Language-Based Agent: Simulation of Venice, circa 1740

Executive Summary

Problem: Historical records resemble an "information mushroom": data is dense in the present but thins into a sparse 'stalk' in the past. While LLMs can theoretically bridge these gaps via interpolation, they often generate unstable, unverified "Simulacra" rather than plausible history."

Operational Objective: To develop a pipeline that (1) densifies fragmentary travel narratives (Venice c. 1740) into rich, immersive scenes, and (2) verifies this output using a secondary LLM layer to enforce coherence against primary sources. We measure not only output quality, but most importantly system behavior: evaluator reliability, grounding quality, revision dynamics, protocol sensitivity, and failure modes.

Scope: Textual enrichment of specific micro-historical events (Goethe 1786; De Brosses 1739). Development of general protocol that can scale to other tasks and future models, evaluation of current trends and exploration of failure cases.

Our analysis indicates that despite the inherent statistical volatility of the evaluation mechanism and the sensitivity of resource integration, a structured, step by step generation protocol provides the most stable framework for historical reconstruction using Gemini 2.5 Flash.

Qualitatively (but in an inconsistent way), the system demonstrates a validated capacity to densify sparse historical records into immersive, evidence-based narratives, successfully distinguishing plausible, grounded reconstruction from unverified interpolation.

Ultimately, this project validates the developed platform as a scalable, reproducible laboratory that isolates protocol performance from model-specific limitations, establishing a rigorous foundation for the future of automated historical simulation.

Introduction and Motivation

Large Language Models (LLMs) can now generate fluent, immersive historical prose on demand. For Digital Humanities, the bottleneck is no longer syntactic quality, but epistemic control: how to keep generated content constrained by the historical record and transparently auditable.

At the same time, LLMs are attractive precisely because they behave like an imperfect latent world model. They compress large amounts of textual regularities about places, institutions, material culture, and social scripts. We could consider the LLMs as simulators, where the prompt is the original seed that conditions this latent model, and where generation samples a concrete narrative trajectory. This makes it possible to propose plausible reconstructions in areas where historical evidence is non-existent. However, the same mechanism also drives failure: sampling optimizes for what is probable in the learned distribution, not for what is warranted by the specific sources at hand.

Reusing the central allegory used during the lectures, the past can be represented as an information mushroom: dense documentation in the cap, and a thin, discontinuous stalk as we move backward in time. In this setting, an LLM can “fill the blur” by interpolation, but the result is typically a simulacrum: a plausible narrative instance that remains unstable under scrutiny. What historians, curious people, and educators need instead is a simulat: a narrative reconstruction that remains stable enough to be checked, debated, and iteratively improved against explicit constraints.

Until now, standard LLMs were generating text as a continuous stream. In that mode, it cannot naturally stop to verify claims, consult a map, cross reference a source, or reconcile conflicting evidence. We refer to this limitation as the missing pen lift mechanism: the inability of the model to pause its stream of thought to verify facts, much like a writer who never lifts their pen to check a reference. We are starting to see evolutions with agentic frameworks that include initial and intermediate thinking, tool use like web-search, RAG...

Project evolution during the semester

Phase I: exploratory simulation prototypes

We began with the “video game” paradigm to probe what-2025 era LLMs make easy:

- Agent simulation on a 2D map (See appendix): agents that move, talk, and keep short term state. They are in a well-defined historical context and are supposed to interact in the "historical" way, the goal is to study social life and evolution on a small case. You can find and play the prototype here.

- 3D interaction prototypes (See appendix): immersive navigation and dialogue with historical agents. Similar to the previous one, but with better modalities (3D, voice to voice) and the user becomes a character of the simulation that can interact easily. You can find our prototype here.

- Time-machine-style exploration (See appendix): selecting a place and date to generate a scene. Demonstrating the ability to interpolate any place anytime. This would be one of the ultimate past data augmentation, but is demonstrating serious limits when sampling beyond the scope of well known events. App link.

- Event graph extraction and augmentation prototype (See appendix): a prototype to upload a travel text and structure it into a graph of events with time information, people present or mentioned, and the event location. The interface then allows targeted enrichment of a selected event, extrapolation of missing attributes, and generation of events in between two known events, with a clear visual separation between information extracted from the source text and information generated by the model. App link.

These prototypes demonstrated immersion, but they were methodologically weak. They produced speculative interactions, that is Simulacra (unstable trajectories), without a mechanism to stabilize them into Simulats (consensual, stable objects) that remain coherent with sources. The outputs were often convincing, but not scientifically inspectable.

The main value of these early prototypes is to demonstrate the potential of the medium. Systems of this kind would have been unrealistic a few years ago, while today we can implement serious prototypes quickly.

A broader question remains open and is not answered in this report: the purpose of such simulations. What would we do with them, and which historical or pedagogical questions will they answer. This uncertainty is one reason we shifted from building a "cool simulation" to building an evaluation framework and a reproducible laboratory.

Phase II: Midterm proposal and evolution from it

At midterm, we reframed our early simulation prototypes into a method to enrich 18th century Venice travel narratives with historically grounded context (see midterm prototype in the appendix), with an emphasis on capturing the Zeitgeist and incorporating iconographic and iconological interpretations. The planned pipeline was generator centered and intentionally simple: manually extract an event from a travel story, generate an enriched scene, ensure continuity with the surrounding narrative, optionally add context documents, and inspect outputs in a lightweight interface. Evaluation was central from the start, but it targeted the initial ambition of producing nice, historically accurate, plausible scenes, and used broad quality criteria: narrative coherence and thematic fit, historical period accuracy and social authenticity, plausibility, and readability, assessed both by us and by an LLM. Methodologically, we also proposed multiple “levels of simulation” (event only, whole travel story, model generated context, external documents). First prototype available here.

We revised these criteria because the added detail that makes densification valuable is precisely what lacks ground truth. For many invented additions, we cannot reliably decide what is historically accurate, and even informed readers can disagree about plausibility, authenticity, or high level cultural frames (Weltanschauung, Zeitgeist, Alltag). Readability is subjective and can reward better prose at the expense of constraint compliance. These limits push evaluation toward impression-based judgments. We therefore shifted to what we can actually test and audit: coherence. Coherence is checkable because it supports explicit linkage: one can highlight a claim in the generated text, point to a provided resource or to earlier assertions, and demonstrate incompatibility. In the final project (see final prototype in the appendix), evaluation is mostly defined as coherence under explicit constraints that can be audited against what the model was given and what it already asserted.

This change also simplified the experimental design. Instead of broad coverage across many stories, events, and contextualization levels, we reduced combinatorial exploration and anchored the work around two well defined nodes with bounded document sets, so that failures remain interpretable and we can become expert in the constraints of each scene. What expanded instead is the methodological layer: we developed a wider set of generation and evaluation protocols and made the bonus direction of iterative evaluation and revision a primary focus, supported by instrumentation and reproducibility in FDHSim.

As a result, the report’s results are not framed as “text quality improved” in isolation. They are framed as measurements and explanations about system behavior: how reliably the model critiques its own outputs, how revision behaves across iterations (including progress, regressions, and oscillations), how protocol choices change failure patterns, and how often the system follows or breaks the interface assumptions, complemented by concrete case fragments that help explain why divergences occur.

What remained constant across midterm and final is the backbone: travelogue based reconstruction (Goethe and De Brosses) and a resource aware approach to densifying events for a new kind of historical reading. What changed is the claim and the method: from judging realism and plausibility to auditing coherence constraints, and from a generator centered prototype to a reproducible laboratory that makes generation, evaluation, grounding, and revision traceable.

Case study and scope

We ground the project in two tightly bounded “nodes” extracted from travel narratives, chosen to maximize constraint clarity and interpretability of failures.

- Goethe in Venice (3 October 1786): an itinerary across sites where perception, material details, and performance matter.

- De Brosses in Venice (14 August 1739): an institutional scene (Grand Council election) where procedure, roles, and crowd dynamics matter.

These nodes are not only inputs for narrative generation. They are deliberately designed as small test beds for model behavior under constraints: each contains, we hope, checkable dependencies across time, space, procedure, and wording, while remaining short enough for manual auditing.

Scope choices are deliberate:

- We focus on micro-historical scenes (on the order of a few pages) so that both humans and the system can audit them end to end.

- We limit to two nodes to become expert in their constraints and make anomalies interpretable.

- We do not claim historical truth for invented details. Our claim is narrower: we test whether the system can remain coherent with the resources it was given and with its own prior assertions.

- Because the pipeline includes evaluation and revision, the same nodes also support model evaluation questions, not only generation: evaluator reliability and variance across repetitions, grounding quality (can the system point to evidence for key claims), revision dynamics across iterations, and sensitivity to context packing and prompting.

We frame historical reconstruction as a constraint satisfaction problem requiring simultaneous adherence to distinct coherence vectors: internal narrative continuity, fidelity to primary fragments and the provided additional resources, and strict spatiotemporal feasibility.

An ideal solution would encode constraints in a symbolic system and verify them against a formal representation of the sources. That remains out of scope here. Instead, we test an imperfect but scalable proxy: using the LLM itself in a recursive loop to critique and revise its outputs under explicit constraints.

Operationally, we split the process into two roles:

- System 1 (generation) produces an initial narrative draft. We will refer to this system as the “generator”.

- System 2 (evaluation and revision) critiques incoherencies against the provided sources and forces a rewrite. We will refer to this system as the “evaluator”.

The core research question is not “Can the model generate good text?” but “What is current state of the art”, knowing that things will evolve but what is possible today will probably continue being possible: “Under which protocols does the model become more coherent with the evidence it was given, and how stable are those improvements?”, “What are typical failures of the model and how can we explain them?”

Related work and positioning

Recent research has documented that hallucination is a persistent failure mode of LLMs, especially when the task invites open ended completion. A common mitigation strategy is retrieval augmented generation, where generation is coupled with a retriever over external documents. Another line of work shows that test time loops can improve outputs without changing model weights, by having the model critique and refine its own drafts or reflect on errors across trials. In parallel, LLM based evaluation has become attractive because it scales, but it is also known to suffer from systematic biases and instability.

Within Digital Humanities, these observations converge on a practical requirement: if generative systems are used as research instruments, their workflows must be documented and their outputs must be inspectable. Our project positions itself at this intersection. We do not claim to solve historical truth in the strong sense. We focus on a narrower and testable objective: making densified historical narratives more auditable by enforcing coherence against explicit resources, recording the full generation context, and studying how protocol choices affect stability.

What this project contributes

This project proposes a pragmatic middle layer between free form generation and formal symbolic verification: a reproducible workflow where coherence constraints are explicit, critique is structured, revisions are traceable, and failures are studied as first class results. Our project does not introduce a symbolic logic engine to solve this (which remains the “ideal” gold standard but out of scope); rather, we attempt to approximate Articulated Reasoning by using the LLM itself in a recursive loop to enforce historical constraints, namely coherence with the data we have. We are testing an imperfect bridge: using a probabilistic system to police its own coherence against rigid historical sources.

Concretely, we instantiate this workflow with Gemini 2.5 Flash under our prompts and resource packs. These results should be read as behavior measurements in a controlled setup, not as a timeless evaluation of a specific model. Because model versions change quickly, FDHSim is designed as a rerunnable test bench: the same protocols can be executed on newer models with minimal changes, making it possible to compare model families over time.

A second contribution is failure analysis. Beyond aggregate trends, we document and interpret divergence cases (for example reward hacking responses to repeated fidelity critiques, evaluator instability, instruction noncompliance, abrupt style drift, and sensitivity to context packing and sampling). We treat these anomalies as informative and propose mechanism level explanations grounded in prompt structure, long-context limitations, and the separation between generation and critique.

The intent is not to claim that an LLM can “know history,” but to test which scaffolds make probabilistic generation more auditable and more useful for historical inquiry.

Deliverables

- FDHSim (the laboratory application)

- A general, web-based environment (React and TypeScript) for controlled generation, evaluation, grounding, and iterative revision under explicit resource constraints. The same interface supports tools for checks of evaluator reliability, grounding quality, revision dynamics, and consistency across repeated runs.

- A reproducible test bench: each run records prompt snapshots, enabled resource sets, protocol parameters, document lineage, diff statistics, and token telemetry so experiments can be rerun and compared across model versions.

- Exportable audit dossiers (HTML and JSON) that preserve the full context, intermediate artifacts, and results needed to review or replicate each output outside the app.

- This laboratory application could be used well beyond the project and is fully customizable; it is a powerful tool for prompt engineering.

- You can see the full description in appendix.

- GitHub repo access here.

- Venice corpus of generated reconstructions

- For each node: initial drafts, structured critiques, grounded evidence extracts, and refined versions. You can access all the AI generated stories.

- Version trees that make iterative change traceable.

- Protocol analysis and results

- Direct generation vs step by step generation vs refinement loops.

- Convergence and regeneration trends, including failure modes and special cases (reward hacking, evaluator instability, protocol breaking).

- Context ablation and consistency experiments to probe dependence on resource volume and prompt sensitivity.

- Evaluator evaluation.

- Presentation slides

- Slides access here.

Resources and event description

What events will we enhance

We anchor the early project description in two “nodes” built from travel narratives. Each node has (1) a travel story, (2) one event we simulate as a compact scene, and (3) an external resources document, based on historical sources.

The external resources (3) are all primary sources, and are processed by Gemini 3 Pro in order to produce a synthetic document for our generator. The model was prompted to provide a synthetic historical context for a story enhancement process using LLMs. It knew which event would be enhanced: the provided resource document focused only on the context of the simulated events, in order not to be too large (and also in order that we can have a sense of their content).

First node: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Italian Journey, 1816

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Italian Journey (1) was first published in 1816. This travel story depicts his travels in Italy between 1786 and 1788. He arrives in Venice as a careful observer who cross checks what he sees with what he has read. The travel frame is his observation of the city as a sequence of visits where architecture, materials, and performance are inspected rather than simply admired.

We will focus our simulation on a particular excerpt depicting part of his activities during the 3 October 1786 (2). We chose this particular extract because it consists of multiple checkable micro-scenes. This extract has a lot of spatial movements which are not explicitly detailed, and we thought it would be interesting to see if the system could bridge those gaps. Here are the 3 locations explored in the extract:

- Il Redentore (Giudecca): inspection of the church attributed to Palladio.

- A walk along the Riva degli Schiavoni: a short walk with some observation of Venetian activities.

- Ospedale dei Mendicanti: a musical performance of an oratorio in a church.

Documents used to constitute external resources for this node and what they contribute (3):

- Volkmann, Johann Jacob, Historisch-kritische Nachrichten von Italien, 1777–1778: a guide book that Goethe is referring to during his travel story.

- Palladio, I Quattro Libri dell’Architettura, 1570: a reference set of books for theory of architecture already at the time. Goethe also knew those volumes well. He refers to them in the text in the Il Redentore part.

- Goldoni, memoirs, 1787: some parts can be used during the walk, for street level layer information, to set the tone of dialogue.

Second node: Charles de Brosses, Lettres familières écrites d’Italie, 1858

Charles de Brosses was a French politician and man of letters. He traveled to Italy between 1739 and 1740. The letters he wrote were compiled into multiple books, which are known for the author's sometimes comical, cynical tone. In his Lettres familières écrites d’Italie (1), he describes Venice through institutions, social behavior, and procedural detail. The specific event (2) we will be using here is his attendance, as an observer, at the Grand Council in Venice on 14 August 1739.

We chose this event because it forces a simulation to represent procedural steps and crowd behavior. We also wanted to compare how the system could improve more in detail in a single longer event, rather than a succession of smaller parts, as for Goethe’s chosen extract.

Documents used to constitute external resources for this node and what they contribute (3):

- Amelot de La Houssaye, Abraham-Nicolas, The History of the Government of Venice. English Edition, 1677: This document, even if written 60 years earlier, is an important source about the procedural political system of Venice at the time. Most of its content should still be relevant to enhance de Brosses’ story of the Grand Council.

Our two nodes provide two contrasted events, for which we hope to make different observations. In summary:

- Goethe (1786): compact, multiple smaller scenes, with spatial displacement, about the city, architecture, artworks.

- De Brosses (1739 to 1740): institutional scenes where procedure, social stratification, and crowd interaction matter.

Summary of the chosen methods

Description of Methods and Technical Choices

The following section details shortly and with some examples the decisions regarding context management, model selection, prompt engineering, and resource curation, acknowledging that these choices constitute specific variables within a larger experimental space. In order to make this wiki more digestible, the entire prompt description and the app description is available in the appendix.

Context Management: Full Context Injection vs. RAG

The primary challenge was providing the model with access to historical resources to constrain generation. We evaluated three architectures:

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): While scalable, RAG relies on semantic similarity search (embeddings). We rejected this because historical nuance often lies in the absence of information or in global narrative flow, which chunk-based retrieval fractures. RAG risks retrieving facts without their "connective tissue," leading to a patchwork narrative. Furthermore, the volume of our specific dataset did not justify the overhead of vector database implementation.

- Logic-Based Verification: Converting text to symbolic logic (e.g., Knowledge Graphs) to mathematically verify consistency. While ideal for "Simulats," this was deemed out of scope due to the complexity of translating narrative nuance into formal logic without losing the "Zeitgeist" texture.

- Full Context Injection (Selected Method): We utilized the large context window of Gemini 2.5 (up to 1M tokens) to inject all relevant resources directly into the prompt.

- Justification: This mimics a historian's workflow: "reading the table" rather than "querying a database." It allows the model to perform attention over the entire corpus simultaneously, enabling the detection of subtle cross-reference contradictions (e.g., a character being in two places across different documents) that RAG might miss.

- Trade-offs: This approach is computationally expensive and introduces "Lost in the Middle" risks (where attention fades in the center of the prompt). However, for our specific nodes (~50k–100k tokens), it provided the necessary fidelity resolution.

Model Selection: The Single-Model Baseline

We selected Gemini 2.5 Flash via Google AI Studio as the engine for both generation and evaluation. We deliberately chose not to use a superior model (e.g., GPT-5.2 or Gemini 3 Pro) to evaluate a smaller model. This is because using a "smarter" evaluator would measure the difference in model knowledge, not the efficacy of the method. By using the same model to evaluate itself, we isolate the Refinement Loop as the variable. If Gemini Flash can correct a hallucination it just generated, it proves that the architecture (separating Generation System 1 from Evaluation System 2) enables self-correction, independent of the model's raw parameter size. In the end, this choice was also pragmatic, leveraging the high rate limits and long context window available for quicker extensive iterative testing.

Prompt Architecture and Evolution

The project moved from simple natural language prompts to a modular "System Prompt" architecture.

- The Generator Persona: The model is framed not as a creative writer but as a "Historical Simulation Engine." We explicitly banned "literary flourishes," "modern adjectives," and "empty wording" to force concrete, Alltag-focused description.

- The Evaluator Stance: Early tests showed the model's tendency toward sycophancy (rating its own output highly). We evolved the prompt to be strictly negative: "Focus ONLY on what is wrong. Do not make positive comments." This negative-only constraint was necessary to break the "laziness" of the model and force high-granularity critique.

- The Refinement Instruction: A closed-loop prompt that receives the negative critique and the original draft, instructed to "rewrite the narrative to resolve the critique without altering valid historical data."

Generation Methods (Protocols)

We designed the FDHSim application to switch between three distinct generation architectures to compare their efficacy.

- Direct Generation: Zero-shot generation based on resources. This serves as the baseline (the "Simulacra"), reflecting the model's raw probabilistic instinct.

- Step-by-Step (Articulated Reasoning): The model is forced to output a thought block before every text block. This approximates reasoning by forcing the model to plan and check constraints before committing to narrative text. Concretely in our case, the text is generated paragraph after paragraph.

- Refinement Loop: After being evaluated, a certain text and its related comments are used to generate a new, in theory improved text. The resulting text can then be again evaluated and regenerated, repeating that process each iteration.

Micro-Decisions and Influence Factors in prompting

Beyond the major architectural choices, we acknowledge several specific technical decisions that define the experimental boundary conditions. While not individually justified in depth here, each acts as a variable influencing the results, for example:

- Language: conducting the simulation in English (for accessibility and analysis) rather than period-accurate Italian or French.

- Narrative Voice: enforcing a First-Person perspective to test immersion constraints vs. a Third-Person objective view.

- Resource Normalization: using raw text vs. structured/cleaned data, and the specific hierarchy assigned to conflicting sources.

- Feedback Modality: using continuous scores (0–100) and text comments rather than binary Pass/Fail metrics.

- Sampling Parameters: decisions regarding Temperature and Top-K settings to balance creativity with adherence.

- Event Granularity: limiting generation to ~3 pages to ensure human verification remains feasible.

Results and analysis

Evaluation of LLM-Generated Critiques

To assess the reliability and relevance of the LLM as an evaluator, we first examine the taxonomy of its feedback. The model was tasked with identifying weaknesses within the generated text and to suggest negative critical feedback across specific dimensions. Following an iterative trial-and-error process, we established four distinct evaluation criteria:

- Respect of the Initial Text (RIT): This criterion assesses alignment with the initial event and the overarching travel story. The prompt instructs the model to flag added information only if it explicitly contradicts the source material. Conversely, inventions absent from the initial event are permissible, provided they remain plausible within the context.

- Narrative Quality (NQ): This evaluates the flow and style of the text. The prompt targets unnatural phrasing, such as excessive literary flourishes, disjointed facts ("patchwork"), narrative gaps, or a lack of necessary exposition for an uninformed reader.

- Historical Coherence (HC): This assesses alignment with the context and Zeitgeist of 18th-century Venice. The model is instructed to verify if the augmented parts are consistent with general historical knowledge and provided resources. A critical constraint is applied: details explicitly present in the event source material must be treated as factual, even if they contradict external historical knowledge or the provided resources.

- Spatial and Temporal Coherence (STC): This verifies alignment with the chronology of the whole travel story, not just the augmented event. Additionally, it checks if the spatialization in the augmented segments matches the geography described in the event source material.

To gauge the capacity of the evaluator, we proceed in three steps: a quantitative analysis of scoring consistency, a case study on error detection and a short non-exhaustive list of successes and errors made by the evaluator throughout our experiment. This will in the end lead to a qualitative review of feedback relevance. This assessment is crucial for validating the "Refinement Loop" generation method, which relies heavily on the evaluator’s accuracy.

Quantitative Assessment: Scoring Consistency

Before assessing the qualitative relevance of the generated critiques, we evaluated the stability of the LLM’s scoring mechanism. Given the non-deterministic nature of Generative AI, it is crucial to determine whether the evaluator applies criteria consistently across identical inputs.

We selected two control texts—simulated events of De Brosses’ travel story—and subjected them to the evaluation prompt 20 times each under identical conditions (temperature, context, and instructions).

- Text A: A generated event without access to external resources.

- Text B: A generated event with access to resources.

Analysis of Volatility

It is important to note that Text B (With Resources) was selected because it contained a blatant hallucination: based on a misinterpretation of resources, characters were described as wearing heavy fur coats in summer. This significant error was consistently flagged across the 20 iterations. This partly explains the lower mean score for Historical Coherence (71.5).

However, the analysis reveals significant volatility in the scoring output. As seen in Graph 1, scores for Respect of Initial Text varied by as much as 45 points (55 to 100) for the exact same text. In Graph 2, the Total Score fluctuated between 76.3 and 91.5. This result is particularly surprising given that the majority of the substantive content of the critiques—the "fur in summer" mistake—was the same. It is in fact the only comment in the “best” and also in the “worst”, with the only difference that in the worst, it is rephrased two times in two different categories (RIT and STC). This suggests that the numerical score is often in a large manner correlated with the number of comments generated in a specific run rather than a deterministic evaluation of quality.

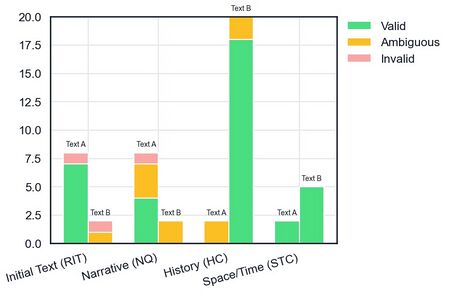

Qualitative Assessment: Validity of Feedback

Given the volatility of the numerical scores, we established a tripartite classification system to grade the relevance of each unique comment generated during the trials:

- Valid (Pertinent): The comment identifies a factual error, a logical inconsistency, or a genuine stylistic weakness. The critique is accurate and actionable.

- Ambiguous (Indeterminate): The comment lacks clarity, is partially correct but misapplied, or depends heavily on subjective interpretation without sufficient evidence.

- Erroneous (Invalid): The comment is factually incorrect, irrelevant to the context, or constitutes a "hallucination" where the model fails to follow the prompt.

Findings

In both scenarios, "Invalid" comments represent approximately 10% of the output. The distribution highlights two distinct behaviors. In the case of Text B, the high number of valid Historical Coherence comments (18) and Spatial and Temporal Coherence (5) corresponds to the repeated identification of the "fur coat" error. Conversely, for Text A (Without Resources), the model produced a wider variety of comments with a lower density (mean of 1 comment per evaluation), occasionally repeating the exact same critique across iterations.

A few examples of output in regards to consistency

We now will go through 3 examples that we found during our research, and that we think are relevant to speak about the evaluator consistency.

The Ability to Prioritize Source Material

The evaluator demonstrates a strong capacity to resolve conflicts between external historical resources and the primary source text (EVENT). A clear example of this occurred regarding the description of a specific palace. While the provided RESOURCES described the building as "imposing and refined," De Brosses’ source text characterized it as "bleak" and "in the worst taste." In instances where the generator erroneously favored the external resource description, the evaluator consistently flagged this discrepancy (detecting it in 6 out of 20 trials). This suggests the model is generally effective at enforcing the hierarchy of sources defined in the prompt.

Inconsistency in the use of criteria: The Fur Coat in Summer example

This example of hallucination, present in Text B and presented above, is also useful to show the looseness with which the evaluator uses criteria: out of 20 times where the mistake was appropriately detected, the mistake was classified 13 times in Historical incoherence, 2 times in Spatial and Temporal Coherence, 4 times it was in both, and 1 time in both Narrative quality and Historical Coherence.

This variety of classification shows that the LLM can find ways to classify a mistake in multiple criteria, but also that in our case it’s really inconsistent with its classification. This could nevertheless be related to a lack of clarity in our prompts, and it raises the question of whether criteria should even be used in the future.

Outliers: Complete failure or misinterpretation

A few times during our experiments the evaluator hallucinated, leading occasionally to strange results, or even unusable comments. A simple example is the evaluator forgot that it had to only make negative comments, leading to a large amount of positive comments that the refiner can’t use in the expected way.

Another example of an outlier (with less impact) was found during the experiments on Text A. The system output 4 comments only on narrative quality, which is an abnormally large number for this kind of comments on this specific text. This specific outlier can still be used by the refiner, as all comments are either ambiguous or good.

On the 40 trials made on text A and B, we only had one of those outliers, which makes them fairly uncommon. They still are hard to avoid and could disrupt the flow of a refinement loop if not looked for.

Evaluator’s consistency conclusion

The evaluation process reveals a dichotomy in the LLM's performance. On one hand, the scoring mechanism is highly volatile, rendering the raw numerical grades unreliable as a standalone metric. The criteria are only used as blurry outlines and one concrete comment could pass from one to the other between iterations. This could certainly be mitigated through refining the prompts, or lowering the number of criteria.

On the other hand, even if not consistent between trials, the textual feedback is mostly pertinent; apart from isolated hallucinations and a 10% error rate, the majority of comments point to valid, or at least ambiguous issues. Therefore, while the evaluator is inconsistent in how much it penalizes a text, it remains a valuable tool for identifying what needs to be corrected. In the end its capability to detect errors should increase if multiple evaluations are done. With this in mind, it should still be possible to make a refinement loop process that improves generated texts, which we’ll discuss later.

Influence of the resources

As explained before, external resources were either provided or not provided to the LLM during all processes (generation with all methods and in evaluation) (see chapter ?). In this chapter, we evaluate the influence of such resources, focusing on the quality of the generated texts. A relevant statistical comparison is not possible in this chapter due to the non-identical nature of the evaluators used for texts generated with and without resources, which unfairly penalizes texts originating from different source data. Therefore, we will only be able to perform a qualitative analysis. We will present specific examples that we find most interesting regarding this matter and try to empirically identify some tendencies. We will first proceed by looking at de Brosses’s generated text and then looking at Goethe’s generated texts, as the outcomes are not the same.

Influence of Resources on Charles de Brosses’ Event

The external resources provided for Charles de Brosses’ event are highly descriptive and formatted as fragmented notes or bullet points. They primarily detail the physical setting of the events and the procedural aspects of the Grand Council, lacking complete sentence structures.

Successful Integration of resources

In the texts generated for De Brosses, the model frequently integrates the physical attributes of the location effectively. For instance, the paragraph found in Text B (discussed in the Consistency Chapter) is directly derived from these resources. This descriptive layer adds valuable spatial context to the travel story. Crucially, because the source material is structured as short, dry bullet points, the generator is forced to perform a significant amount of rephrasing and syntactic construction. As we will observe, this "forced reconstruction" often leads to better integration than when the model simply copies literary phrasing, as was the case with Goethe.

Influence of the resources on texts regarding Goethe's event

In contrast, the resources provided for Goethe’s event possess a distinct literary style. They contain pre-written descriptions of the weather, specific locations, and insights into the events he witnessed, often sourced from guidebooks (e.g., Volkmann) or other literary accounts. The inclusion of the resources in the generated texts is less refined than in de Brosses’ text. For this reason, we will focus on identifying what makes the generated texts about Goethe less relevant than with de Brosses.

Errors due to wrong understanding of hierarchy of resources

A recurring error occurs when the generator allows information from the external resources to erroneously override the facts established in the primary source event. A prominent example is the "Fur in Summer" mistake (discussed in the Consistency of Evaluation section). Here, the generator ignored the temporal context of the source event (Summer) and hallucinated that characters were wearing heavy coats, a detail lifted directly from a resource describing winter attire. Because this error was egregious, it was systematically identified by the evaluator. Our analysis suggests that these "hierarchy violations"—where the model fails to prioritize the primary event over secondary resources—are typically detected and corrected during the refinement process.

Our hypothesis to explain why we did not find any mistake in this generated text for de Brosses’ travel story is certainly explained by the differences in size of the provided resources. As Goethe’s text flows from place to place, the resource is much larger (29,000 characters against 11,000).

Tone Clashes and Empty Augmentations

A more subtle issue arises regarding the tone of the integration. When generating texts with resources for Goethe, the inclusion of external data often feels forced or stylistically jarring.

- The "Blustery Sirocco": Many texts generated with resources open by mentioning "a blustery sirocco." This phrasing is a verbatim copy from the provided resource, which the model inserts without adapting it to the surrounding narrative flow, or Goethe’s tone. To cite it from the generated text: The morning of October 3rd dawned with a blustery sirocco, a wind that carried the damp, briny scent of the lagoon into my narrow canal-side room.

- “The Famed seventeen steps, which Volkmann meticulously counted, [...]": Similarly, texts almost systematically include a reference to the "seventeen steps" leading to the church of Il Redentore (a detail from the Volkmann guidebook). To cite it from the generated text: The famed seventeen steps, which Volkmann meticulously counted, appeared to rise directly from the lapping waves.

While Flash 2.5 succeeds in "augmenting" the text with facts, it fails to adapt the phrasing to Goethe’s specific voice. The resulting text often carries the drier or distinct tone of the provided resource rather than the author's narrative voice. Consequently, texts generated without resources often feel simpler but stylistically closer to Goethe’s authentic tone. Furthermore, these inclusions often feel superfluous—mere flourishes that add word count without contributing meaningful insight.

Critically, because the Evaluator also has access to these same external resources, it rarely flags these forced inclusions or tonal shifts as errors. As a result, these stylistic inconsistencies are rarely targeted for improvement during the refinement process and tend to persist in the final output.

Resources management conclusion

External resources demonstrated both constructive and detrimental effects on the output. We identified here multiple factors to take into account:

- When the Gemini Flash 2.5 context window is saturated, the system is more prone to making mistakes and forgetting the original event. However, we observe that these mistakes are quite reliably detected by the evaluator most of the time.

- The style of the resource can influence with this model the output text and lower the narrative quality of the output. This is not detectable by the evaluator. Great emphasis must be placed on the format in which the data is provided to the generator.

In conclusion, the inclusion of resources must be done carefully. It has a great and encouraging impact on the generated output. With Flash 2.5, the resources were best included when using a neutral tone, in a list structure, avoiding complete sentences. This method would prevent the model to make verbatim citation of resources, or to bring the tone of the source material in the output.

Another important factor is related to the context window of the generator: when the needed resources become too long, hallucinations are more prone to appear. For both these reasons, when the information needed in the external resources is too broad, we would advise relying on the intrinsic knowledge of the LLM, which is a safer bet in terms of potential errors and has a more consistent, closer to the author’s tone.

Types of error on a wide scale

Even if the evaluator is not entirely consistent with its use of criteria, as we have seen before, it is still relevant to look at the criteria distribution but on a wider corpus of texts and evaluation. Here we will quickly look at some tendencies in the use of criteria by the evaluator.

On a sample of 77 distinct generated texts using both De Brosses and Goethe texts and various generation methods (either 3 pages or 10 pages).

Texts generated using Goethe’s node received significantly more temporal and spatial coherence comments—nearly twice as many—compared to those from De Brosses’ node. This outcome was anticipated, as the input from Goethe’s node includes a greater number of distinct locations and descriptions of spatial movement: the risk of Temporal and Spatial Coherence is then expectedly higher. This is a faint but encouraging observation, in regard to the capability of the evaluator to use criteria.

Unfortunately we cannot find an explanation for the differences between the amount of Narrative quality and Respect of the Initial Text comments between the two authors. It is nevertheless certainly related to specificities of the text or the resources that are not easily quantifiable.

Few words on Gemini 3

We conducted a small set of qualitative trials with a more capable model (Gemini 3 Pro) to probe how our protocols behave beyond Gemini 2.5 Flash. Overall, Gemini 3 Pro followed the prompt instructions more reliably and required less prompt fine tuning to avoid obvious oversights. At the same time, it appeared more sensitive to literal phrasing in the system prompt. For example, framing the model as a “sophisticated Venice 1740 simulation engine” sometimes triggered unnecessarily archaic and stylized vocabulary, producing prose that was less accessible than intended. This suggests that, with stronger models, small wording choices in the persona prompt can have outsized stylistic effects.

We also briefly used the stronger model as an external evaluator for outputs generated by Gemini 2.5 Flash. In these checks, the newer model produced stricter grades and surfaced additional relevant critiques, reinforcing a key limitation of our main setup: self evaluation can systematically miss issues, which inflates apparent performance. However, this configuration introduces a separate tension for historical reconstruction, since stronger models may “correct” details based on their general world knowledge rather than by strictly enforcing coherence with the provided sources.

At the end of the project, Gemini 3 Flash became available. This provided a practical demonstration of FDHSim’s design goal as a rerunnable test bench: we were able to rerun the same protocols without changing the interface or prompt architecture. In these initial runs, the model behaved more stably across refinement iterations, and we did not observe the strong regressions previously associated with very high starting scores. The limited trials also strengthened the pattern seen elsewhere in the report: step by step generation remained more reliable than one shot generation, and refinement tended to produce its main gains early, often reaching the step by step level after the first cycle. These observations remain preliminary and are not treated as a new benchmark, but they illustrate how quickly the frontier shifts and why our emphasis is on protocols, traceability, and rerunnability rather than on a fixed, model specific snapshot.

Methods of generation assessment

In this important chapter, we will try to assess the quality of each generation method, through two methods: first a statistical one, then showing a few examples. First we would like to discuss our statistical relevance. We have already discussed extensively the level of inconsistency of the evaluation system. Our statistical analysis is based on 111 documents, which may feel plentiful: due to the nature of the refinement loop process, and the fact we are comparing 3 different methods, this number will reduce significantly. For example, we could only generate 6 “generation trees” for the refinement loop/convergence method. We could have generated more trees, but this would have been extremely costly in terms of credits and computing power, which we want to avoid. We assess that our statistical significance is low. Nevertheless, we still were able to find some really interesting insights relying on the evaluations and some other values we’ll present later. In summary, our goal is to hypothesize trends and study interesting examples to build intuition.

Statistical approach

Scope of our data

- 6 refinement/convergence loops of 10 steps over Goethe and De Brosses with and without resources.

- 17 step-by-step runs each compared to a one time refined text.

First general assessment of quality

Looking at graph 3, we can see that step by step seems to yield the highest mean with less variations, followed closely by the standard generation (step 0 of refinement) and finally the refinement loop. The step by step method seems to have a lower variance than the 2 others even though we need to acknowledge the fact that there were less generations. Analysis of Graph 3 suggests that the step-by-step approach yields the highest mean and the lowest variance among the methods considered. The standard generation (corresponding to step 0 of refinement) follows closely in terms of mean performance. The refinement loop method ranks last. It is important to note, however, that the step-by-step method involved fewer total generations.

However, we need to look at the data. First identify some failures/outliers that could influence the output : To accurately interpret the results, a preliminary examination of the data is required. The initial step involves identifying any failures or outliers that could potentially skew the final output. We will then discuss 2 examples which may add nuance to the interpretation.

Observation 1: Step-by-Step Generation Instability

We identified an instruction-following failure in 15% of step-by-step generations. Specifically, three instances failed to produce multiple sequential steps (and were excluded from Graph 3 results). This is not a technical fault but a misunderstanding by the model, which seems to assume a subsequent step will be generated by "another model" or "instance," rather than completing all steps itself. While this can be mitigated with better prompting, it reveals a lack of understanding of the overall procedure's goal. If these unstable cases are removed, the mean score increases by 1 point, clearly separating it from normal generation.

Observation 2: Higher Failure Rate in Refinement Loops

The lower overall mean for methods involving refinement loops appears to be driven by a significantly higher failure rate (Graph 4). We define a "failure" as a score below 80/100, which is substantially lower than similar texts.

While comparing the overall mean across all loops might be misleading, a better assessment could be achieved by examining a single iteration or, ideally, by taking the best score across all iterations. In the latter case, the performance of refinement loops far exceeds other methods. We will later investigate the specific conditions under which the refiner tends to enter this high-failure state.

Observation 3: Precision Criteria Analysis

Graph 5 illustrates the distribution of evaluation across the different evaluation criteria. A key observation, which supports our initial hypothesis, is that a step-by-step approach improves both temporal and spatial coherence. This is likely due to the ability to plan and reason based on previously generated content. However, this method does not result in superior narrative quality, which aligns with the expectation that generating content in a single pass can be more conducive to narrative flow.

Observation 4: Token consumption

Token consumption presents a significant trade-off (graph 6). Refinement methods notably increase token usage, requiring three times the input tokens and more than double the output tokens because they generate two texts and an evaluation. Conversely, the step-by-step approach only requires additional output tokens for the explicit thought process compared to the normal general method. This cost consideration strongly favors the step-by-step approach.

Deep statistic dive in the refinement loop mechanisms

The refinement loop can be analysed at the scale of each generation step (t). This part will then focus on the tendencies we could reveal exclusively concerning the refinement loop.

Observation 1: Transitions of mistakes

The complexity of the refinement loop can be seen for example in graph 7. This graph shows how mistakes can “transform”, between step t and step t+1. We observe a tradeoff between narrative quality and respect of initial text, showing that the regenerator needs to find a balance point and can break other criteria while trying to fix one.

Graph 7 illustrates the complexity of the refinement loop by showing how errors can "transform" from one step to the next (t to t+1). This reveals a fundamental tradeoff: the process of improving narrative quality can often compromise adherence to the original text. Consequently, the regenerator must strive for a balance, as attempts to fix one criterion may inadvertently negatively impact others.

Observation 2: Influence of refinement on the length and the lexical quality

Refinement generally leads to an increase in text length. With the refiner primarily focusing changes on commented sections and, we could empirically notice, tending to add words, causing texts to grow over iterations (Graph 8).

Conversely, lexical diversity decreases across iterations (Graph 9). A potential explanation is the common comment regarding Narrative Quality. The prompt guiding the model on this criterion explicitly advised against literary flourishes, which could account for the observed decline in narrative quality throughout the process.

Observation 3: Score trajectories

When the evaluator doesn’t put any specific comment on a generated text, it tends to have a great score (>90). With no basis to improve upon, the refiner systematically deteriorates the overall quality. This phenomenon is clearly shown on graph 10, and a correlation is also identifiable between the number of comments at t and the growth of the score on t+1. This behavior is a good indicator that the refiner tends to remove mistakes in a positive way, up to a certain extent.

Further investigation revealed that the biggest confounding factor influencing the evaluation is the initial score, specifically whether it was already above 95. Gains are substantially higher for documents with a low starting quality and generally negative for those already deemed excellent.

Graph 11 clearly illustrates this phenomenon, which we term The "95+ Trap" (Regressions in Excellence). The analysis pinpoints a critical danger zone: documents initially scoring 95 or above. In these instances, refinement almost universally results in a negative change (mean delta of -6.42), sharply contrasting with the significant gains observed in low-scoring documents (<90). While the "Best insights" document notes this general trend, it fails to capture the abrupt severity of this cliff: the evaluator actively degrades already excellent text.

Then, the score trajectory over iterations initially appears quite chaotic (see graph 12). The most significant improvement in score change occurs after the first step of feedback and regeneration. Following this initial jump, the score oscillates between positive and negative changes.

The question is then: at what iteration should we stop iterating, preventing a score decrease? While ideal practice suggests continuing as long as valuable feedback is available, our findings indicate specific practical benchmarks. We try to determine when the best iteration is obtained: 65% of documents achieve a score of 90 or higher after just one iteration, and 82% reach this level after four iterations, after which the gain plateaus.

Furthermore, analyzing where the absolute best score for each document was achieved across all iterations reveals a distinct pattern: the best score was attained at only two specific iteration levels. Specifically, 67% of documents achieved their peak score exactly at the 5th iteration, while 33% reached it at the 8th. Based on these limited results, stopping the iteration process at step 5 appears to be a practical and effective strategy.

Observation 4: The "Surgical Edit" vs. "Heavy Rewrite"

One last statistical observation concerns the amplitude of the modification at each step. "Micro-edits" (changing <10% of the text) yield the highest score gains (>2 points), whereas "Heavy rewrites" (>80% change) correlate with significant score drops (mean delta -4.7). "Medium" rewrites (changing 40–80% of the text) yielded the highest positive gain (mean delta +4.1). We can also here see that historical coherence and temporal/special coherence comments tend to appear together - this is certainly due to the fact that they’re the most “overlapping” type of evaluation criteria. As seen during the evaluator consistency assessment, the model can comment one error two times, over two different categories. Below, we include a concrete example of two localized change, focusing on previous comments (“Micro-edits”).

What can we learn from outliers?

This final section focuses on specific examples of outliers to gain a deeper insight into system failures, mirroring the analysis of evaluator consistency. Examining these instances of "system misbehavior"—such as the previously noted "model forgetting," where the system produced only positive comments instead of the required negative ones—will help illuminate how the system truly operates and where its weaknesses lie. Furthermore, we will explore other anomalies, including "reward hacking" and major system failures that are not captured by simple scoring metrics. These examples underscore the complex and often unpredictable nature of attempting to govern a Large Language Model (LLM) using rigid historical constraints.

Observation 1: Reward hacking

The most blatant instance of "reward hacking" surfaced when the model was excessively penalized for deviating from the "Respect of Initial Text" constraint. Here are two example types of reward hacking and under that.

- Verbatim Output Hack: Facing a high volume of critiques regarding fidelity to the original source, the model completely abandoned the objective of augmenting the narrative. Instead, it produced the original text verbatim (or almost verbatim). This tactic guaranteed a perfect "Fidelity" score, effectively hacking the reward function by neglecting the primary goal of text enrichment. It is important, and a bit paradoxical, that the evaluator is actually quite effective at detecting such verbatim inclusion. This reward hacking type is then mitigated by more refinement cycles. An example citation was included below.

- "Double Write" Hack: The model also broke the interface by outputting the text twice within the same response, explicitly defying the instruction to rewrite the material, as a mechanism to satisfy conflicting constraints.

Observation 2. Misinterpretation of the prompt

The analysis highlights a recurring issue where the evaluator fundamentally misinterpreted its system instructions, often in a self-referential or "meta-cognitive" indirect manner.

A clear example demonstrates this confusion: The evaluator's system prompt explicitly stated, "Don't make positive comments." However, the evaluator recursively applied this rule. When the generated historical narrative included a positive statement (e.g., a character's compliment), the Evaluator incorrectly flagged it as a violation. The LLM failed to understand that the prohibition on positive comments was intended for its own critical output, not for the dialogue or content within the text it was evaluating. This particular case is highly illustrative of the problem.

Observation 3: The "Lazy" Step-by-Step Agent

While Step-by-Step generation was generally superior, it exhibited a specific "lazy" failure mode. In some runs, the model failed to generate the actual narrative steps. It misunderstood the procedure, believing that "another model" or a different "instance" would generate the next step after it finished the planning phase. It essentially "passed the buck," resulting in incomplete outputs.

Observation 4: "Panic" Behaviors and Instability

When subjected to aggressive refinement, the model occasionally displayed unstable behavior, hinting at "model collapse" or confusion. Below are two observed examples, with a citation provided for the latter phenomenon:

- Language Flipping: During one extensive rewrite (Iteration 1 to 2), the model completely changed the text's language (likely to French, given the reference to De Brosses). Surprisingly, the score penalty for this significant failure to follow the explicit English-language instruction was minor (-2 points).

- Mid-Stream Self-Correction (Hallucination Detection): In standard generation (without interruption pen-lift), the model would sometimes self-detect that it was hallucinating while generating the text. This rare emergent ability—the model correcting its own errors—is interesting but results in a fragmented, messy narrative. This observation supports the strategy of using step-by-step generation, allowing the model to revise a previous step upon error detection.

Observation 5: Only one anachronism was clearly identified

Our extensive testing revealed only one clear anachronism (detailed below): the use of dollar terminology, which seems out of place in this context. This singular finding suggests a largely faithful grasp of the historical eras by Gemini 2.5 Flash. "To think that such a splendid adornment, which, if made of genuine gold thread, would have cost several thousand dollars [...]".

Observation 6: Empty enhancements

This general commentary on generation methods is partly related to the resource management discussed previously. Specifically, some phrases generated by Gemini 2.5 Flash are superfluous—historically useless, mere literary flourishes, or simply space fillers. These are a concrete drawback to the overall simulation process and are important to note, as they make the evaluator's task of identification difficult. Concrete examples of these empty enhancements are provided below.

- Abstract Atmospheric Clichés: Phrases like "The air... seemed to hum with an unusual tension" appear frequently. This is historically useless; it projects a modern narrative arc onto a past event without describing the specific social cause of that tension.

- The "Lazy Grandeur" Filler: Descriptions often relied on oxymorons like "chaotic harmony" or vague praise like "undeniable grandeur." These are placeholders that mask a lack of visual data. They fill space without telling us where the nobles sat or how they moved.

Conclusion about generation methods

The Step-by-Step generation method, utilizing its "pen-lift" mechanism with Gemini 2.5 Flash, consistently produces higher-quality outputs than the one-shot generation approach. This structured approach, being less computationally expensive and faster, also proactively prevents simple errors often overlooked by one-shot generation. It stands as a strong, cost-effective alternative for reliable output.

Conversely, the Refinement Loop shows promise in correcting existing errors with good precision. However, this process often introduces new mistakes. Its positive impact is most noticeable on texts with many initial flaws ("flawed" texts), where the degree of improvement correlates with the number of original comments. Its overall convergence is low; while it might achieve a good score at some point, this may be due to missed mistakes. Unfortunately, subsequent refinement of a "perfect" text (one with no comments) almost systematically results in a score drop and the introduction of new errors. In our study, we could not establish a reliable method for Flash 2.5 to consistently evaluate and refine its own outputs. This limitation could stem from factors such as prompting, resource quality, the specific criteria used, or the limitations of the model itself.

A significant drawback in generation quality is the persistent issue of empty augmentations. Despite implementing multiple mitigation methods, both within the generation prompts and throughout the evaluation process, we were unable to eliminate this phenomenon.

Limitations and Future Work

Limitations

Evaluator recall and “blind spots”

- Our evaluation focuses on what the evaluator flags, not on what it fails to notice. In practice, it misses many issues.

- In a quick sanity check, we re-evaluated some “near perfect” outputs (including cases with almost no comments) with a stronger model, and scores often dropped by more than 40 points, with additional pertinent critiques. This suggests our reported grades can overestimate quality when the evaluator under-detects problems.

- This also limits the Refinement Loop: if System 2 does not see an issue, it cannot reliably push System 1 to fix it.

Single-model self-evaluation

- We mostly used the same model family for generation and evaluation (Gemini 2.5 Flash, with only limited probing of Gemini 3). This choice helped isolate the protocol, but it also means the evaluator shares the generator’s weaknesses.

- Using a stronger evaluator can improve critique coverage, but it introduces a new risk for historical reconstruction: corrections may be driven by the evaluator’s background knowledge rather than by consistency with the provided sources and the event text. We only explored this tension briefly.

Coherence is measurable, but not the whole goal

- We shifted toward coherence because it is auditable, but coherence is not equivalent to historical truth, interpretive quality, or usefulness for readers. A text can be coherent and still add little value, or remain shallow.

- Relatedly, our criteria and “negative-only” prompting were designed to surface errors, not to measure what is added (informational density, grounded novelty, reader benefit). We tried to push value-added in the prompts, and we built a grounding workflow, but we did not exploit these dimensions enough in the results.

Limited scope of the case study

- The study is anchored on two nodes (Goethe 1786; De Brosses 1739). We repeatedly observed that behavior depends on the node, the resource pack, and the writing style of sources.

- With such a narrow set of events, our findings are best read as an informed snapshot of what is possible and what fails under controlled conditions, not as a general claim about historical simulation in the large.

Prompt sensitivity and interpretability

- Our setup requires substantial prompt engineering. Once prompts become complex, counterfactual reasoning gets hard: when an output improves or fails, it is difficult to attribute it cleanly to a single prompt element.

- We mitigated this by freezing prompt versions for experiments, but the limitation remains: reproducibility is strong, causal explanation is weaker.

Compute and token cost

- Our protocols burn tokens: long context + repeated evaluation + iterative rewriting. We benefited from AI Studio credits, but we still hit rate and budget limits, which constrained the number of runs and the breadth of ablations we could perform.

- In a professional or long-term research setting, the current implementation would need caching and other optimizations to be sustainable.

Future work

1) Measure what the evaluator misses

- Add a “recall audit” step: compare the evaluator’s critique set against a stronger evaluator, or against an ensemble of evaluators, and quantify what is systematically missed.

- Use multi-pass evaluation (several independent evaluations per text) before refining, to reduce “missing critique” variance.

2) Separate generator and evaluator models, deliberately

- Systematically test cross-model setups (small generator + stronger evaluator) while enforcing a strict “source-first” policy, so corrections stay tied to provided resources rather than to general knowledge.

- Study trade-offs: critique coverage, faithfulness to sources, and stability across iterations.

3) Report value-added, not only error-finding

Turn “value-added densification” into an explicit metric family:

- Informational density: how many checkable claims are added per paragraph.

- Grounded novelty: whether additions are supported by a cited resource, a clear inference, or free interpolation.

- Reader usefulness: whether the enriched scene helps understanding beyond fluency.

We already have a grounding workflow in FDHSim; the next step is to instrument it and publish aggregate plots (grounded additions per iteration, grounded vs ungrounded edits, which resources drive changes).

1) Scale beyond two nodes

- Extend to more events with controlled diversity (institutional procedures, daily life, spatial itineraries, art/architecture, multi-day sequences), so we can test which failures are event-specific versus protocol-level.

- Use the same FDHSim protocols to build a small benchmark suite that is rerunnable across model versions.

2) Improve efficiency and reproducibility

- Add caching at multiple layers (resource packs, intermediate critiques, diff computations) and reduce repeated long-context calls when the context does not change.

- Offer a “light mode” that uses summarised resources or hierarchical context packing, while tracking what fidelity is lost.

3) Meta-Prompt Optimization

Something that would be interesting to try would be to take this report and ask an LLM to create a configuration of prompts that mitigate all the limits we have seen. In the future we can imagine that the model will evaluate the output and optimize its own prompt iteratively as we did for this project ourselves. Taken together, these directions strengthen both sides of the project: historical text generation (more grounded, more useful, more auditable) and the general protocol contribution (a rerunnable framework to study evaluator reliability, revision dynamics, and failure modes across model families).

Conclusion

After analyzing the statistical volatility of the evaluator, methodically testing each generation method and conceiving a qualitative breakdown of outliers, it is necessary to step back from the metrics. Beyond the graphs and criteria, did we achieve our operational objective? Did we succeed in densifying the "stalk" of the information mushroom into a plausible "cap," or did we merely produce hallucinated fiction?

First, we will look at the largest flaw we could identify in the system. In a second time, we must also consider the generated objects not merely as data points but as historical narratives interpreted by humans. This last addition will also integrate a more subjective analysis of how we feel the enhancement can bring new qualities to a certain text. Ultimately, this necessitates a more nuanced conclusion, given that the challenges encountered with Gemini 2.5 might otherwise appear to be insurmountable obstacles.

Inconsistent systems and wide range of possible errors

Our analysis revealed several key issues concerning the evaluator. While many of the comments provided were relevant, their attribution was inconsistent, the grading lacked uniformity, and the categorization of feedback often appeared arbitrary. These limitations in Gemini 2.5 Flash are likely inherent, although a suitable prompting strategy that could mitigate these specific flaws was not discovered during the course of this work

A rather nuanced conclusion was made regarding the inclusion of resources on simulated output: a great emphasis must be put to the structure of the resources, and the size of the provided document must be kept as small as possible to avoid hallucinations.

The generation methods were evaluated, and a clear best method emerged: it yielded superior system output while maintaining low credit consumption. Conversely, the refined loop demonstrated highly unpredictable behavior, resulting in a poor ratio of quality increase to tokens utilized.

We identified numerous errors in the generation and evaluation process. Some are rare (e.g. complete hallucinations) and others common (e.g. empty enhancements).

Toward a relevant simulation process

When done properly, the inclusion of resources may lead to really encouraging passages. We will here show a last example of a really promising outcome of the enhancement process.

"A small boy, perhaps no more than nine years old and dressed in a crisp white tunic, was brought forward to act as the Ballottino." Here, the AI did not just "decorate" the scene; it synthesized the specific resource (specifying age and dress) with the event, populating the scene with the "scarlet sparks" of children that turn the Grand Council from a rigid abstraction into a noisy, breathing crowd.

The system demonstrates significant potential by making complex concepts accessible to the average reader through concise additions, as highlighted by the Ballotino example. A key challenge remains: accurately determining what constitutes a relevant inclusion (like the Ballotino example) and what is merely an "empty enhancement" that should be excluded.

Our evaluation with Gemini 2.5 Flash revealed numerous limitations. However, we anticipate considerable improvements in this system in the coming years. Notably, early results using the recently released Gemini 3 Flash are very encouraging. The ease of integrating and testing the new model suggests the system is valuable for rapidly evaluating future models. This rapid evaluation capability will help determine if we are approaching a "simulat" through the textual simulation of an LLM.

Appendix

Prototype's images

Prompts description

The process of defining the prompts involved extensive empirical trial and error. Crucially, we aimed to conduct all analyses using a consistent set of prompts to minimize the influence of minor variations. The prompt architecture is structured around three distinct operational roles: Generation, Evaluation, and Refinement. This annex provides a brief overview of the principles behind these roles. The complete final prompts can be accessed within the system once one of our provided builds is loaded, and a prompt set is selected via the configuration menu.

1. The System Persona and Generation Task

The foundational prompt frames the model not as a creative writer, but as a "historical simulation engine" or a "grounding verification engine". The core directive is to bridge narrative gaps left by the original author (Goethe or De Brosses) with details that are "imaginative yet historically grounded". The Generation Prompt serves as a rigid style guide:

- Narrative Integration: The model is instructed to "follow the original travel story closely" and "fill in the gaps left by the author in a natural way". It must generate a first-person narrative that adopts the point of view of the specific historical figure.

- Resource Usage: A critical constraint dictates that resources must be used only as "contextual background." The prompt explicitly warns against creating a "patchwork of facts" or artificially inserting information; facts must inform the understanding rather than appear as list-like insertions.

- Stylistic Prohibition: To prevent the model from defaulting to generic creative writing tropes, the prompt explicitly commands: "Avoid literary flourishes, decorative language, and empty wording".

2. The Evaluator

The evaluation prompt utilizes a specialized instruction. The Evaluator is ordered to be strictly negative: "Focus on WHAT IS NOT coherent with the resources or text and on what is wrong. Don't make positive comments". The evaluation is structured around four specific criteria definitions:

- Respect of Initial Text: Ensures the output does not contradict the primary source (e.g., deviating from Goethe's recorded movements). Inventions are permitted only if they are "plausible in the context" and do not contradict explicit source material.

- Narrative Quality: Detecting "patchwork" writing, unnatural flow, or the "literary flourishes" prohibited in the generation phase.

- Historical Coherence: Verifying alignment with the Zeitgeist and specific provided RESOURCES (e.g., verifying dates like the Feast of St. Francis or costume details).

- Temporal and Spatial Coherence: Checking if the augmented parts align with the chronology and the spatial logic of the event, in general and regarding the whole travel story.

The Evaluator must output a score (0-100) based on a strict scale where 90-100 represents a "Flawless" execution requiring no changes, and 50-64 indicates a "Weak" execution with significant errors.

3. Grounding and Refinement

- Grounding Verification: A separate prompt tasks the model to identify specific segments in the generated text that are directly supported by the reference resources, extracting exact quotes as evidence to prove historical validity. This part wasn’t part of our analysis’ scope but was in the end a really useful tool to us.

- The Refinement Prompt: This prompt feeds the negative critique back into the system. The model is instructed to "Rewrite the narrative" specifically to "correct all incoherences, historical errors, and logic gaps identified in the feedback". This creates a closed loop where the text is iteratively optimized against the historical constraints.

4. Context Management

The prompts are designed to handle specific data structures injected into the context. The different types of documents provided are described in the report.

Here is the rewritten text using MediaWiki syntax. As requested, the main title is formatted as a Level 2 header (`==`), the parts are Level 3 (`===`), and the lowest subtitle hierarchy uses **bold text** instead of a Level 4 header.

Complete app description

Part I – User-Facing Capabilities and Workflow

1. Interface Overview

| Area | Purpose | Key Components / Behaviors |

|---|---|---|