential class as their home and one property with commercial class as their workplace.

Network Geometry Engineering

To simulate how agents traveled between home and work locations, we utilized the Sommarioni 1808 road network provided by the Venice Time Machine. Although this dataset does not precisely align with the Catastici 1740 dataset, the absence of road network data from 1740 necessitated its use. A comparison with the Lodovico Ughi map (1729) revealed that the road networks were largely consistent, validating its suitability for this analysis.

Challenges in Initial Network Data

The raw road network data presented significant challenges, including:

- Disconnected edges resulting in fragmented paths.

- Multiple unconnected components, preventing comprehensive route analysis.

These issues posed a limitation for network-based simulations, as agents would be unable to traverse between their designated home and work locations effectively.

Geometry Engineering Techniques

To address these issues and ensure a usable road network, we applied a series of geometry engineering techniques:

- Buffering and Snapping Tools**: We used tools available in the QGIS GRASS extension to connect nearby, but geometrically disjointed, segments.

- Manual Editing**: Where automated methods failed, we manually edited network geometries to resolve inconsistencies and ensure logical connectivity.

- Validation**: After each step, we validated the network for errors and redundancies, ensuring no excessive or artificial connections were introduced.

Traghetti Routes Integration

For the traghetti routes, we manually digitized the primary ferry pathways using historical maps as a reference. Recognizing the strategic importance of these routes in Venice's transport system, we assumed that all traghetti stations were interconnected, enabling seamless movement between any two ferry-serviced locations.

Final Output

Through this process, we successfully transformed the road and traghetti networks into a fully connected graph. This allowed agents to travel between any two points in Venice, whether via roads or ferry routes, enabling robust simulations of human mobility and transportation patterns.

Transport Routes Modeling in Venice, 1740

After preparing the data, we simulated agents' movements between home and work locations using a shortest path algorithm to determine their daily commute routes. The calculated routes were then aggregated to analyze traffic flow within the road network.

We assess the functional role of the traghetti, by comparing traffic flow under two scenarios:

- Using the road network only.

- Allowing agents to travel via both the road network and the traghetti network.

By analyzing the flow differences between these two scenarios, we were able to better understand the impact and importance of the traghetti in Venice's transportation system during the 18th century.

Discussion

Data Extraction

While at first we did not think to include the key word libertà in our traghetto research, we found that they also refers to traghetti. Firstly, all traghetto entries in our dataset are in the form of libertà di traghetto, while all libertà entries appear jointly with traghetto or alone. Moreover, when we plot libertà entries on the map, their location appear in the same places, or as we would expect traghettos to appear.

In addition, we found that ownership stayed relatively similar with or without the addition of the libertà keyword. We still find Filosi or Corner at the top of the families list and Milizia da Mar or Ospedale della Pietà at the top of the entities list.

Finally, we found in a Venitian dictionnary written in 1856 that the word libertà is directly related to the traghetto business and means the “licence” to exploit a Traghetto [2]. Thus, based on this evidence, we can affirm that the keyword libertà is referring to traghetti and we will include them in our analysis. We hypothesize that the difference between libertà and libertà di traghetto in our dataset is based on the fact that it was made by several people, and since all libertà refer to traghetti, some did not write it in full, but only libertà.

Entity analysis

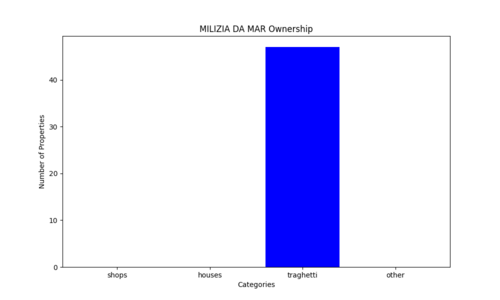

As discussed in the Methodology section, we started by plotting the traghetto ownership (for visibility, we excluded any entity or family that owns two or less traghetti):

In the entity column, two stand out: Milizia da Mar and Ospedale della Pietà. We will choose to focus on these two. Concerning the families, several stand out, but we will choose to focus on the families Venier and Celini.

Milizia da Mar

The Milizia da Mar is the name of the navy of Venice. Knowing this fact, and the importance of traghetti in the mobility of the city, it is natural that this organ would own this crucial utility. This is shown in the following histogram:

Ospedale della Pietà

The Ospedale della Pietà is one of the four Ospedali Grandi, charitable institutions forming the base of the Venitian welfare system. The Ospedale della Pietà was focused on housing abandoned children. These entities were also known throughout Europe as musical institutions, each child they housed receiving basic musical training, and the best performing in the Ospedali's renowned cori [3]. It is thus surprising to find this institution this high in the traghetto business, especially when the other Ospedali do not own any traghetti.

If we look at the Ospedale’s properties, we find that they specialise in housing. Knowing the purpose of the institution this is not surprising, as either to make money to subsidise their charitable work or to pay the famous music teachers, they would need money, and rent from housing can provide it. What is interesting is that traghetti make up 15% of all properties owned by the institution and almost 50% of non-housing. The traghetti are thus a good portion of the investment from the Ospedale.

Finally, we tried to understand why Ospedale would own traghetti. We made the hypothesis that the placement of the traghetti would be either around their main building, to both give employment to the orphans they would welcome and to allow people to come to their building, or near their shops and houses to facilitate movement between their properties.

Instead, we see the distribution above. We see a high density of ownership around the Ospedale building, while many traghetti and general properties are scattered across the city. Unfortunately, it is hard to provide a satisfactory explanation of this data. Most of the proprieties could come from inheritance, where a childless family would give their properties to a charitable institution, but that does not explain the amount of traghetti owned by the Ospedale. Moreover, no article or book that we have found touches on this specific subject, leaving the only clues to be found probably in the archives of the Ospedale itself.

Venier

The Venier noble family is one of the most important families in Venice, notably having several Doges throughout Venice's existence [4]. As such, seeing that they are the family owning the most traghettos, it would be interesting to analyse them further. Like the previous instances, we started by looking at the family’s ownership situation. In this case, we included palaces as a separate category to show the social status of the Veniers.

Like the case of the Ospedale, the Venier family owns mostly houses and apartments. Being one of the richest families in Venice this result is not surprising. What is notable is the number of traghetti owned by the family compared to the other noble families, like the Pisani or Grimaldi families (families that had Venitian doges around 1740) [5]. This discrepancy might be understood by looking at the locations of the Venier’s traghetti.

This map displays the position of the traghetti and palaces belonging to the Venier family. Unlike the Ospedale map, we can observe that the traghetti are in specific clusters, and mostly near the family’s palaces in the Rialto and in the south of the city. One can then hypothesize that the traghetti owned by the Venier family would serve to connect their palaces in the south to the important centres of the city.

Celini

Unlike the Veniers, the Celini family is not a noble family and not much is known about them. Thus, their position as the fourth family owning the most traghetti is remarkable. We can look at their ownership status to try and learn more about the family.

Indeed, the Celini family only owns traghetti and a few houses. It would seem to be a family with a history of working and managing traghetti.

By looking at their ownership map, we can see that all their traghetti are at one end of the grand canal, right in front of the Basilica Santa Maria della Salute. We can then hypothesize that this is a family that has inherited the traghetto business for a long time, and the licence they had was in that specific place, which is an important place to cross the canal.

Catastici and Sommarioni merging

As is shown in Methodology part, we are going to use id matching and coordinates matching to see what the traghetto in Catastici dataset (1740) change into in Sommarioni dataset (1808).

1. id matching

We conducted id matching first because it's more exact than coordinates matching, However, the entries related to "traghetti" and "libertà" in Catastici dataset all have null id_napo fields. In this way, we cannot match those entries related to "traghetti" and "liberta" in Catastici dataset with the ones in Sommarioni dataset. In other words, id matching is not applicable on the current datasets.

2. coordinates matching

We found it not feasible to continue the matching with the exact ids, i.e. id_napo and parcel_number. Then we turn to check the coordinates of the ferries in the Catastici dataset, and see where these coordinates fall in Sommarioni dataset. We can tell if a coordinates falls into a parcel in Sommarioni dataset by checking if the coordinate falls within the footprint (a polygon) in Sommarioni dataset.

After checking the functions for these matched traghetto, we find that 37 traghetto fall into 37 parcels in Sommarioni dataset, respectively. Among these 37 parcels, 30 are courtyards and 7 are buildings.

Looking into the owner family names, we find that the VENIER, CODOGNOLA, FOSCARINI, SAGREDO and ROSSI, all noble families in Venice, own 17 out of these 30 traghetto.

| Name | Count |

|---|---|

| VENIER | 5 |

| CODOGNOLA | 5 |

| (missing value) | 4 |

| GRIMANI SAGREDO | 3 |

| FOSCARINI | 3 |

| PANIZZA | 3 |

| SAGREDO | 2 |

| FILOSI | 2 |

| ROSSI | 2 |

| ALBRICI | 2 |

| RAFFAI | 2 |

| FAVA | 1 |

| CORNER | 1 |

| BERNARDI | 1 |

| TESSER | 1 |

Unfortunately, in the Sommarioni geojson dataset, there are no fields indicating the name of the owner, so we cannot compare the ownership here with the Catastici dataset.

To sum up, for the matching of Catastici and Sommarioni dataset, we find that the id matching doesn't work in our situation, and in coordinates matching, we didn't find any matched parcel in Sommarioni that is a traghetti. One possible reason could be Sommarioni is a cadastre (land registration) it would not show boats in the river but only parcels of land, showing that the way taxation worked changed during the 68 years separating the datasets.

Origin-Destination Human Mobility Network

The classification result highlights the dense residential areas in the northern and southern regions, with commercial hubs concentrated in the central areas. The traghetti locations emphasize the city’s reliance on waterborne transportation, complementing the street networks to facilitate movement and trade.

For those who rent more than 1 properties, the places with class House/Properties were labelled as home locations, while other classes were considered as work locations.

To visualize the spatial distribution of human mobility in 1740 Venice, we constructed the Origin-Destination (OD) network based on agents’ home and workplace locations. The O-D pairs analysis reveals significant spatial patterns in the home-work connections of agents in 1740 Venice.

By the links between agents’ homes and workplaces, we can observe that the central districts emerged as key hubs of activity, exhibiting a high density of destination points. This reflects the concentration commercial properties within the core areas, aligning with the urban fabric of Venice at the time.

Furthermore, in the Ghetto area, we observe a significant number of intra-regional OD pairs, indicating localized movement within this district. This aligns with the historical context, as the Jewish population was confined to the Ghetto during specific hours of the day.

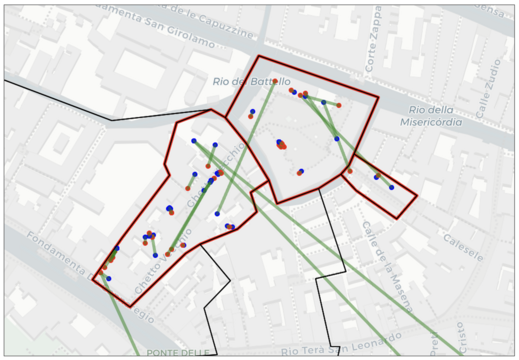

Network Geometry Engineering

After completing a series of geometry engineering procedures using GIS software, we obtained a fully connected street network of Venice. This process ensured that all segments are topologically correct and fully integrated, enabling seamless movement across the network.

The Origin-Destination (OD) points were then projected onto the refined street network, making them ready for subsequent analysis of human mobility patterns.

The traghetti routes—the key gondola crossings in Venice—were incorporated into the network. Notably, access to these traghetti routes is only allowed at designated traghetto locations identified in the catastici of 1740. The completion of both road and canal network data provides a foundation for modeling mobility and transportation patterns in historical Venice.

Transport Routes Modeling in Venice

1. Using the street network only

Streets with a high concentration of shops and commercial properties, such as Ruga Vecchia San Giovanni (known for its activity even today), tend to experience significant traffic and become bustling centers of activity.

When agents are restricted to using only the street network, the connectivity of bridges plays a crucial role. A substantial amount of traffic is observed in areas near bridges, as these crossings provide the only way for individuals to traverse canals. In particular, the Ponte di Rialto, one of the most prominent bridges in Venice, becomes an exceptionally busy hub of movement.

2. Allowing agents to travel via both the road network and the traghetti network.

However, when traghetti are available as a transportation option, the travel patterns in Venice change significantly. A high concentration of traffic flow can be observed along the Grand Canal, reflecting its central role in facilitating movement.

In particular, residents from the northern districts—primarily residential areas—can efficiently travel across the canals via traghetti to access the commercial center for business activities. This highlights the importance of traghetti in reducing travel constraints and enhancing mobility across Venice’s unique urban system in 18th century.

Conclusion

This research enabled us to learn more about the relationship between the famous traghetti and the city of Venice during the XVIIIe century. We showed which families were important in the traghetto business. By looking at some of them in more detail, we discovered several patterns for the traghetto ownership, as they can serve to facilitate movement between one’s properties for example, while in some cases no real pattern emerges, and we would need to search the institution’s archives to understand its ownership. We also tried to understand how the traghetto business changed over the decades, by looking at the Sommarioni dataset. Unfortunately, we were no able to find any data, leading us to the hypothesis that, with the change of administration lead by Napoleon’s conquest of the city, the taxation method changed from the rent perceived in 1740 to the clear parcel delimitation provided by the Napoleonic cadastre.

While our approach was highly data driven, we could also approach this question in a more historical way. Unfortunately, there are not a lot of publicly available sources for this subject, meaning that one should go to the archives of the city and of these different families and institutions to pursue the research. Another way to expand our understanding of traghetti, would be to compare with how they work nowadays. Unfortunately, information about these businesses is not available online, so one would need to go on the terrain to obtain this information. Finally it would also have been interesting to delve more into the tenants (which are the people actually working in the traghetti), though not much can be extracted from our dataset. Indeed, in order to understand their motivations and conditions we would need more historical documents from that era.

However, by combining the street network data and tenant information, we successfully reconstructed agent-based home and work locations, offering a rare glimpse into the mobility patterns of 18th-century Venice. Even today, obtaining such agent-level mobility data is challenging due to strict data privacy regulations. The Catastici 1740 dataset provided a unique opportunity to analyze historical mobility, highlighting the fundamental role of traghetti as critical connectors within the Venetian transport network.

This research not only demonstrates the applicability of modern data-driven methods to historical datasets but also underscores the potential of combining spatial analysis with historical records to answer questions about urban life in the past.

In the future, this approach could be expanded further by integrating additional archival data, familial archives, to refine our understanding of ownership patterns and tenant operations. Moreover, comparing historical findings with the current usage and management of traghetti could provide valuable insights into the continuity and evolution of Venice’s transport system over centuries.

Appendix

References

BOERIO, Giuseppe, Dizionario del dialetto veneziano, Venice: Tipografia di Giovanni Cecchini, 1856, 976 p., URL:https://www.google.ch/books/edition/Dizionario_del_dialetto_veneziano/OGwoAAAAYAAJ?hl=it&gbpv=0#pli=1

CURCIO, Alison, « Venice's Ospedali Grandi: Music and Culture in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries », Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology, Vol 3, n°1, 2010, 14 p.

HUFFMAN, Kristin Love, A View of Venice: Portrait of a Renaissance City, Durham: Duke University Press, 2024, 414 p.

QUILLIEN, Robin, « Apprentissages et voies d’accès au métier de barcarolo à Venise à l’époque moderne (XVIe-XVIIIe siècle) », Mélanges de l’École française de Rome - Italie et Méditerranée modernes et contemporaines, n°131-2, 2019, p. 273-283, DOI:https://doi.org/10.4000/mefrim.6651

ZANELLI, Guglielmo, « Gondole e traghetti », Matematica e cultura, n°1, 2011, p. 59-66, DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-88-470-1854-9_5

- ↑ ZANELLI, « Gondole et traghetti », p. 60-61.

- ↑ "Chiamasi tra i nostri Gondolieri il Diritto di tenere una gondola e averne esercizio ad uno de Traghetti della Citta, diritto che si puô esercitare da sè od affittare ad altri o alinerare", DI GIUSEPPE, Dizionario del Dialetto Veneziano, p.369.

- ↑ CURCIO, « Venice's Ospedali Grandi: Music and Cultre in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries », p. 1-2, 8-9.

- ↑ DURSTELLER, A Companion to Venetian History, 1400-1797, p. 959.

- ↑ Ibid.