Opera Regeolocation in Venice (1660-1760)

This project is led by Christophe Bitar and Eliott Bell, master students at the EPFL, as part of the course DH-405 Foundations of Digital Humanities, taught by Prof. Kaplan, Collège des Humanités, EPFL.

Introduction

GitHub repository (data extraction)

Motivation

"Un affolement inconcevable" for music in Venise, according to Charles de Brosses (Lettres familières d’Italie, 1739-1740)[1].

A city filled with music, Venice had a dozen opera houses between the 17th and 18th centuries. It was in Venice that the first public opera house, Il Teatro San Cassiano, opened in 1737. This marked the beginning of several generations of artists (composers, librettists, singers, and instrumentalists) who devoted themselves to the art of opera on stage. It was a dynamic environment that brought together various professions, competition, and audience affinities. Many people passed through Venice and left their mark on the vibrant world of opera.

Our journey for this project is summarized in the following mind map.

Research questions

Initially, we wanted to accurately trace the life of Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) by parsing a biography. However, due to a lack of sufficiently precise information in terms of places and dates, we ultimately decided to transform a reference book on opera in Venice into an exploration interface, a starting point for visualizing life stories by integrating a search for named entities identified by NER.

The reference book is Eleanor Selfridge-Field's, which lists all the operas performed in Venice between 1660 and 1760 (to our knowledge). Based on the book, we therefore propose to put the operas performed in Venice on a map, offering users a tool for exploring, comparing, discovering, and following an institution or an artist's productions over time. Thus, our work consists of transforming this work into a database and building an interface that allows users to explore this data in order to better understand musical life in Venice in the opera market. This tool is a gateway to reconstructing artists' careers.

Main Reference : Selfridge-Field E. (2007). A New Chronology of Venetian Opera and Related Genres, 1660-1760. Stanford, Stanford University Press.

State of the art and litterature

We looked to see if other projects existed that had already created a database of operas in Venice. It turns out that the CORAGO project, led by the University of Bologna, offers a database of all the operas performed in Italy during the Baroque period. However, this database does not include any visualizations or offer a CSV file for playing with the data. Nor are there any references to specific named entities involved in the opera productions.

Literature on music in Venice, and more specifically opera and its theaters, is available at the bottom of the page.

Project plan

Here is the plan for our project. The core idea is to represent on an interface the information about operas given in Venise between 1660 and 1760, according to the book of Eleanor Selfridge-Field (Standford 2007). We collect data about composers, writers, dates, opera houses.

After the midterm presentation of the project, we divide the work in two. Christophe works on the interface implementation while Eliott works on the last elements of the database.

The planning is made by modules : if we manage to achieve one part, we can continue and enrich the data. This model guarantees to achieve the Minimal Viable Project, consisting in showing the opera through time and space. The NER extraction, possibly more difficult, would arise only if we have time. We ensure also to have sufficient time to debug the interface and analyze the results.

| Week | Eliott Bell | Christophe Bitar |

|---|---|---|

| Week 7 | Scan & OCR | Litterature finding |

| Week 8 | Pattern matching | State of the art |

| Week 9 | Midterm presentation | |

| Week 10 | Matching and cleaning data | Working on the interface |

| Week 11 | NER of entities | Working on the interface |

| Week 12 | Implement full database - Cleaning data | |

| Week 13 | Debugging, feedback, analysis | |

| Week 14 | Final report | |

Methodology

From a book to a database

OCR

The first concrete step of the project was to extract as much relevant information from A History of Venetian Opera and Related Genres as possible in order to create an extensive historical dataset. To that effect, after a digitised copy of the book was found, an optical character recognition (OCR) scan was performed on the PDF file to retrieve the text content. This was done using the python-tesseract library.

Once this was done, some superficial data cleanup was performed in order to remove any non-standard characters that wouldn't be handled correctly by the next few functions.

Pattern matching

Two different methods were used to extract the desired data. For the basic, systematic information about each opera (i.e. its title, writer(s), librettist(s), venue and sorting date), the decision was taken to use pattern matching, as said data was well-structured and lacked context. The procedure was to identify the pattern used by the author of the book, write the regular expression corresponding to that pattern, then match the entries and patterns to retrieve the desired data in an automated procedure.

To make data extraction more consistent, a few adjustments had to be made to the regexes in order to make them more flexible, as certain entries contained some inconsistencies and additional information. After the adjustments, the few errors that remained were corrected by hand in the final dataset in order to keep regexes reasonably short.

Once the dataset was consistent, it was exported into a JSON file. In addition to the data, a unique ID was added to each opera entry in order to easily cross-reference the database with the following elements.

NER

In addition to the systematic data on each opera, most entries in the book feature a text paragraph disclosing information about the context the opera was released in. To retrieve some of that information, a named entity recognition (NER) scan was done with the Python spaCy library. For each opera production, a list of named entities, including locations and people, was extracted. The decision was then taken to select the 100 most frequently mentioned entities, along with the entries and specific sentences in which they appear. Some entities were discarded from the set for different reasons, such as lack of interesting information (the most frequent entity was “Venice”), being too vague (e.g. surnames that could refer to multiple people), being inaccurate, etc.

The resulting JSON file features the same UID system as the original database to link them in a consistent manner. Alongside the named entities, the spaCy library allows for extraction of the sentence an entity appears in, which is stored as the ent.sent.text object. In order to provide more information on the context in which these entities appear, these sentences were included in the dataset as well.

Enriching the data

Finding coordinates

Determining the precise coordinates of Venetian theaters presents significant challenges. Some no longer exist, others have undergone transformations and name changes (e.g., Teatro Malibran, formerly Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo, founded in 1678), while others exist today but were not present during the period in question (e.g., La Fenice, 1792).

The initial phase involved querying the Wikidata database for opera houses in Venice.

Certain venues were missing, either due to their absence from the database or because they were located outside the city of Venice proper (e.g., Villa Contarini, approx. 50 km west of the lagoon). To supplement the missing coordinates, recourse was made to the following auxiliary sources (maps, encyclopedias, and narratives):

- Jérôme de La Lande, Voyage d'un françois en Italie, fait dans les années 1765 et 1766, Atlas / , contenant l'histoire & les anecdotes les plus singulières de l'Italie, & sa description, les moeurs, les usages, Venice, chez Desaint, 1769. BEIC

- Giovanni Salvioli, I teatri musicali di Venezia nel secolo XVII (1637-1700), memorie storiche e bibliografiche, Milan, Ricordi, 1878. NUMiSTRAL

- Giuseppe Tassini, Alcuni palazzi: ed antichi edificii di Venezia, Venice, Filippi Editore, 1879. Wikimedia

Interface design

The web interface is built upon an HTML architecture hosted on a GitHub Repository. It features a main index comprising JavaScript sections and renders maps using Leaflet.

The functionalities were primarily developed with the assistance of Google AI Studio, through a process of trial and error, successive corrections, progressive comprehension of the interface, and updates driven by debugging and research requirements.

The interface offers a slider to filter the dataset, and a map where circles represent data corresponding to the search criteria. It includes a heatmap mode and a comparison mode to visualize two distinct search queries in different colors. Users can thus restrict the data to specific composers or librettists, causing the visualization to update dynamically. Furthermore, users can search for named entities (e.g., cities, patrons, artists), observe their temporal and geographical representation, and retrieve specific excerpts from the source text citing the entity, thereby contextualizing the query.

A burger menu, located in the upper-left corner, allows for basemap selection and toggling of dark mode. A historical basemap was not selected because, although the visualization is based on period data, it relies on information as it has been preserved to the present day. Moreover, given the minimal evolution of the Venetian urban fabric (lagoon), the added value would have been negligible compared to the time required to precisely georeference a historical map. Credits and a brief description are also accessible via the menu.

Results

Interface Usability

Comparison mode

In order to allow comparative data analysis, a "Comparison Mode" was implemented into the interface. It enables users to apply two search filters in parallel.

Entity search

Alongside the standard method of filtering operas based on theater, composer or librettist, an option to quickly browse through entities mentioned in the entries was implemented. By selecting a certain entity, the map filters operas that mention it and the sidebar shows a list of said operas as well as the sentence the entity appears in, allowing many opportunities for deeper research. Some of them are discussed in the Historical results section.

Data exportation

When filtering entries by any criteria, users can export the list of all corresponding operas in a CSV file.

On top of that, an option to easily export and download visual data from the map of Venice was added next to the histogram. This allows users to seamlessly take screenshots of the desired data, or even create GIFs showing its evolution through time and space.

Historical results

First overview

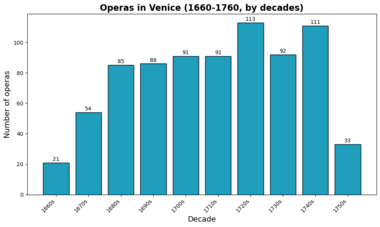

We begin by dividing the period (1660-1760) into decades, which also corresponds to the division used by Eleanor Selfridge-Field. As the data ranges from 1666 to 1752, the extreme decades are less well represented. Otherwise, opera production in Venice was significant throughout the period, reaching its peak in the 1720s after steady growth.

If we look at production by theater, we get the following distribution, which shows the Teatro San Angelo (184) and San Giovanni Grisostomo (164) in first place, followed by those of San Moise and San Cassiano (with about 100 productions each), followed by smaller theaters or those with a shorter lifespan (San Giovanni e Paolo, San Samuele). The remaining theaters (Teatro di Cannaregio, Santa Margharita, SS. Apostoli) accounted for only a handful of performances during the period. It should also be noted that Villa Contarini is located outside Venice.

As for composers and librettists, two figures stand out among the composers: Carlo Francesco Francesco Pollarolo (1653-1723) and Tomaso Albinoni (1671-1751). However, when comparing their respective Wikipedia pages (English version), we see that there is no correlation between the number of operas performed in Venice and the size of their Wikipedia page. The latter factor is considered a measure of contemporary “knowledge” about these figures.

The literature on Francesco Carlo Pollarolo is sparse. In Ellen Rosand's book, Opera in Seventeenth-Century Venice: The Creation of a Genre (Univ. of California, 1990), he is mentioned only once. Assistant organist at St. Mark's Basilica and choirmaster at the Ospedale degli Incurabili, he deserves to be studied more. Olga Termini has devoted her research to this composer.

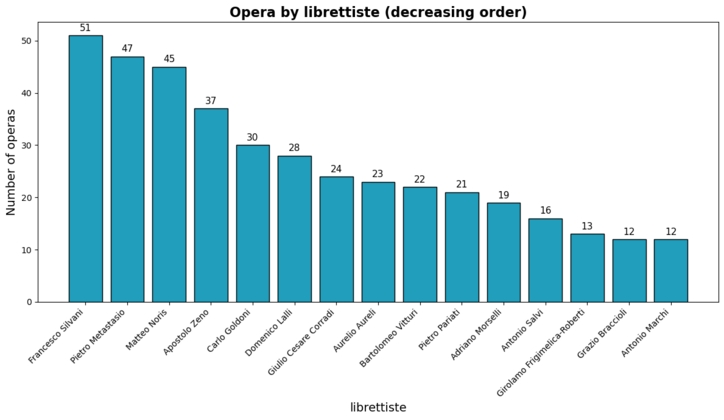

The same observation applies to librettists. While Francesco Silvani (1728-1744), Pietro Metastasio (1698-1782), and Matteo Noris (1640-1714) are the top three, Noris has a very brief page, while Silvani simply has no Wikipedia page at all in English. The authors most frequently referenced in the online encyclopedia are not the most frequently performed and vice-versa.

The artistic ecosystem (1) : Relationships (Theaters, composers & writers)

Let us now consider the relationships between the various entities (theaters, composers, and librettists). First, we observe the relationships between composers and theaters (composers are generally present at the creation of their work, which is not necessarily the case for librettists, who may have died if the text used is older). By dividing the period into three sub-periods: (1) 1660-1690 (2) 1690-1720 (3) 1720-1760, we can see that the loyalty between composer and theater changed during the period.

In the first period (1660-1690), with the exception of Antonio Sartorio, who was loyal to San Salvatore, the other composers were performed in several theaters. There may have been one or more (as in the case of Carlo Pallavicino) main venues.

Between 1690 and 1720, however, a chapel dynamic seems to have emerged. Composers were mainly performed in one theater. It is conceivable that administrative or emotional ties (contracts, proximity, audience loyalty) may have bound the various players within a flourishing market. We can also imagine stronger competition, since the markets seem to be more separate from each other. However, this approach must be qualified, as Pollarolo clearly exceeds the statistics for the previous period. Nevertheless, the dynamic has changed.

Finally, after 1720, theaters had programming that included a greater diversity of composers.

Finally, let's focus on the composers and librettists most frequently performed by decade over the entire period. What were the top 10 per decade? What trends stand out?

The two bump charts group together composers who appear at least once in the top 5 composers over a decade. The top 15 is displayed by decade, with the most played at the top. Among composers, Carlo Francesco Pollarolo leads between 1690 and 1710 (he died in 1723). Each decade sees the emergence of new names: Albinoni (in orange), then Vivaldi (in light green) and finally Galuppi (in dark green). The latter is one of the representatives of the galant style, which emerged around 1720 in Europe and, as we can see, tended to become dominant in the mid-18th century.

On the librettist side, the bump chart reveals a gradual emergence of new names: the curves grow over two decades, before reaching their peak and losing popularity in the following decades. We thus find the following progression of librettists: Aurelio Aureli (blue), Matteo Noris (purple), Francesco Silvani (dark blue), Apostolo Zeno (green), Pietro Metastasio (red), Carlo Goldoni (purple)). The latter is representative of opera buffa, a genre originating in Naples, which was very fashionable in the mid-18th century[2].

Finding the right Chronology (1)

The disparities between eras lead to a new question: was our initial chronological division relevant? Is it possible to find a division that would reinforce the distinction between the dynamics of the relationship between composer and theater?

If we study the composers played by five-year period, we can use cosine similarity to identify the moment(s) when there are the most differences between two eras. If we disregard the last peak, which only represents the absence of data at the end of the period, we can see that there is a peak in 1691.

The artistic ecosystem (2) : Market and Seasonality

Theaters as incubators

We have already discussed the different composers who performed in different theaters. We can now look at the types of composers who performed in each venue. Were they composers who already had a career behind them, or young talents? Can we say that theaters are incubators, springboards for young artists?

If we look at which theaters perform composers who are played in Venice, we see that it is precisely the two theaters with the shortest longevity (San Giovanni e Paolo, San Samuele) that have programmed composers who had not yet been played in the city. The largest theaters (Sant'Angelo and San Giovanni Grisostomo) are 4th and 5th in ranking. It should be noted that the values are relative. The figure on the right clearly shows that, in absolute terms, the large theaters have produced more composers who have never been performed there before. Are these young artists or international guest composers?

We have analyzed the presence of composers in theaters. The same could be said for librettists, even if the previous remark concerning the potential absence of librettists during the creation of works still applies. Nevertheless, we should note the case of Carlo Goldoni, an outstanding librettist in the opera buffa genre, who made his debut at the Teatro San Samuele before performing throughout the city. The nephew of the city prosecutor, he was an intern in the premises adjacent to the theater where he would become director in 1737.

Salaries

The issue of artists' fees is revealing of the ecosystem within the art market. It highlights tensions, hierarchies between different professions, margins for negotiation, and the cost of living. By parsing the entities named in the work, we were able to identify several references to salaries and compare them. We can see how Vivaldi negotiated the price for an opera (1713), how much the castrato Farinelli received for three productions (1729-30), and how the issue of financing travel between different cities seemed crucial for singers. We observe also that some singers can command higher fees (stars), while instrumentalists are paid less than singers for a production.

| Currency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lire | Farinelli, singer (1729-1730) Payment for 3 operas (Mitridate, Idaspe, Artaserse) : "Carlo Broschi (Farinelli), noted for his enormous range and agility, was paid 18,600 lire for his appearances..." | Niccolò Jommelli, composer (1741) : Payment for one opera (out of 6,802 lire total revenue) : "Jommelli's regalo was 2,684 lire, with a later supplement of 12 zecchini. | Nicola Porpora, composer (1742) : "The total proceeds [...] came to 6,802 lire, of which Porpora was paid 2,420 lire." | Francesco Rossi, impresario (1710) : "Fee per night (per performance)" : "Francesco Rossi [...] had agreed in a June contract to pay Pasi 9 lire a night..." |

| Gold pistoles | Domenico Cecchi & Margarita Pio, (1679) singers : for 2 productions (San Salvatore) : Cecchi and Margarita Pio each received 400 gold pistoles..." | Giulia Romana, singer (1679) : for 2 productions (San Salvatore) : "...while Giulia Romana received 250 [gold pistoles]." | ||

| Ducats | Maddalena Musi, singer (1690) : for previous accounts : "She also requested 1,000 ducats from San Salvatore to settle previous accounts." | Antonio Vivaldi, composer (1713) : amount withheld from Heinichen : "Vivaldi withheld the 200 ducats he had promised Heinichen for the two works." | Carlo Fedeli, instrumentalist (1683), Claim for rehearsals and performances (?) : "The San Marco cellist Carlo Fedeli (Saggion) filed a claim [...] for 100 ducats..." | |

| Zecchini | La Marchesini, singer (1725) : Demand for travel : "His effort to take Marchesini to London was thwarted by her demands of 1,500 zecchini..." | Antonio Vivaldi, composer (1737) : (Offer refused) for an opera: Vivaldi twice declined [...] first because he was offered only 90 zecchini, then, when offered 100 zecchini... | ||

| Doppie | Maddalena Musi, singer (1690) : Offer refused : "...Maddalena Musi had rejected an offer of 200 doppie from San Salvatore..." | Vittoria Tomi, singer (1682) : Promised fee : "It appears that the singer Vittoria Tomi was promised 120 doppie..." | Monsieur de Noie, instrumentalist (1706) : Demand for a performance : "...insistence of the oboist Monsieur de Noie on a regalo of 100 doppie..." |

Seasonality of operas

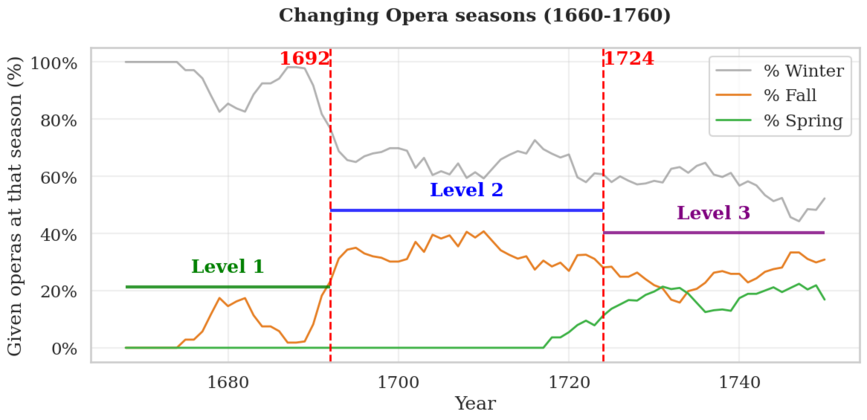

One of the distinctive features of musical life in Venice is the importance of the opera calendar throughout the year. Opera performances follow the rhythm of the seasons and the liturgical calendar. The season usually begins in winter with Carnival, and there are no operas during Lent.

We have observed that no opera from the database was performed in April (as the dates of Lent change from year to year, it is more difficult to verify this condition systematically and accurately). Furthermore, only three operas were performed in the summer, two of which were at Villa Contarini, located outside Venice. The last summer performance was in 1726 at San Samuele, coinciding with the visit of a cardinal.

We will therefore focus solely on the three remaining seasons: winter, spring, and fall. Theaters can thus be classified according to their seasonality. The figure opposite shows that fall and spring are much less represented, while winter accounts for the vast majority of performances. The San Samuele theater seems to only give performances during this season.

If we look chronologically at the distribution of operas during the period and divide it according to the breaks noted above (1690 and 1740), we see that Autumn and Spring only come later. We need to look more closely at the chronology and find where to divide the period in order to identify the turning points.

Finding the right Chronology (2)

An optimization algorithm is then applied to identify the dates on which to apply the time hinges. Three chronological phases are set a priori. For each division—creating periods of at least 10 years—the one that results in the most significant change in terms of distinction between each phase is calculated. The optimization algorithm returns the dates 1692 and 1724 in order to maximize the differences between each section. This brings us back to the turning point of around 1690 previously identified for composers. Further research would be needed to determine whether there are other elements that correspond to this chronological division.

It is clear that the three periods are distinct, with operas emerging in the fall between 1692 and 1724 and a spring season beginning in the 1720s.

Venise and the rest of the world

The world of opera does not stop at Venice. It is a veritable network that spans Europe, with musicians following its branches. It is particularly noteworthy that some operas are performed elsewhere before arriving in Venice, while others are premiered in the lagoon city. Without being able to generalize, we have noticed in studying the different locations identified that Rome generally precedes Venice, while Venice anticipates Naples, Florence, or Bologna. On the other hand, in the 18th century, it seems that the situation was reversed between Venice and other Italian cities. Venice tended to perform works that had already been performed elsewhere. However, there are exceptions to this analysis, and a detailed analysis of the graph would be needed to explore this observation further.

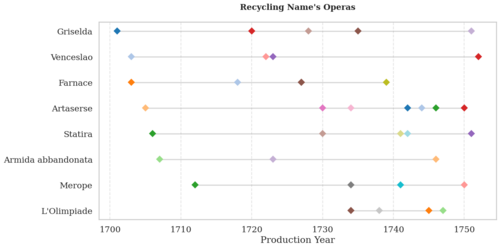

It should also be noted that in the 18th century, several names recur in the titles of operas, as if certain themes were being recycled. It is difficult at this stage to make concrete assumptions about these cases. The table below gives some examples of emblematic figures that are repeated throughout the productions in Venice.

Discussion and limitations

Technical issues and potential improvements

OCR inaccuracies

A frequent issue with the OCR scan occurred due to the language model used: since the pytesseract library uses a very basic English character set for its detection, some characters weren't recognised properly. This is most prominent with the "ò" character, which often became "d" or "e"; thus, for example, the composer Niccolò Jommelli often became Niccold or Niccole. Such errors had to be corrected by hand upon being noticed, though some may remain in the dataset due to lack of a thorough human examination.

Another problem that might have arisen due to OCR errors regards entry separation. The different opera entries were split using an instance of pattern matching: as all entries end with a line that starts with "Listed as", this was used as the separation rule. However, there might be cases where OCR wrongfully detected different characters in this line; were that the case, the following entry would have been entirely omitted from the extraction. This could also be detected and corrected with an entire comparison of the original source against the resulting dataset.

NER limitations

The NER scan presented two main issues. The first one is due to the fact that in its base form, spaCy is unable to detect the layout in a document. This especially becomes an issue when it comes to footnotes, as the entities they mention often end up linked to the wrong entry. This is also in part due to the way entries were split after the OCR scan. A potential fix would be to use a document layout analysis tool to associate footnotes to the right paragraphs before performing NER; for example, this could be done with the spaCyLayout extension for spaCy.

Another issue stemming from the lack of layout recognition is the fact that no distinction is made between entities mentioned in the historical context and the ones appearing in the opera's synopsis. This becomes an issue in some entries in the database, such as Armenia, which is mentioned in 14 operas, but always as part of the plot. This in turn doesn't provide much relevant historical insight.

The second issue with the NER scan revolves around the context sentences extracted alongside the entities: the delimitations often aren't correct, creating a lot of inelegant entries saturated with irrelevant information. For example, the entry for the opera Arianna e Teseo (1750) mentions the city of Vienna; the context sentence that was extracted reads:

Winter (St. Stephen's) With balli SORTING DATE: 1750-12-26 Without dedicatee Pariati's text had been set by Porpora in 1714 for Vienna and was produced in Venice as 1727/11.

The issue might again come from a lack of layout awareness, as everything prior to the relevant sentence is in fact part of different paragraphs.

Interface bugs

Though the interface mostly functions as intended, a few minor bugs remain, the most prominent of which being an issue with the way the map displays Comparison Mode under certain unclear conditions. This could be fixed with more time spent debugging the website.

Data extraction

In A History of Venetian Opera and Related Genres, each entry additionally features the genre of the opera, which wasn't incorporated into the dataset due to a lack of time. The genre of each work could be a valuable piece of information to add, as analysing the evolution of different musical trends can be a crucial tool in order to get a grasp of an era's zeitgeist.

Historical limitations of the method

All results are based on the premise that the data in the reference book is accurate and virtually complete, which we have not questioned.

Even though we took the trouble to proofread the database as thoroughly as possible, it is possible that errors due to OCR remain and distort the results. This problem also arises for the recognition of named entities. There is a “domino effect” where upstream errors affect downstream tasks.

We decided to represent operas over a one-year period in the database because, although the premiere date is always indicated, the end date is not always known. Also, for practical reasons of visualization and data access, we preferred to display each opera in a single year.

The visualization on the interface is highly interactive and engaging, allowing users to explore questions about the data and better understand the dynamics of the subject at scale. However, despite the introduction of the GIF tool, it is difficult to capture findings and further research without returning to the database. On the other hand, converting to a CSV file makes it easy to base the exploration tool on a more precise selection of data and continue the in-depth work.

We would need to cross-reference our findings with other contemporary sources to substantiate our historical results. While this approach does not directly enable us to trace individuals' journeys, it does allow us to gain a better understanding of the context, the issues at stake at the time, and the Zeitgeist within the highly dynamic art market of opera in Venice. Cross-referencing with contemporary sources would allow us to clarify certain details, while this at-scale approach provides an underlying context for the testimonies, which would be more difficult to find in personal sources.

What we learnt

From a technical point of view, we learnt lots of new tools (OCR, NER, Leaflet) and code skills (Python, Javascript, Wiki Markup). We observed the importance of cleaning data and the time needed on processing the data before analyzing. Planning and sharing tasks was important and useful.

From an historical point of view, we saw that visualisation and data analysis cannot tell everything about history and should be combined with other qualitative sources to fuse context and precision. Through the exploration, it opened questions for data analysis and we discovered new (hidden?!) composers from the past. Thus it gives a new perspective on history but it’s not complete. There are now new questions to answer with this new perspective "à vol d'oiseau".

References

Opera in Venice

- Selfridge-Field E. (2007). A New Chronology of Venetian Opera and Related Genres, 1660-1760. Stanford, Stanford University Press. [Book-reference]

Music in Venice

- Baldauf-Berdes JL. (1993). Women Musicians of Venice : Musical Foundations : 1525-1855. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

- Mamy S. (1996). La Musique à Venise et l’imaginaire français des Lumières : d’après les sources vénitiennes conservées à la Bibliothèque nationale de France (XVIe-XVIIIe siècle). Paris, Éditions de la Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- Selfridge-Field E. (1985). Pallade veneta : Writings on Music in Venetian Society, 1650-1750. Venezia, Fondazione Levi.

- Talbot M. (1999). Venetian Music in the Age of Vivaldi. Ashgate, Aldershot.

Theaters in Venice

- Giron-Panel C. (2010). A l’origine des conservatoires : le modèle des Ospedali de Venise (XVIe-XVIIIe siècles), thèse pour le doctorat d’histoire, sous la direction de Monsieur Gilles Bertrand et de Monsieur Giovanni Morelli. Université de Grenoble / Università Ca'Foscari – Venezia. Soutenue le 30 octobre 2010.

- Mamy S. (1994). Les grands castrats napolitains à Venise au XVIIIe siècle. Liège, Mardaga.

- Pincherle M., Marble, MM. (1938). "Vivaldi and the "Ospitali" of Venice". The Musical Quarterly, 24.3, 300-312.

Credits

Course: Foundation of Digital Humanities (DH-405), EPFL

Professor: Frédéric Kaplan

Supervisor: Alexander Rusnak

Place and time-stamp: Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, EPFL, 17th of December 2025

Authors: Christophe Bitar, Eliott Bell

- ↑ Quoted in Giron-Panel C. (2010). A l’origine des conservatoires : le modèle des Ospedali de Venise (XVIe-XVIIIe siècles), Université de Grenoble / Università Ca'Foscari – Venezia, 2010, p. 191.

- ↑ As the bump charts are initially dynamic plotly animations, not all the artists' names are displayed. Readers are kindly referred to the associated Notebook in the GitHub Repository.