Universal Aesthetics (Multimodal Focus)

Introduction

This project investigates the concept of "Universal Aesthetics" within the context of Artificial Intelligence models, specifically Large Language Models (LLMs) and Vision Transformers (ViTs). Our central hypothesis is inspired by : "All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way" [1] for AI representations. We propose that texts and images deemed "aesthetic" or "beautiful" exhibit greater representational convergence across diverse deep learning models than their less aesthetic counterparts.

The project is structured into two main phases. Phase 1: Language Component explores the convergence of seven distinct open-source LLMs on textual data, comparing poems (hypothesized to be more aesthetic) against plain descriptive texts. Key research questions focus on whether models converge better on poems and identifying underlying mechanisms such as semantic similarity and textual rarity (using perplexity). Phase 2: Multimodal Component extends this inquiry to the cross-modal domain, examining the mutual convergence between seven LLMs and seven ViT models on Image-Text and Image-Poem pairs, and analyzing the impact of image aesthetic scores.

This study validates the Platonic Representation Hypothesis on aesthetic data and provides insights into how aesthetic factors influence model alignment and representation space. Our findings suggest that aesthetic attributes, rather than being complex or high-level features, may be fundamental elements mastered relatively early in a model's training process. All datasets, code, and this wiki web page are open-sourced as key deliverables.

Project Plan

The primary goal of this project is to investigate the "Universal Aesthetics" in the context of Artificial Intelligence models. We hypothesize that "All beautiful things are alike; each ugly thing is ugly in its own way" for AI models. This plan is divided into two phases: the Language Component (comparing poems and plain descriptive texts) and the Multimodal Component (comparing image-text and image-poem pairs).

Phase 1: Language Convergence and Aesthetic Factors

This phase focuses on answering the core research questions: Do models converge better on poems than on plain texts? and What is the underlying mechanism? To answer these questions, we need to perform the following exploration:

1. Data Preparation and Annotation: Acquire and clean a large dataset of poems from Kaggle, filtering for English content and removing noise (e.g., copyright notices). Assign aesthetic scores to the poems using the GPT-4o large language model on a 5-point scale. This annotated dataset is open-sourced on Hugging Face.

2. Model Convergence Experiments and Comparative Analysis: Measure the mutual convergence of a diverse set of seven open-source Language Models (LLMs) (ranging from 560M to 8B parameters, including Llama-3, Mistral, Gemma, and BLOOMZ) using the Mutual kNN metric. Compare model convergence on "Poems vs. Plain Texts", "High-Aesthetic-Score Poems vs. Low-Aesthetic-Score Poems", "Structured (Formated) Poems vs. Free Verse (Non-formated) Poems".

4. Bias Reduction and Mechanism Investigation: Address the text length bias by aligning the length distributions of the poem and plain text datasets. Investigate underlying factors like "Semantic Similarity/Topics" (using K-means clustering [2] and word embeddings) and "Rarity" (using Perplexity calculated by GPT-2) to explain convergence patterns. Beyond Narrative Description: Generating Poetry from Images by Multi-Adversarial Training

Phase 2: Multimodal Convergence

This phase explores whether the observed aesthetic principles affect cross-modal alignment, addressing the question: Is cross-modal (language and vision) convergence also impacted by aesthetic factors? To answer the question, we need to perform the following exploration:

1. Image-Poem Data Creation: Utilize an existing Image-Text dataset to generate an enriched Image-Poem-Text dataset of approximately 1,000 entries, using a neural network-based image-to-poem generation pipeline. Assign an aesthetic score to each image.

2. Cross-Modal Convergence Measurement: Measure the mutual convergence between a set of seven LLMs and seven Vision Transformer (ViT) models on "Image-Text" and "Image-Poem" pairs.

3. Aesthetic Impact Analysis: Compare the cross-modal convergence (LLM vs. ViT) on images with different aesthetic scores for both Image-Text and Image-Poem pairs.

Milestones

| Milestone ID | Description | Week |

|---|---|---|

| M1 | Clean raw poem data. Open-source the annotated poem dataset on Hugging Face. |

3.11 - 9.11 |

| M2 | Annotate ~800 poems with aesthetic scores. Compute Mutual kNN for all model pairs on the original Poem and Plain Text datasets. |

10.11 - 16.11 |

| M3 | Analyze convergence based on model capability and parameter size. Conduct comparative experiments on aesthetic score and poetic form subsets. |

17.11 - 23.11 |

| M4 | Perform length-aligned sampling of Plain Text and Poem datasets. Perform representation space alignment sampling on Plain Text. Investigate the roles of Semantic Similarity/Topics and Rarity on convergence. |

24.11 - 30.11 |

| M5 | Generate the Image-Poem-Text dataset and publicly release it. Measure cross-modal convergence for Image-Text and Image-Poem pairs. Analyze the impact of image aesthetic scores on cross-modal convergence. |

1.12 - 7.12 |

| M6 | Compile all experimental results, interpretations, and analysis into the main deliverable: this Wikipedia page. Release all associated code, result files, and output images on the Wiki page and GitHub. |

8.12 - 14.12 |

| M7 | Final check. Prepare the presentation. |

15.12 - 18.12 |

Motivation

"Representations in AI models, particularly deep networks, are converging." This is the conclusion from the paper The Platonic Representation Hypothesis [3], which coincide with the Anna Karenina principle"[1]:

Все счастливые семьи похожи друг на друга, каждая несчастливая семья несчастлива по-своему.

All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

Inspired by this principle, there is another interesting topic closely related to digital humanities: is this principle also applicable to beautiful things? That is to say:

All beautiful things are alike; each ugly thing is ugly in its own way (for AI models).

This hypothesis can lead to a deeper exploration based on the Platonic Representation Hypothesis work, as language models and vision-language models can encode texts and images with different aesthetic levels (operationalization), allowing for quantity analysis. To simplify the question, we categorize the aesthetic degree of the text into poetic text and descriptive, plain text, and we hypothesize that poetic text is more 'aesthetic' (or 'beautiful') than plain text.

Research Questions

Given the core concept of the Anna Karenina principle on aesthetics, we divide this project into two parts: the "language" part on descriptive texts and poems, and the "multimodal" part. and develop research questions as follows:

- Do models converge better on poems than on plain texts?

- If the models do converge better on poems, what is the underlying mechanism that distinguishes poems and plain texts?

- Is cross-modal (language and vision) convergence also impacted by aesthetic factors?

Deliverables

The main deliverable of this project is this Wikipedia page. This page includes the experiments conducted, along with the corresponding interpretations and analysis.

The poems dataset we annotated has been open-sourced on Hugging Face, with the following branches described below:

- main is the primary dataset we used.

- The large branch contains more annotated data, but due to computational limitations, we did not perform model embedding on it; it can be used to analyze other features of the poems, such as lexical, format, aesthetic score, etc.

- aligned_5 contains the sampling results where the length distribution matches the minhuh/prh dataset, including repeated sampling.

- aligned_s contains the sampling results where the length distribution matches the minhuh/prh dataset, but does not include repeated sampling, resulting in a smaller data volume.

We provide the GitHub repository, which contains all the code for the aforementioned experiments (including the experiments and plotting), as well as the output images and result files (text features, clustering results, text-form alignment results, and semantic embedding results).

Another Image-Poem-Text dataset with nearly 1000 entries is also made public. The dataset is developed from a randomly sampled subset of image-description-dataset. We use an image-to-poem pipeline to generate corresponding poems and use a state-of-the-art image aesthetic evaluation model to assign an aesthetic score for each image.

Methods

Data

As for the convergence of language models, we need both plain texts and aesthetic texts. For simplicity, we reuse this text-image dataset, which is also used in Huh et al.'s paper[3], and then add another poem dataset.

Plain Text

We use the minhuh/prh dataset and use the wit_1024 revision, aligning the original paper. While the dataset is sampled from multilingual Wikipedia, due to English text dominating, we found that almost all the data is in English.

Poems

For poems, we use the Poems dataset from Kaggle. We find this dataset ideal for this project because of the following reasons:

- As the plain-text dataset contains 1,024 entries, it provides enough poems to yield a substantial amount of data.

- It categorizes the poems into 135 types based on their form (haiku, sonnet, etc.), which could facilitate our further studies.

Cleaning

Despite the high quality of this dataset, this dataset still needs to be cleaned before usage. We identify two problems with the raw dataset. First, some poems contain copyright notices at the end, which introduce noise into subsequent processing. However, because the copyright information is clearly marked with a special mark ©️, it can be easily removed through rule-based filtering. Second, although most poems are in English, a small portion is not. Since the plain-text dataset contains almost exclusively English texts, we should also remove the non-English poems from this dataset.

Afterward is an unknown term in future Before that we face the present, Coming at well future depends on present; Dismissing hazardous future Endeavor best early at present. Copyright © Muzahidul Reza | 29 November,2017

The text above shows an example of poems with copyright information. We assume that the mark © does not appear within the poem itself and remove all the content starting from any line that begins with this symbol.

To filter out non-English poems, we use the word frequency list as an auxiliary resource and construct an English lexicon by selecting only the words whose frequencies exceed a certain threshold (10,000). For each poem, we compute the proportion of lemmatized words that appear in this lexicon and apply a threshold to identify English poems. We initially experimented with this English words list, but it was overly inclusive and contained many non-English words such as bonjour. This caused some non-English poems to match a large number of dictionary entries. Therefore, we adopted a frequency-based filtering approach to exclude words that may have been borrowed from other languages and appear in English text only occasionally, despite being included in comprehensive dictionaries. The table shows how poems with different proportions of English words detected look like. To minimize bias while filtering out as much non-English data as possible, we chose a threshold of 0.8.

| Proportion | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 1.00 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poem | आज अपने ही खटकने लग गए रिश्ते नाज़ुक थे चटकने लग गए रास्तों की मुश्किलें हल हो गईं आके मंज़िल पर भटकने लग गए क्या कभी पहले भी ऐसा था हुआ ... |

illusionary

triskaidekaphobia's unaccountab le |

Nazakat husn se mashroot hoti gar zamane main.

To ye muflis pre paker na bikte aane aane main. |

Woyese to hum mile na kahin, ajnabi se they, Rishte na jane kaise kahan ke kabhi ke they. Dekha jo unko aankhon ne chupke se keya kaha, Alam ajeeb dil pe mere bebasi ke they. Majboor kar ke jane kahan ja ke chup gaye, ... |

Nu scylun hergan hefaenricaes uard metudæs maecti end his modgidanc uerc uuldurfadur sue he uundra gihuaes eci dryctin or astelidæ he aerist scop aelda barnum ... |

Ne vous étonnez pas, objets sacrés et doux,

Si quelqu'air de tristesse obscurcit mon visage. Quand un savant crayon dessinait cette image J'attendais l'échafaud et je pensais à vous. |

ALLAS! my worthi maister honorable, This landes verray tresor and richesse! Deth by thy deth hath harme irreparable Unto us doon: hir vengeable duresse Despoiled hath this land of the swetnesse ... |

N-ew acrostic quatrain I-s brought in for the first time; C-ombination of these two forms K-eeps the beauty so sublime. Topic: Birthday of Nicole "Nick" Asuncion (March 20) ... |

(Queer In Quatrain) Now so near, Now so far, You and I are In what a queer! ... |

Promise Of A Child (Dramatic Monologue) March 31, 2020 Believe me my, tribe I'm your child I know your dream ... |

Aesthetic Rating

To experiment with the convergence of models on poems with varying aesthetic qualities within the dataset, we need to assign each poem a score reflecting its aesthetic quality. However, human rating can be labor-intensive. Therefore, given the alignment between large language models (LLMs) and human preferences [4], we employed a large model to evaluate the aesthetic quality of poems. To avoid introducing bias and to balance model performance with the annotation consensus in the research community, we used the closed-source GPT-4o model, ensuring that it would not be used for testing alignment in subsequent experiments (in fact, only open-source models were used for later experiments). Our aesthetic scores follow a 5-point scale similar to a Likert scale. Inspired by the Chain of Thought (CoT)[5], we asked the model to output a paragraph of thinking to imitate humans' close reading rating process. The prompt used is shown below. We also conducted human evaluation tests to verify the consistency between the model's assessments and human preferences.

You are an objective literary evaluator.

Task:

1) Evaluate the beauty of the following poem and give it an integer score from 1 to 5 (1 = not beautiful, 5 = extremely beautiful).

2) First output a concise, non-sensitive rationale (a clear summary explaining why you gave this score). This should be at most ~200 words, avoid step-by-step internal chain-of-thought.

3) Then output the score.

4) Finally return a JSON object EXACTLY in this format (no extra commentary):

{{ "thinking": "<the concise rationale as a string>", "score": <int 1-5> }}

Poem to evaluate:

<poem_text>

Scoring criteria (you MUST apply these; briefly mention which criteria influenced the score in the rationale):

- Imagery & Sensory Detail (weight 30%): quality and vividness of images, sensory language.

- Emotional Impact (weight 25%): emotional resonance, ability to move reader.

- Language & Diction (weight 15%): word choice, originality, metaphors, semantic richness.

- Structure & Rhythm (weight 15%): line breaks, meter/flow, internal cohesion.

- Originality & Depth (weight 15%): fresh perspective or depth of thought.

Scoring method: evaluate each criterion on 0-10, compute weighted sum, map to 1-5:

total_score_0_10 = weighted average (0-10)

final_score = round(total_score_0_10 / 2) # maps 0-10 to 0-5, round to nearest int, but clamp to 1-5

Important instructions for your output:

- Do NOT reveal internal chain-of-thought. Only provide a concise rationale (summary) explaining which criteria mattered and how.

- Output MUST be valid JSON as specified in step 4. 'thinking' must be a string, 'score' an integer.

- Example of allowed rationale: "Strong imagery and emotional resonance; language sometimes cliché; good rhythm; overall score 4."

Now perform the evaluation.

After completing the annotation of the dataset, we have uploaded it to Hugging Face and made it publicly available for future use. The table below presents one example poem for each aesthetic score. As can be observed, although the scores correlate to some extent with the aesthetic quality of the text, the evaluation inevitably introduces additional biases, such as poem length or the rarity of vocabulary. We also address these factors in our experiments.

| Score | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poem | Everyone standing leaning by the side of a ditch. | Succeed success Be successful, Be happy earning peace Life is beautiful. |

When Gabby Hayes is more than name, When clean public rest rooms are not academic When honor over victory is no longer the province of party When you see the miracle of movement of every limb When this list is growing. |

Carefree paper kites soar with childhood dreams Still in my mind a distant merriment, Echoes of our laughter and glee it seems Return with their lost mirth and enchantment. Kites flying so free with innocent whims ... |

Presiding over a formica counter, plastic Mother and Child magnetized to the top of an ancient register, the heady mix of smells from the open bins ... |

Image and Image-Poem Data

Data Source and Acquisition

In this part, we used another Image-Text dataset available on Hugging Face. The dataset is developed from a randomly sampled subset of this dataset also available on Hugging Face. It contains a collection of images, each accompanied by detailed descriptive captions in English. In our project, it is prepared for image-text alignment tasks and provides high-quality image-description pairs suitable for later exploratory multimodal research.

We used the complete dataset, which consists of about 1,000 image-text pairs. Each entry in the dataset includes:

- A photographic image covering diverse subjects (landscapes, people, activities, objects, etc.)

- A detailed English description of the image, typically 3-5 sentences in length, describing the visual content, atmosphere, and contextual elements

In our detailed processing method, the images were extracted from Hugging Face and saved locally in a structured directory, while the metadata (image filenames and their corresponding text descriptions) was organized into a CSV file for efficient processing. This organizational structure allows for systematic access to both visual and textual data during the poem generation pipeline.

Image-to-Poem Generation Process

Using the acquired image-text dataset as input, we generated poems for each image through a neural network-based pipeline. The pipeline is proposed in this paper[6]. This process transforms visual information into poetic language, creating a new layer of creative textual interpretation alongside the original descriptive captions.

For each images in the dataset, the following workflow was executed:

- Visual Feature Extraction: Each image was processed through a pre-trained VGG convolutional neural network to extract high-level visual features. These features capture semantic information about objects, scenes, colors, and compositional elements present in the image.

- Neural Poem Generation: The extracted visual features were fed into a specialized poem generation model. This model uses a sequence-to-sequence architecture to translate visual representations into poetic verses, attempting to capture not only the literal content of the image but also its emotional tone and aesthetic qualities.

- Output Collection: The generated poems were collected and stored alongside the original data, creating an enriched dataset with three components for each image:

- The original image file

- The original descriptive caption from the Image-Text dataset

- The newly generated poem produced by our model

The complete results were compiled into a CSV file containing all three data elements, enabling comparative analysis between factual descriptions (plain text) and poetic interpretations (poems) of the same visual content.

Image Aesthetic Scoring

Then we applied the ROC4MLLM method from the paper Regression Over Classification-Assessing Image Aesthetics via Multimodal Large Language Models [7] to assign aesthetic scores to each of the approximately 1,000 images. This approach uses independent score-representation tokens and a position token to model aesthetic assessment as a regression task, which finally outputs continuous numerical scores for images. Then we mapped the continuous score to a discrete 1–5 rating scale, ensuring that the presentation of results aligns with previous poetry aesthetics rating schemes. This evaluation provides structured aesthetic labels for subsequent poetic image quality analysis and multimodal creative assessment.

Final Processed Dataset

The final processed dataset provides a unique resource for studying different modes of image interpretation:

- Original Descriptions: Factual, detailed prose descriptions focusing on objective visual elements, scene composition, and literal content

- Generated Poems: Creative, condensed poetic expressions attempting to capture the essence, mood, and aesthetic qualities of the images in verse form

- Image Aesthetic Scores: Discrete aesthetic ratings providing an explicit and standardized measure of perceived visual quality, enabling quantitative analysis of aesthetic preference and its relationship with textual representations.

This tripartite representation allows for analysis of how visual aesthetics are perceived, quantified, and articulated across different representational forms, making the dataset valuable for later exploratory multimodal research.

Model Convergence on Poems

According to the Platonic Representation Hypothesis, the representation spaces of different models will gradually converge as the models' capabilities strengthen. Therefore, we first tested the validity of this hypothesis on a poetry dataset. In the experiment, we used a total of seven different models, which varied in their architecture and parameters. Their specific information is shown in the table below. The wide range of model choices ensures that our experimental results are more generalizable.

| Model | Parameters / Size | Developer / Publisher |

|---|---|---|

| Meta-Llama-3-8B | ~8B parameters, dense | Meta |

| Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.1 | ~7B parameters | Mistral AI |

| Gemma-7B | ~7B parameters | Google DeepMind |

| Gemma-2B | ~2B parameters | Google DeepMind |

| BLOOMZ-1b7 | ~1.7B parameters (fine-tuned from BLOOM family) | BigScience |

| OLMo-1B-hf | ~1B parameters | Allen Institute for AI |

| BLOOMZ-560m | ~560M parameters (small fine-tuned model) | BigScience |

We measure the convergence of LLMs by calculating Mutual kNN. We input a data point into the language model to obtain the language model's representation space. Thus, for the representations of any two language models on a certain dataset, we can measure the overlap of the k-nearest neighbors (kNN) of each point within the two representation spaces. The higher the degree of overlap, the more similar the representations of the two models are on that dataset. We measured the convergence of every pair of models on the poetry dataset. Excluding the trivial relationship where a model is completely identical to itself, we obtained a total of 42 pairs of convergence values, half of which are symmetric to the other half. The figure at the right shows the convergence between all models (Sorted by parameter size), which demonstrates a trend that the larger the model parameters, the better the mutual convergence.

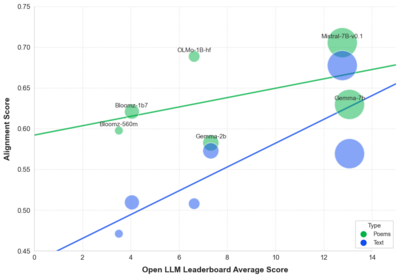

The number of parameters does not necessarily fully represent a model's capability. Therefore, we re-ranked the models based on the evaluation results (IFEval and Average) from the Open LLM Leaderboard. We then visualized the relationship between the capabilities of different models and their degree of alignment with Llama-3.1-8B, as shown in the figure below (where the size of the circle represents the parameter size. It is worth noting that OLMo-1B-hf, with only 1B parameters, has a capability almost only inferior to all the 7B models). The figure below also shows that as a model's capability gets stronger and closer to Llama-3.1-8B, its representation space convergence with Llama-3.1-8B also gets better.

The impact of aesthetic factors

In the previous experiments, we validated that the Platonic Representation Hypothesis still holds true for poetry data. Given this premise, we use a comparative experiment to investigate whether models exhibit different convergence capabilities for texts possessing different aesthetic qualities.

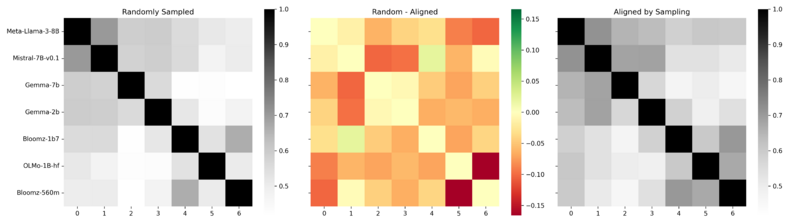

First, we compare poetry text and general descriptive text (plain text). We hypothesize that poetry is aesthetically superior, whereas our plain text contains descriptive captions for images, which are generally considered to lack aesthetic quality. We sampled the same amount of data from both datasets and measured the convergence scores for every pair among the seven models using the same experimental setting. The left and right panels of the figure below respectively show the models' convergence scores on the poetry and descriptive text, while the middle panel displays the difference between the poetry scores and the plain text scores. The results indicate that across all 21 model combinations, the model convergence on the poetry dataset is consistently higher than that on the plain descriptive text. We also plotted the correlation between the model's capability and the convergence scores.

Second, we compare the convergence of models between poems with different aesthetic scores. Although we used a 5-point scale for annotation, due to the limited number of samples at the extreme scores, we divided the data into only two sets based on the previously annotated aesthetic scores: one containing scores more than or equal to 4 and the other containing scores less than or equal to 3. We consider these two groups of poems to be more aesthetic and less aesthetic, respectively. The left and right panels of the figure below respectively show the models' convergence scores on the high-score and low-score poem subsets, while the middle panel displays the difference between the two. The results indicate the model convergence on the higher-scoring poetry dataset is not consistently higher than that on the lower-scoring one. However, there is still a significant pattern: the convergence between large-sized models is better on the high-score poems, while the convergence between small-sized models is better on the low-score poems. This may indicate a complex relationship between the model size and its convergence degree concerning aesthetic representation.

Third, the form. Similarly, due to the limitation of the dataset sample size, we cannot conduct experiments on a single specific type of poem. However, we can categorize poems into structured (such as Haiku, Sonnet, etc.) and free verse, based on whether they need to adhere to a certain format. Comparing the convergence of model representations on these two categories of poetry can, to some extent, investigate the influence of poetic form and type. The two categories are detailed below.

class FormatCategory:

FORMATED = ['burlesque', 'tetractys', 'villanelle', 'abecedarian', 'horatian-ode', 'bref-double', 'rhyme-royal / rime-royale', 'anacreontic', 'burns-stanza', 'bop', 'senryu', 'nonet', 'couplet', 'alexandrine', 'beymorlin-sonnet', 'monoku', 'divino-sonetto', 'limerick', 'sapphic', 'renga', 'acrostic', 'chain-verse', 'stanza', 'somonka', 'ballad', 'riddle', 'canzone', 'dactyl', 'pindaric-ode', 'triolet', 'ballade', 'tercet', 'terza-rima', 'brisbane-sonnet', 'blank-verse', 'haiku', 'shadorma', 'dirge', 'epithalamion', 'fourteener', 'arabian-sonnet', 'triversen', 'kyrielle', 'rictameter', 'choka', 'italian-sonnet', 'verse-paragraph', 'ode', 'busta-sonetto', 'octave', 'sijo', 'sonnet', 'glosa', 'curtal-sonnet', 'shi', 'quatern', 'elegy', 'dizain', 'catena-rondo', 'ottava-rima', 'ghazal', 'clerihew', 'rondeau', 'madrigal', 'spenserian-stanza', 'epigram', 'tyburn', 'balassi-stanza', 'pantoum', 'sestet', 'canzonetta', 'syllabic-verse', 'tanka', 'double-dactyl', 'cavatina', 'sestina', 'cinquain', 'quatrain', 'rondel / roundel', 'dramatic-monologue']

NONFORMATED = ['prose-poem', 'oulipo', 'abc', 'pastoral', 'kennings', 'panegyric', 'bio', 'slam', 'aubade', 'imagery', 'iambic-pentamerer', 'decastich', 'carol', 'ekphrastic', 'landays', 'carpe-diems', 'qasida', 'mock-epic', 'anagram', 'ars-poetica', 'palindrome', 'anaphora', 'lyric', 'lay', 'blues-poem', 'verse', 'conceit', 'narrative', 'cacophony', 'blank-verse', 'bucolic', 'collins-sestet', 'found-poem', 'irregular-ode', 'epic', 'cento', 'hymn', 'shi', 'elegy', 'occasional-poem', 'epistrophe', 'heroic-couplet', 'doggerel', 'palinode', 'free-verse', 'epistle', 'rispetto', 'echo-verse', 'didactic-poetry', 'lament', 'dramatic-monologue']

The left and right panels of the figure below respectively show the scores for structured poems and free verse poems, with the difference between the two in the middle. The results are similar to the previous findings: although there is no completely consistent pattern, a different pattern emerges between large and small models: large models exhibit better convergence on structured poems, while small models show the opposite.

Adjustment to reduce bias

Aligning lengths

The results from the previous section suggest that, although the model convergence on the poetry and plain text datasets shows strong consistency, there might be more complex mechanisms and reasons at play concerning more detailed aesthetic factors. To further investigate these mechanisms, it is necessary to apply a degree of correction to our models and naive methods to reduce the introduction of bias.

One relatively external factor is text length. We noted that, due to the inclusion of many long poems in the dataset and the generally verbose nature of most poems, the poetry dataset is noticeably longer than the plain text dataset.

Therefore, we compared short poems (shorter than the dataset median) and long poems (longer than or equal to the dataset median), as shown in the figure below. The results indicate that length is a factor that cannot be ignored, and thus its influence must be minimized in cross-dataset comparisons.

We used the length distribution of the Plain Text dataset as a baseline to sample from the Poem dataset, ensuring that the two sets of data have the same length distribution. The figure below shows the length distributions align well after sampling.

Handling sampling bias

After performing length-aligned sampling, our effective poetry data volume was significantly reduced. To ensure a fair comparison, we also need to sample the plain text data to make the quantities of the two datasets equal.

We noted that different types of data have obvious distinctions in the model's representation space. This distinction leads to differences in the ability of various data types to handle noise when applying the Mutual kNN algorithm (we conducted some discussion on whether this difference in representation space should be considered an intrinsic difference in the data or a bias introduced externally, and this is included in the Limitation section).

The figure below shows the visualization of the representation spaces of different data after dimensionality reduction using t-SNE[8]. It can be seen that poems with different lengths and different aesthetic scores have different distributions in the representation space (It is worth noting that, based on the visualization results of dimensionality reduction, texts with different aesthetic scores may be continuously distributed on a manifold according to their score magnitude).

Given the fact that poetry (short poems after length-aligned sampling) and plain text are vastly different, we performed a special sampling on the plain text to align their distributions. The specific method is as follows: First, both datasets are concatenated, standardized, and reduced in dimensions using PCA[9]. A logistic regression classifier is then trained to distinguish the small dataset from the large one. The predicted probabilities on the large dataset indicate how similar each point is to the small dataset and are used as sampling weights. Finally, samples are drawn from the large dataset according to these similarities, producing a subset of plain text that closely resembles the short poem set.

Results

After sampling, we conduct the experiments again on the sampled datasets, and the results are as follows.

We found that, compared to the original unadjusted version, the advantage of smaller models in converging on poetry data is more obvious here. Furthermore, the pattern that larger models show better convergence has, to some extent, become less obvious for these shorter aesthetic poems. We hypothesize that models can master these simple aesthetic factors relatively early in training. Therefore, even the convergence among smaller models can clearly benefit from an improvement in aesthetic quality (plain text to poems), leading us to infer that aesthetics is a relatively fundamental skill acquired early in model training.

Still, considering the combined conclusions above, such as the greater increase in convergence for small models when dealing with low-score poems (i.e., the convergence of small models drop rapidly as the text's aesthetic quality rises), and the more pronounced increase in convergence for small models when facing free verse, we believe these experiments point to a consistent tendency: the convergence among smaller models is more sensitive to an increase in aesthetic quality and simplification of the text (shorter length, fixed format) within poems, and smaller models are not capable of distinguish fine-grained aesthetic attributes.

Behind aesthetics: topics and rarity

In order to further reveal the role and mechanism of aesthetic factors in model learning and convergence, we hypothesized two factors that would simultaneously influence both aesthetic quality and the model's representation space: semantic features and rarity. We designed some experiments to conduct deeper research on these factors.

Semantics and Topics

We believe that poetry contains many conceptual features (or imageries), leading to a high degree of semantic similarity (as shown in the word cloud plot above). In contrast, the corresponding descriptive text lacks this similarity. We therefore modeled and compared the similarity of these texts.

| Dataset | Cosine Similarity |

|---|---|

| Plain Texts | 0.0970 |

| Poems | 0.1883 |

| Poems Cluster 1 | 0.2975 |

| Poems Cluster 2 | 0.1205 |

We used the small model with an encoder-only architecture, sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2 (which had not been used in other tasks to reduce bias), to map each text into a 384-dimensional dense vector, and used cosine similarity to measure the semantic distance. We then used K-means clustering to divide the poetry dataset into two subsets.

The table on the right shows the average semantic similarity for the plain text, the poetry dataset, and the two cluster subsets. Indeed, the average semantic distance between descriptive texts is larger than that of poems. The word clouds of the two clusters of poems are shown below.

After adjusting and controlling for an equal number of samples in the full poetry dataset and the two subsets, we measured the model convergence on these subsets. The figure below compares the alignment scores of the other six models with Meta-Llama-3-8B (sorted by model capability).

It can be seen from the trends that a pattern divergence still exists between large and small models (where the dividing line separates models below 3B, which struggle to show scaling improvement, and 7B models, which exhibit scalability due to the scaling law), and the trend lines intersect at one point.

Overall, the alignment is lower between semantically similar data. This can be interpreted as semantically similar datasets being more intertwined and harder to distinguish. However, this is contrary to the convergence difference observed between poetry and descriptive text, where semantically similar poetry shows better convergence. Therefore, semantic distance cannot fully explain the model's convergence behavior on poetry.

The figure still reveals the distinction between models, and smaller models exhibit a greater difference in scores between the two clusters. This further supports the previous hypothesis: that smaller models have greater difficulty distinguishing the fine-grained aesthetic differences within the poetry dataset.

Rarity

Rarity refers to the frequency of similar texts appearing during the model's training process. The rarer the data, the less it is exposed during model training, making it harder to train and more difficult for smaller models to master. The rarity of a text to a model can be roughly estimated using perplexity[10]. This is because perplexity reflects how surprised a model is when predicting a sequence. If the model has seen similar patterns many times, it assigns high confidence and yields low perplexity. Conversely, if the sequence is unfamiliar or underrepresented in training data, the model's predictions become uncertain, resulting in higher perplexity. Thus, perplexity serves as an indirect but practical indicator of how rare a text is relative to the model’s training distribution. To measure the perplexities of our data, we use another model that has not been used before to ensure fairness. For simplicity, we use GPT-2.

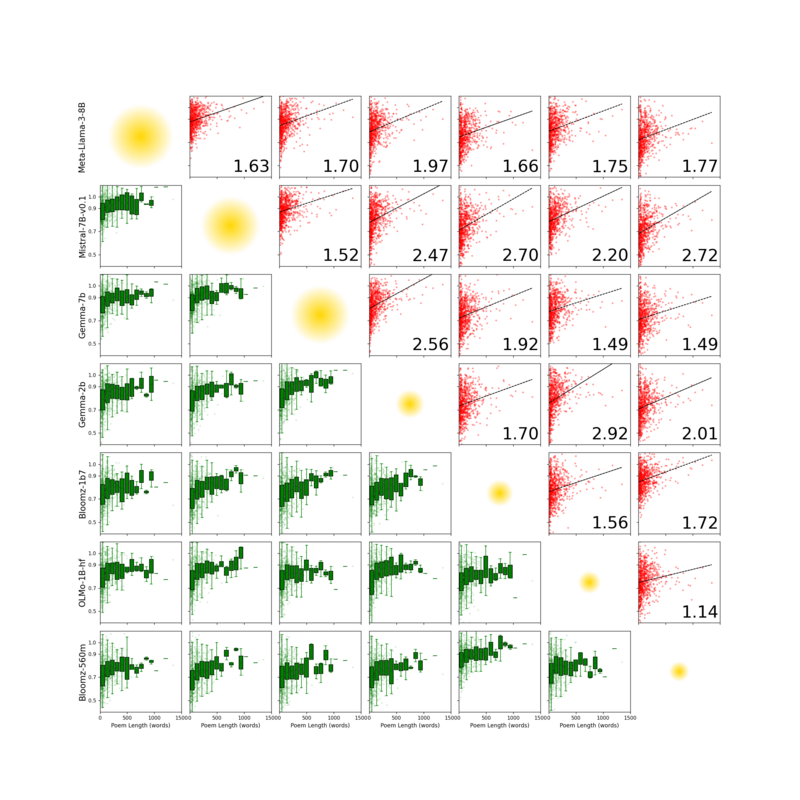

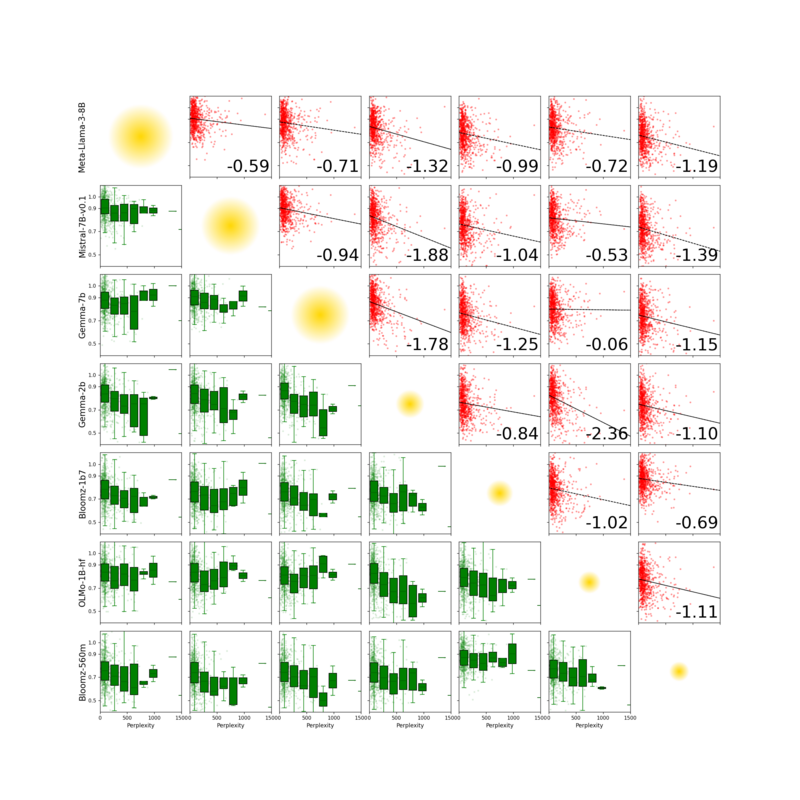

Since we need to examine the relationship between the rarity of each individual data point and the corresponding uniformity (or alignment) between models for that data point, we obtained the alignment for every data point across the 21 model pairs before averaging across all data. We first used the length relationship (where a consistent positive correlation between length and inter-model alignment was established in previous experiments) to validate our method, and the results are shown below.

The figure is divided into 49 grids (including diagnostic empty grids), where the models are sorted by parameter size from top to bottom and left to right. Each corresponding grid shows the relationship between the length of individual data points and the alignment score for a specific pair of models (since the alignment score for a single data point can only be an integer multiple of 1/topk, we added Gaussian noise with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 0.5 to simulate a scatter plot). The bottom-left part displays the quantile plots, and the top-right part (symmetric to the bottom-left) shows the linear fit results and the slope. It can be observed that for every pair of models, the data length is positively correlated with the data alignment, which is consistent with the previous conclusion.

The results regarding perplexities are as follows. We can observe that, contrary to length, perplexity is negatively correlated with the degree of model convergence, meaning that the rarer the data, the worse its convergence, which aligns with intuition. Therefore, to study the relationship between rarity and aesthetic score, we also plotted the relationship between the aesthetic annotation score and perplexity, as shown in the figure on the right.

Contrary to intuition, poetry, which is hypothesized to have a higher aesthetic quality, actually exhibits lower perplexity, meaning the model is more familiar with it, or it is not rare in the training process. Furthermore, the relationship between perplexity and the aesthetic score of the poems (with Gaussian noise added) shown in the figure below also indicates that higher aesthetic quality corresponds to lower perplexity. In other words, texts with high aesthetic qualities are basic, not rare, in model training. Regardless of the deviation from intuition, to some extent, it explains the previous conclusion: texts with a certain aesthetic quality are easier to train because they are not rare during model training, and thus aesthetic skills are more likely to be acquired by the model early on.

Multimodal Convergence

In this part, we make use of our Image-Description-Poem dataset to explore the convergence between language models and vision models. To this end, we also select 7 Vision Transformer (ViT) Models with different parameter sizes and training methods. The vision models are listed below:

| Model Name | Architecture Size | Patch Size | Input Resolution | Pre-training Task / Method | Pre-training Dataset | Approx. Parameters (Params) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vit_tiny_patch16_224.augreg_in21k | Tiny (T) | 16x16 | 224x224 | AugReg / Weakly Supervised | ImageNet-21k | 5.7M |

| vit_small_patch16_224.augreg_in21k | Small (S) | 16x16 | 224x224 | AugReg / Weakly Supervised | ImageNet-21k | 22M |

| vit_base_patch16_224.mae | Base (B) | 16x16 | 224x224 | Masked Autoencoders (MAE) / Self-supervised Learning | ImageNet-1K / 21K | 86M |

| vit_base_patch14_dinov2.lvd142m | Base (B) | 14x14 | 224x224 | DINOv2 / Self-supervised Learning | LVD-142M | 86M |

| vit_large_patch14_dinov2.lvd142m | Large (L) | 14x14 | 224x224 | DINOv2 / Self-supervised Learning | LVD-142M | 307M |

| vit_large_patch14_clip_224.laion2b | Large (L) | 14x14 | 224x224 | CLIP / Image-Text Contrastive Learning | LAION-2B | 307M |

| vit_huge_patch14_clip_224.laion2b_ft_in12k | Huge (H) | 14x14 | 224x224 | CLIP / Image-Text Contrastive Learning (Fine-tuned on IN-12K) | LAION-2B | 632M |

We still compare the convergence of language and vision models using mutual knn, and we set tok=10. As we have 7 language models and 7 vision models, we use a heatmap with 7*7=49 grids to show the results. Note that this time the heatmap is no longer symmetric, as the grid (i,j) is the convergence of the language model i and the vision model j, while grid (j,i) represents the convergence of the language model j and the vision model i. Also, the diagonal values are not 1.

We use different scales to show the figures, so the same color for different figures does not represent the same value. We can notice that the convergence on Image-Poem Pairs is much smaller than that of Image-Text Pairs. This huge gap cannot be explained by the aesthetic level, but by the huge semantic disimilarity of the poems and the images. However, we can notice that, for Image-Poems or Image-Texts, the trends are still there - larger models tend to converge better, except for an outlier: Gemma-2b. Gemma-2b shows an extremely low convergence with all the ViTs we used, and it is not observed either in the model from the same company (Gemma-7b) or from a similar small model with a similar parameter size (BLOOMZ-1b7).

We find it impossible to derive any aesthetic-wise conclusion by comparing the convergence of Image-Poem Pairs and Image-Text Pairs, as the semantic gap always exists. However, we can compare the convergence between models on images of different aesthetic levels. We saved the convergence score for each point and compared the convergence scores when the image scores were 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively. Since we have a total of 49 model pairs/combinations, we placed the data for each pair in a grid. Below are the results on the Image-Text Pairs.

In the figure, the purple grid means the convergence increases when the aesthetic level of images increases. The darker a grid is, the more obvious the trend is. Yellow grids mean the opposite trend. We can conclude that the convergence score is positively correlated to the aesthetic score of images, meaning models converge better on beautiful images.

The figure below shows the results on Image-Poem Pairs.

The conclusion that the models converge better on beautiful images still generally holds true, but is weakened for Image-Poem Pairs. It is debatable whether the trends is influenced because the poems here do not really semantically represent the images. Another observation is the opposite trends are always found for large-small or small-small model pairs, which can strengthen, to some extent, that the small models struggle to distinguish fine-grained aesthetic levels.

Conclusion

Summarizing the results above, based on our experimental findings and interpretation, we have the following potential takeaways:

- Models share a sense of beauty, to some extent.

- Convergence on aesthetic texts is not evidence of a sophisticated, human-like artistic sense. Instead, it reveals that what we consider aesthetic are fundamental features of language that models master early in their training.

- What truly distinguishes smaller models from more capable large models is the fine-grained differentiation and perception of aesthetic quality. In this regard, smaller models struggle, while larger models have a better success chance. It happens both between language models and vision-language models, revealing that it could be a universal trend for models with different modalities.

Quality Assessment and Limitations

Justification of Sampling

We mentioned that the length-sampled poetry dataset and the original descriptive text dataset exhibit different distributions in the representation space of the same model, and this difference in distribution affects the calculation results of Mutual kNN. However, we obtained divergent views on whether this distribution difference should be controlled in the experiment:

- The first perspective considers that this distribution difference is caused by the intrinsic difference between aesthetic and non-aesthetic texts, which is a fundamental distinction between the two types of text. Consequently, eliminating this distribution difference would, to a certain extent, weaken the aesthetic distinction between the two types of text.

- The second perspective holds that this distribution difference is an external dataset feature. This distribution does indeed interfere with the calculation of results due to external factors: due to noise in the training set or the imperfect degree of training, the model's representation for each sentence cannot be placed perfectly at its ideal position, so every sentence contains a certain amount of noise. However, under such noisy conditions, the more tightly distributed the points, the more easily their nearest neighbors are disturbed, and the greater the difference in Mutual kNN. This is also true for other metrics. Therefore, sampling subsets with similar distributions within their respective datasets can reduce this discrepancy to some extent.

Looking at the experimental results, the plain text sampled according to the poetry data actually showed worse convergence, which contradicts the result of the first perspective. The second perspective can explain this difference: the sampled texts became denser, and the alignment score would be reduced to a greater extent. We ultimately believe that only a portion of this distribution difference arises from the intrinsic attributes of aesthetic and non-aesthetic texts, while the other portion comes from other data attributes, leading to an excessive introduction of external bias.

Limitations

- Our aesthetic scoring process was conducted using the closed-source model GPT-4o. Although GPT-4o has demonstrated a strong ability to align with human preferences, its scores will still introduce a certain degree of bias. In particular, the model might assign higher scores to texts it is more familiar with, potentially pre-introducing the observed pattern where higher aesthetic quality corresponds to lower perplexity. Completely eliminating this bias would require extensive human annotation and consistency checks, but aesthetic quality is also a difficult abstract measure to precisely quantify. Therefore, even if the time and labor cost of manual annotation were overcome, it would be difficult to achieve this beforehand.

- Limited by computational resources, we were unable to use models larger than 8B. While our experiments can explain the different patterns between small and large models to some extent, we do not know if this pattern will persist with even larger models. The 7B model has become a benchmark for demonstrating the Scaling Law, but this is only the lower limit of the benchmark. To reveal the patterns of larger models, models such as 32B and 70B would need to be considered, which is unaffordable under our current experimental setup.

- Mutual kNN cannot fully achieve cross-dataset comparison because the model's representation spaces inherently differ across different datasets. The noise introduced during model training has a relatively larger impact in denser representation spaces. Trying to eliminate these differences in representation spaces can easily introduce other biases (such as changing the average length of the data). Controlling more variables would drastically reduce the amount of usable data in our dataset, which is also unrealistic. Therefore, after attempting to decouple length and align the representation spaces, we are unable to further eliminate other biases.

- The variety and quantity of our datasets could still be improved. Poetry is not the only form of aesthetic text, and using a larger quantity of both poetry and descriptive texts could make the conclusions more solid. However, expanding the dataset would also increase the cost of annotation and the time cost for model computation. Thus, we did not use a very large amount of data for the experiments, annotating and using only 800 poems and 1024 descriptive texts.

- Regarding cross-modal convergence between image and text, our experiments remain exploratory. The poems in our dataset were derived from image generation techniques based on older literature, limiting the expected generation quality. The vision-language models were not explicitly trained on poetry, and the poems have a large semantic distance from the corresponding images. This prevents a fair comparison with descriptive text to isolate differences that are not attributed to aesthetic factors. While comparing poems across different semantic distances and extrapolating to a 'hypothetical zero semantic difference point' could be attempted, it would necessitate substantial dataset resources.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Anna Karenina principle, Wikipedia

- ↑ K-means clustering, Wikipedia

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Huh, M., Cheung, B., Wang, T., Isola, P. (2024). The Platonic representation hypothesis. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.07987

- ↑ Bai, Y., Jones, A., Ndousse, K., Askell, A., Chen, A., DasSarma, N., Drain, D., Fort, S., Ganguli, D., Henighan, T., Joseph, N., Kadavath, S., Kernion, J., Conerly, T., El-Showk, S., Elhage, N., Hatfield-Dodds, Z., Hernandez, D., Hume, T., … Kaplan, J. (2022). Training a helpful and harmless assistant with reinforcement learning from human feedback. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2204.05862

- ↑ Chain of Thought (CoT), Wikipedia

- ↑ Liu, B., Fu, J., Kato, M. P., Yoshikawa, M. (2018). Beyond Narrative Description: Generating Poetry from Images by Multi-Adversarial Training. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.08473

- ↑ Ma, X., He, S., Ming, A., Zhong, H., Ma, H. (2026). Regression over classification: Assessing image aesthetics via multimodal large language models. In Proceedings of the 40th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI).

- ↑ t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding, Wikipedia

- ↑ Principal component analysis, Wikipedia

- ↑ Perplexity, Wikipedia

Credits

Course: Foundation of Digital Humanities (DH-405), EPFL

Professor: Frédéric Kaplan

Supervisors: Alexander Rusnak

Authors: Jiajun Shen, Yifan Zhou, Yibo Yin