Acoustic Features and Musical Identity: Exploring Genres and Artists’ Social Gender

Introduction

This project explores whether large-scale musical data reveal systematic acoustic differences related to artists’ declared gender. While gender inequalities in the music industry are well documented in terms of representation, professional roles, and career trajectories, it remains unclear whether these structural disparities leave detectable traces in the music itself. By combining audio feature analysis, enriched metadata, and statistical modeling, this study provides a descriptive look at possible acoustic patterns across different artist characteristics.

Motivation

Gender inequalities in the music industry

Gender disparities in the music industry are widely documented. According to the USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative, women accounted for only 30% of artists appearing in the 2022 Billboard Hot 100 Year-End Chart, while in 2021, 76.7% of credited artists were men.[1] Imbalance is even more pronounced in technical and creative roles: between 2012 and 2017, women represented only 12.3% of songwriters and 2.1% of producers credited on the 600 most popular Billboard songs.[2]

Large-scale metadata studies based on repositories (such as MusicBrainz) confirm that women constitute a minority of identified artists and that gendered patterns are observable across collaboration networks, career trajectories, and musical outputs.[3] These patterns have been linked to structural factors including unequal access to production technologies, professional network segregation, and biased evaluation mechanisms. [4]

However, these inequalities have primarily been studied through sociological and metadata-based approaches focusing on representation and visibility. Whether and how such structural disparities manifest in the acoustic properties of music, remains relatively unexplored. This is an important gap: if differences in access to resources, production environments, and industry networks affect how music is made, we might expect to see systematic differences in the music itself.

Acoustic features reflect the material outcome of musical production. Measures like timbre, pitch distribution, tempo, and loudness capture aspects of musical expression shaped by compositional choices, production practices, available technology, and stylistic conventions. All of these factors can be influenced by the social and professional conditions under which artists work. Importantly, any acoustic differences found in this study are understood as the result of social, stylistic, technical, and professional processes, not as biological or essential distinctions. In this sense, acoustic analysis is a way of studying cultural artifacts shaped by gendered structures in the music industry.

Research questions

This study has three main goals. First, it establishes empirical baselines for a dimension of musical diversity that has received little attention in computational music analysis. Second, by documenting acoustic variation across artist demographics, it contributes to broader discussions of representation in cultural production. Third, understanding these patterns lays the groundwork for considering how music information systems might interact with or amplify existing disparities.

Modern music recommendation systems rely on collaborative filtering and content-based models that measure similarity using acoustic features. [5] [6] .Research has shown that these systems often reproduce existing inequalities, mainly through popularity bias and feedback loops.[7] If systematic acoustic differences exist across artist characteristics, this raises questions about how content-based representations might interact with recommendation biases.

It is important to note that this project does not evaluate recommendation algorithms or make causal claims. Instead, it offers a descriptive look at acoustic features in a subset of the Million Song Dataset, examining whether meaningful patterns appear when artists are grouped by declared gender. The analysis is exploratory, aiming to document the presence, direction, and magnitude of potential associations.

This analysis is guided by three research questions:

RQ1: Do systematic acoustic differences exist between works associated with male and female artists?

RQ2: Which acoustic dimensions contribute most strongly to any observed differences?

RQ3: Do acoustic patterns vary across musical genres, suggesting genre-specific dynamics?

By focusing on measurable patterns, this study provides a data-driven perspective on gender representation in music while acknowledging the limitations and complexities of both the data and the analytical approach.

Deliverables and methods

Deliverable

Datasets

The analyses presented in this project rely on a curated subset extracted from the Million Song Dataset (MSD). Although the MSD was originally released as a million song collection, the full dataset is no longer easily accessible in its original form due to its size and age. This study therefore uses a publicly available 10 000 songs subset derived from the original release.[8]

All files in the MSD subset were processed through recursive directory traversal. Each HDF5 file was opened using the h5py library, and metadata from three internal groups (/metadata/songs, /analysis/songs, and /musicbrainz/songs) were extracted using a routine designed to handle missing or heterogeneous fields. In total, 54 attributes were collected per track, including artist identifiers, song-level metadata, and acoustic descriptors such as tempo and loudness. All extracted metadata were compiled into a consolidated tabular dataset.

Additional information, including declared artist gender and genre labels, was obtained from the MusicBrainz API. Artist identifiers (artist_mbid) from the Million Song Dataset were used to query the API, following usage rules such as rate limits and user-agent requirements. The field genre_principal was derived from artist tags retrieved via the API. Tags were matched against a predefined mapping that associates common tag keywords with a controlled set of main genres. For each artist, the principal genre was defined as the genre with the highest number of matching tags. Artists for whom no tags matched the mapping were assigned no principal genre.

Segment-level acoustic features were extracted for each track to create compact representations of the music. For every song, the twelve-dimensional arrays segments_pitches and segments_timbre were loaded. To ensure statistical independence, all analyses were done at the artist level. For each artist, segment-level features were averaged across all their tracks for the twelve timbre coefficients and twelve pitch-class profile coefficients. Two global descriptors, loudness and tempo, were also included.

The final dataset included detailed track and artist-level information. It contained basic identifiers (artist_name, artist_mbid, song_id, track_id), track metadata (title, release, year, duration, key, mode, tempo, time_signature, loudness, energy, danceability), and artist-related metadata (gender, country, continent, tags, genre_principal, begin_date, end_date). Acoustic features were represented by 26 variables, including twelve pitch-class profile means (pitch_0_mean to pitch_11_mean), twelve timbre coefficients (timbre_0_mean to timbre_11_mean), and global descriptors (loudness and tempo). Additional derived features included principal components of timbre (timbre_pc1 to timbre_pc3) and z-scored versions of timbre PCs, loudness, tempo, and duration. It contained 4681 songs (including 748 artists).

Acoustic variables

Statistical results

The core output of this project is a comprehensive set of statistical analyses, including:

- Univariate tests of gender differences (RQ1), with effect sizes and FDR-adjusted p-values

- Feature importance analysis from Random Forest classification (RQ2)

- Two-way ANOVAs examining genre moderation of gender effects (RQ3)

- Robustness analyses, including resampling, outlier checks, and PCA

Methods

The analytical pipeline followed a three-stage approach: exploratory visual analysis, formal statistical modeling to address the research questions, and robustness analyses to assess the stability of the findings.

Part 1: Exploratory visual analysis

Exploratory analyses were conducted to examine the structure of the acoustic feature space, identify potential outliers, and inspect the distribution of metadata variables such as gender and genre. Acoustic features were standardized to zero mean and unit variance.

Dimensionality reduction was performed using t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) with three components, perplexity 30, and PCA initialization to preserve local acoustic similarity patterns. A web-based interface built with the Dash framework enabled interactive exploration of the acoustic space. Users can filter tracks by artist gender, genre, geography, and release year, view metadata for each track, and identify its five nearest neighbors in the embedded space.

This exploratory component served primarily as a diagnostic and interpretative tool rather than a basis for formal inference. Observations confirmed that genre showed partial clustering, while gender did not form visible clusters, highlighting the need for formal statistical testing.

Part 2: Statistical modeling

Formal analyses were conducted at the artist level to address the three research questions:

RQ1: Welch’s independent-samples t-tests compared artist-level mean acoustic profiles across gender groups for all 26 acoustic variables. P-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) procedure, and effect sizes were quantified using Cohen’s d.

RQ2: A Random Forest classifier was trained to predict artist gender from the full acoustic feature set. The model pipeline included z-score standardization and balanced class weights. Performance was evaluated with 5-fold stratified cross-validation using balanced accuracy, ROC–AUC, and F1-score. Feature importance was assessed using permutation importance on the fitted model.

RQ3: Two-way ANOVAs were conducted for the five most significant variables from RQ1, with fixed effects for artist gender, principal genre, and their interaction (Gender × Genre). Analyses were limited to genres with sufficient representation (≥15 male and ≥5 female artists). Acoustic variables were standardized prior to modeling.

Supplementary Analyses: Robustness checks focused on the most significant variable (timbre_3_mean), including balanced resampling and exclusion of extreme outliers (>3 standard deviations). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied to the standardized acoustic feature set using a balanced artist sample.

Part 3: Dataset representativity assessment

The representativity of the 10,000-track subset was evaluated by comparing summary statistics for key acoustic variables with those reported in the original Million Song Dataset documentation.

All analyses were implemented in a fully documented and reproducible codebase: https://github.com/camilledupr/FDH-project

Project timeline

| Week | Task |

|---|---|

| 01.10 - 02.10 | Project presentation and topic selection |

| 08.10 - 09.10 | Selection of Million Song Dataset subset |

| 15.10 - 16.10 | HDF5 file extraction, MusicBrainz API integration |

| 22.10 - 23.11 | Week Off |

| 29.10 - 30.10 | Metadata enrichment and genre classification |

| 05.11 - 06.11 | MVP definition: t-SNE visualization and statistical pipeline |

| 12.11 - 13.11 | Midterm presentations |

| 19.11 - 20.11 | Development of Dash interactive interface |

| 26.11 - 27.11 | RQ1 and RQ2 statistical analyses |

| 03.12 - 04.12 | RQ3 ANOVA analyses, sensitivity analyses, representativity assessment |

| 10.12 - 11.12 | Results interpretation, Wiki and GitHub documentation |

| 17.12 - 18.12 | Final deliverables and presentation |

Results

RQ1: Acoustic differences and artist gender

The artist-level univariate analysis, based on Welch's t-tests with False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction, shows clear acoustic differences between male and female artists. Among the 26 acoustic variables kept after preprocessing, eleven show statistically significant differences (PFDR < 0.05).

Table 1: Acoustic Variables with Significant Gender Differences (Welch's t-test with FDR Correction)

| Variable | PFDR | Cohen's d | Direction (Male − Female) |

|---|---|---|---|

| timbre_3_mean | 0.00126 | +0.374 | Male > Female |

| timbre_9_mean | 0.00253 | +0.319 | Male > Female |

| timbre_5_mean | 0.00368 | +0.314 | Male > Female |

| pitch_0_mean | 0.00499 | +0.313 | Male > Female |

| pitch_5_mean | 0.00915 | +0.291 | Male > Female |

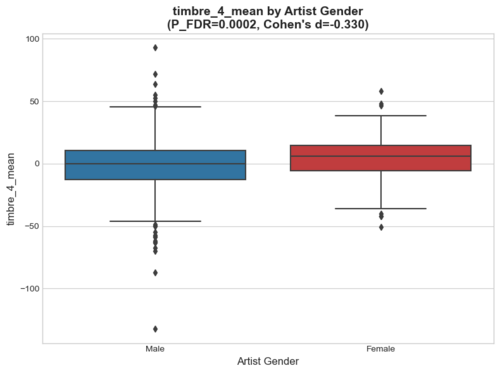

| timbre_4_mean | 0.01348 | −0.270 | Female > Male |

| pitch_7_mean | 0.01348 | +0.265 | Male > Female |

| pitch_9_mean | 0.01348 | +0.268 | Male > Female |

| pitch_10_mean | 0.02358 | +0.251 | Male > Female |

| pitch_1_mean | 0.02563 | +0.228 | Male > Female |

The largest differences are found in timbre-related features, especially timbre_3_mean, timbre_9_mean, and timbre_5_mean, which show small to moderate effects (Cohen's d ≈ 0.31–0.37). Pitch-class profile features also play a role, but with slightly smaller effects. Overall, all significant differences are small to moderate in size (|d| ≈ 0.23–0.37), suggesting considerable overlap between male and female artists despite the statistical significance of the results.

RQ2: Acoustic features associated with gender

To identify which acoustic features contribute most to gender differences, a Random Forest classifier was trained at the artist level using all 26 acoustic variables. Model performance was evaluated with 5-fold stratified cross-validation.

The model reached a mean balanced accuracy of 0.521 (± 0.077) and a mean ROC–AUC of 0.679 (± 0.126), indicating performance only slightly better than chance. The F1-score was low (0.132 ± 0.200), reflecting both the strong class imbalance and the limited separation between male and female artists in the acoustic feature space.

Table 2: Acoustic Features with the Highest Importance Scores (Random Forest Classification)

| Variable | Importance | Std |

|---|---|---|

| timbre_5_mean | 0.108 | 0.016 |

| timbre_4_mean | 0.051 | 0.009 |

| timbre_9_mean | 0.034 | 0.009 |

| timbre_8_mean | 0.024 | 0.008 |

| timbre_3_mean | 0.016 | 0.007 |

| pitch_10_mean | 0.015 | 0.006 |

| timbre_11_mean | 0.006 | 0.004 |

| tempo | 0.006 | 0.004 |

| pitch_8_mean | 0.005 | 0.003 |

| pitch_0_mean | 0.005 | 0.004 |

Timbre-related features make up seven of the ten most important variables, suggesting that spectral characteristics are the main acoustic dimensions associated with gender-related patterns. Pitch-class features and broader descriptors such as tempo play a more limited role.

The model's low classification performance, despite clear differences at the group level, points to an important distinction: statistically detectable differences do not imply reliable prediction at the individual level. Gender-related acoustic variation is present, but it is small compared to other sources of variation such as genre, artist identity, and production style.

RQ3: Genre-dependent gender patterns

To examine whether gender-related acoustic differences vary across musical genres, a two-way ANOVA was performed at the artist level on the five most significant variables identified in RQ1. The analysis was limited to genres with sufficient representation (at least 15 male and 5 female artists), resulting in a sample of 477 artists across six genres: Blues, Country, Jazz, Pop, R&B, and Rock.

Table 3: Two-Way ANOVA Results for Genre × Gender Interaction

| Variable | Gender F | Gender P | Genre F | Genre P | Interaction F | Interaction P | Significant? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| timbre_3_mean | 5.62 | 0.018 | 2.11 | 0.063 | 4.76 | 0.00030 | Yes |

| timbre_9_mean | 0.89 | 0.346 | 5.62 | <0.001 | 0.83 | 0.530 | No |

| timbre_5_mean | 6.79 | 0.009 | 14.49 | <0.001 | 0.90 | 0.479 | No |

| pitch_0_mean | 1.95 | 0.163 | 9.87 | <0.001 | 0.24 | 0.945 | No |

| pitch_5_mean | 1.58 | 0.209 | 2.49 | 0.031 | 2.05 | 0.071 | No |

The results show that only one variable (timbre_3_mean) displays a statistically significant Gender × Genre interaction (p = 0.00030). For the other variables, gender differences remain largely consistent across genres. In the case of timbre_3_mean, the interaction reflects clear variation in the size of the gender difference between genres, with the largest gaps observed in Jazz (+15.22), Rock (+4.91), and Blues (+4.44).

Overall, the analysis shows limited evidence for genre-specific gender effects. Only one of the five examined acoustic variables displays clear variation in gender differences across genres, indicating that genre moderates gender-related patterns in some cases but not systematically. More broadly, genre emerges as a much stronger source of acoustic variation than gender, shaping musical characteristics to a far greater extent.

Robustness and global structure

Two sensitivity analyses confirm the robustness of the primary RQ1 finding for timbre_3_mean. First, a balanced bootstrap procedure (n = 148 artists per gender, 1,000 iterations) yields a median p-value of 0.00151, with 97.2% of iterations statistically significant and a median Cohen's d = 0.372 [95% CI: 0.226, 0.502]. Second, exclusion of extreme outliers (>3 SD, 6 artists removed) results in an even stronger effect (p < 0.001, d = 0.400), indicating that results are not driven by a small number of influential observations.

A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on a balanced artist sample indicates that the first two components account for 22.1% and 9.4% of the total variance, respectively. Both PC1 and PC2 show statistically significant gender differences (p = 0.00075 and p = 0.00122), but the scatter plot reveals considerable overlap between male and female artists. This reinforces the conclusion that gender-related acoustic variation is a relatively minor dimension within the overall acoustic space.

Discussion and Limitations

Interpretation of findings

Across all analyses, the results indicate that gender-related acoustic differences do exist, but they are small in magnitude and strongly shaped by musical context.

At the artist level, several acoustic features differ systematically between works associated with male and female artists. About half of the tested variables show statistically significant differences, particularly timbre-related coefficients, with weaker effects for pitch-based features. However, the effect sizes are small to moderate, meaning that the distributions of male- and female-associated music largely overlap. These differences reflect subtle shifts in average tendencies rather than clear-cut acoustic categories.

This subtlety is confirmed by the classification results. Although the Random Forest model performs slightly better than chance, its predictive power remains low. In practice, this means that gender cannot be reliably inferred from acoustic features alone. Still, the model consistently relies most on timbre features, which aligns with the univariate findings. The contrast between statistical significance and weak prediction highlights an important point: group-level differences do not necessarily translate into accurate individual-level classification. In musical data, gender-related signals are present but are easily outweighed by other factors, such as genre, artist identity, and production choices.

Finally, genre plays a moderating but secondary role. Interaction effects between gender and genre are rare, indicating that most gender-related acoustic differences are relatively stable across styles. When moderation does occur, its strength varies by genre, with somewhat larger differences observed in Jazz, Rock, and Country. Nevertheless, genre main effects are consistently much stronger than gender effects, confirming that stylistic context is the primary driver of acoustic variation.

Overall, these findings suggest that gender-related acoustic patterns in music are real but weak. They are best understood as one minor dimension within a much richer acoustic and stylistic landscape, rather than as a defining or predictive characteristic.

Quality assessment

Several analyses support the overall quality and internal consistency of the dataset and results. The Genre Distribution Comparison plot shows that the 10,000 song subset closely mirrors the full dataset in terms of genre representation, with minor deviations in specific genres like Rock and Pop_Rock. This alignment suggests that the subset is representative of the broader Million Song Dataset (MSD) in terms of genre diversity.

The Timbre Mean Comparison and Pitch Mean Comparison plots further validate the subset’s representativeness. While the subset of 10,000 songs is compared to 94,482 songs [9], the trends in timbre and pitch means are largely consistent between the two. The timbre and pitch features in the subset closely follow the patterns observed in the other dataset, with only minor deviations in specific dimensions ( timbre_1 and pitch_3). This consistency reinforces the reliability of the subset for exploratory acoustic analysis.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) results indicate that the first two components explain 20.5% and 9.2% of the total variance, respectively, and both exhibit statistically significant gender differences. However, the strong overlap between gender groups in the PCA space suggests that gender explains only a small fraction of the global acoustic variance. This aligns with the Gender Distribution Comparison plot, which shows a similar distribution of male and female artists in both the subset and the full dataset [10], further confirming that gender-related acoustic differences are subtle and not definitive.

The Top 10 Countries Distribution Comparison plot reveals that the subset maintains a similar geographic distribution to the full dataset, with the US being the most dominant country in both. This geographic consistency supports the subset’s representativeness and reduces concerns about sampling bias related to regional musical styles.

Limitations

Despite these strengths, several limitations constrain the interpretation and generalizability of the findings. The dataset’s temporal coverage, spanning from the 1960s to the early 2010s, limits its applicability to contemporary music production. Since the early 2010s, changes in production technologies, distribution models, and industry structures (such as the rise of streaming platforms and home recording) may have altered how gender-related patterns manifest in acoustic features. The findings should therefore be understood as characteristic of the historical period represented in the MSD rather than reflective of current musical practices.

Geographic and cultural biases further restrict generalizability. The Top 10 Countries Distribution Comparison plot highlights the dominance of artists from North America (particularly the US) and Western Europe in both the subset and the full dataset. This geographic concentration means the results are most applicable to Western popular music traditions. Musical practices in other cultural contexts may follow different aesthetic norms, production conventions, and gender dynamics, which are not captured in this dataset.

Genre imbalance represents another constraint. The Genre Distribution Comparison plot shows that Rock, Pop, and Pop_Rock are heavily overrepresented, while genres like Hip-Hop, Electronic, and non-Western traditions are underrepresented. Although stratification and weighting strategies were applied, this imbalance limits the ability to draw robust conclusions about underrepresented genres. Genre concentration may also interact with gender distributions, as some genres have historically exhibited pronounced gender imbalances.

Limitations in gender metadata are particularly significant. The Gender Distribution Comparison plot reveals that approximately 54% of tracks in the subset lack gender information, reducing the effective sample size for gender analysis. The binary encoding of gender (Male/Female) does not capture the diversity of gender identities, and the pronounced class imbalance between male and female artists further constrains statistical power and model robustness.

From an inferential standpoint, the study’s descriptive and exploratory design precludes causal claims. While genre was controlled for and analyses were conducted at the artist level, the results document associations rather than causal mechanisms. Multiple explanations may underlie the observed patterns, including unequal access to production resources, gendered differences in musical training, genre segregation driven by industry gatekeeping, disparities in professional networks, and stylistic choices shaped by market positioning. The absence of contextual data on production environments, training backgrounds, and career trajectories limits the ability to evaluate these mechanisms directly.

Finally, the findings have implications for music information systems that must be interpreted cautiously. The weak predictive accuracy and substantial overlap in acoustic space, as seen in the Timbre Mean Comparison and Pitch Mean Comparison plots, suggest that gender-related acoustic variation is dominated by genre, artist style, and production context. Algorithmic biases in recommendation systems are therefore more likely driven by collaborative filtering, historical listening patterns, and feedback loops than by acoustic similarity alone. Nonetheless, even weak acoustic signals may interact with other bias sources or be amplified through iterative recommendation processes, particularly given the central role of timbre features in content-based models.

All interpretations must be framed ethically. The observed acoustic differences are not understood as intrinsic or biologically determined but as outcomes of social, stylistic, technical, and professional processes shaped by structural inequalities in the music industry. The analysis does not support essentialist interpretations of gender and should not be used to justify gender-based categorization or inference. Instead, it highlights the importance of addressing inequality at its structural roots rather than through acoustic proxies.

References

- ↑ Smith, S. L., Choueiti, M., & Pieper, K. (2023). Inclusion in the Recording Studio? Gender and Race/Ethnicity of Artists, Songwriters & Producers across 900 Popular Songs from 2012-2020. USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative.

- ↑ Smith, S. L., Choueiti, M., & Pieper, K. (2018). Inclusion in the Recording Studio?. USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative.

- ↑ Wang, A., & Horvát, E. (2019). Gender differences in the global music industry: Evidence from MusicBrainz and the Echo Nest. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 13, 517-526.

- ↑ Hesmondhalgh, D., & Baker, S. (2015). Sex, gender and work segregation in the cultural industries. The Sociological Review, 63(1_suppl), 23-36.

- ↑ Schedl, M., Zamani, H., Chen, C. W., Deldjoo, Y., & Elahi, M. (2018). Current challenges and visions in music recommender systems research. International Journal of Multimedia Information Retrieval, 7(2), 95-116.

- ↑ Vall, A., Dorfer, M., Eghbal-zadeh, H., Schedl, M., Burjorjee, K., & Widmer, G. (2019) Feature-combination hybrid recommender systems for automated music playlist continuation. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction, 29(2), 527-572.

- ↑ Ferraro, A., Bogdanov, D., Yoon, J., Kim, K. S., & Serra, X. (2021). Artist and style exposure bias in collaborative filtering based music recommendations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.13972.

- ↑ Bertin-Mahieux, T., Ellis, D. P., Whitman, B., & Lamere, P. (2011). The Million Song Dataset. Proceedings of the 12th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR), 591-596.

- ↑ Bal, A. (2018). Human Learning and Decision Making. Master's thesis, Tilburg School of Humanities and Digital Sciences.

- ↑ MusicBrainz. (n.d.). MusicBrainz Statistics. Retrieved from MusicBrainz.

Credits

Course: Foundation of Digital Humanities (DH-405), EPFL

Professor: Frédéric Kaplan

Supervisor: Alexander Rusnak

Authors: Camille Dupré Tabti, Olivia Robles

Date: December 17, 2025

GitHub Repository: https://github.com/camilledupr/FDH-project

Acknowledgments: This project uses a subset of the Million Song Dataset created by Thierry Bertin-Mahieux, Daniel P.W. Ellis, Brian Whitman, and Paul Lamere. Gender metadata was enriched through the MusicBrainz API. We thank the computational music analysis community for methodological foundations.